Albuminuria: When urine predicts kidney and cardiovascular disease

ABSTRACTAlbuminuria is common. Traditionally considered a precursor to diabetic nephropathy, it has now been directly linked to adverse cardiovascular outcomes and death, independent of other risk factors. In this review, we compare the measures of albuminuria, examine the evidence linking it to renal failure, cardiovascular disease, and death, and provide recommendations for its testing and management.

KEY POINTS

- Albuminuria is best measured by the albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

- In several studies, albuminuria has been independently associated with a higher risk of death, cardiovascular events, heart failure, stroke, and progression of chronic kidney disease.

- Despite strong evidence linking albuminuria to adverse outcomes, evidence is limited in favor of routinely screening for it in the general population.

- Evaluating and managing albuminuria require understanding the limits of its clinical measures, controlling other risk factors for progression of renal disease, managing it medically, and referring to a specialist in certain situations.

RENAL COMPLICATIONS OF ALBUMINURIA

A failure of the glomerular filtration barrier or of proximal tubular reabsorption accounts for most cases of pathologic albuminuria.16 Processes affecting the glomerular filtration of albumin include endothelial cell dysfunction and abnormalities with the glomerular basement membrane, podocytes, or the slit diaphragms among the podocytic processes.17

Ultrafiltrated albumin has been directly implicated in tubulointerstitial damage and glomerulosclerosis through diverse pathways. In the proximal tubule, albumin up-regulates interleukin 8 (a chemoattractant for lymphocytes and neutrophils), induces synthesis of endothelin 1 (which stimulates renal cell proliferation, extracellular matrix production, and monocyte attraction), and causes apoptosis of tubular cells.18 In response to albumin, proximal tubular cells also stimulate interstitial fibroblasts via paracrine release of transforming growth factor beta, either directly or by activating complement or macrophages.18,19

Studies linking albuminuria to kidney disease

Albuminuria has traditionally been associated with diabetes mellitus as a predictor of overt diabetic nephropathy,20,21 although in type 1 diabetes, established albuminuria can spontaneously regress.22

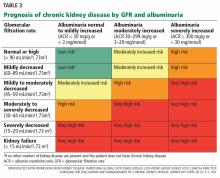

Albuminuria is also a strong predictor of progression in chronic kidney disease.23 In fact, in the last decade, albuminuria has become an independent criterion in the definition of chronic kidney disease; excretion of more than 30 mg of albumin per day, sustained for at least 3 months, qualifies as chronic kidney disease, with independent prognostic implications (Table 3).13

Astor et al,24 in a meta-analysis of 13 studies with more than 21,000 patients with chronic kidney disease, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease was three times higher in those with albuminuria.

Gansevoort et al,23 in a meta-analysis of nine studies with nearly 850,000 participants from the general population, found that the risk of end-stage renal disease increased continuously as albumin excretion increased. They also found that as albuminuria increased, so did the risk of progression of chronic kidney disease and the incidence of acute kidney injury.

Hemmelgarn et al,25 in a large pooled cohort study with more than 1.5 million participants from the general population, showed that increasing albuminuria was associated with a decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and with progression to end-stage renal disease across all strata of baseline renal function. For example, in persons with an estimated GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

- 1 per 1,000 person-years for those with no proteinuria

- 2.8 per 1,000 person-years for those with mild proteinuria (trace or 1+ by dipstick or ACR 30–300 mg/g)

- 13.4 per 1,000 person-years for those with heavy proteinuria (2+ or ACR > 300 mg/g).

Rates of progression to end-stage renal disease were:

- 0.03 per 1,000 person-years with no proteinuria

- 0.05 per 1,000 person-years with mild proteinuria

- 1 per 1,000 person-years with heavy proteinuria.25

CARDIOVASCULAR CONSEQUENCES OF ALBUMINURIA

The exact pathophysiologic link between albuminuria and cardiovascular disease is unknown, but several mechanisms have been proposed.

