Transient ischemic attack: Omen and opportunity

ABSTRACTA transient ischemic attack (TIA) is not a benign event; it is often the precursor of stroke. As such, every TIA deserves to be taken seriously, and patients who present with a TIA should be promptly evaluated and, if appropriate, started on stroke-preventive therapy.

KEY POINTS

- Modifiable risk factors for stroke and TIA include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, lipid abnormalities, atrial fibrillation, carotid stenosis, and dietary and hormonal factors.

- The three major mechanisms of stroke and TIA are thrombosis, embolism, and decreased systemic perfusion.

- Typical symptoms of TIA include hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, aphasia, vision loss, ataxia, and diplopia. Three clinical features