One is that generalized endothelial dysfunction causes both albuminuria and cardiovascular disease.26 Endothelium-derived nitric oxide has vasodilator, antiplatelet, antiproliferative, antiadhesive, permeability-decreasing, and anti-inflammatory properties. Impaired endothelial synthesis of nitric oxide has been independently associated with both microalbuminuria and diabetes.27

Low levels of heparan sulfate (which has antithrombogenic effects and decreases vessel permeability) in the glycocalyx lining vessel walls may also account for albuminuria and for the other cardiovascular effects.28–30 These changes may be the consequence of chronic low-grade inflammation, which precedes the occurrence and progression of both albuminuria and atherothrombotic disease. The resulting abnormalities in the endothelial glycocalyx could lead to increased glomerular permeability to albumin and may also be implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.26

In an atherosclerotic aorta and coronary arteries, the endothelial dysfunction may cause increased leakage of cholesterol and glycated end-products into the myocardium, resulting in increasing wall stiffness and left ventricular mass. A similar atherosclerotic process may account for coronary artery microthrombi, resulting in subendocardial ischemia that could lead to systolic and diastolic heart dysfunction.31

Studies linking albuminuria to heart disease

There is convincing evidence that albuminuria is associated with cardiovascular disease. An ACR between 30 and 300 mg/g was independently associated with myocardial infarction and ischemia.32 People with albuminuria have more than twice the risk of severe coronary artery disease, and albuminuria is also associated with increased intimal thickening in the carotid arteries.33,34 An ACR in the same range has been associated with increased incidence and progression of coronary artery calcification.35 Higher brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity has also been demonstrated with albuminuria in a dose-dependent fashion.36,37

An ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g has been linked to left ventricular hypertrophy independently of other risk factors,38 and functionally with diastolic dysfunction and abnormal midwall shortening.39 In a study of a subgroup of patients with diabetes from a population-based cohort of Native American patients (the Strong Heart Study),39 the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction was:

- 16% in those with no albuminuria

- 26% in those with an ACR of 30 to 300 mg/g

- 31% in those with an ACR greater than 300 mg/g.

The association persisted even after controlling for age, sex, hypertension, and other covariates.

Those pathologic associations have been directly linked to clinical outcomes. For patients with heart failure (New York Heart Association class II–IV), a study found that albuminuria (an ACR > 30 mg/g) conferred a 41% higher risk of admission for heart failure, and an ACR greater than 300 mg/g was associated with an 88% higher risk.40

In an analysis of a prospective cohort from the general population with albuminuria and a low prevalence of renal dysfunction (the Prevention of Renal and Vascular Endstage Disease study),41 albuminuria was associated with a modest increase in the incidence of the composite end point of myocardial infarction, stroke, ischemic heart disease, revascularization procedures, and all-cause mortality per doubling of the urine albumin excretion (hazard ratio 1.08, range 1.04 –1.12).

The relationship to cardiovascular outcomes extends below traditional lower-limit thresholds of albuminuria (corresponding to an ACR > 30 mg/g). A subgroup of patients from the Framingham Offspring Study without prevalent cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, or kidney disease, and thus with a low to intermediate probability of cardiovascular events, were found to have thresholds for albuminuria as low as 5.3 mg/g in men and 10.8 mg/g in women to discriminate between incident coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, other peripheral vascular disease, or death.42

In a meta-analysis including more than 1 million patients in the general population, increasing albuminuria was associated with an increase in deaths from all causes in a continuous manner, with no threshold effect.43 In patients with an ACR of 30 mg/g, the hazard ratio for death was 1.63, increasing to 2.22 for those with more than 300 mg/g compared with those with no albuminuria. A similar increase in the risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, or sudden cardiac death was noted with higher ACR.43

Important prospective cohort studies and meta-analyses related to albuminuria and kidney and cardiovascular disease and death are summarized in the eTable.23,39–50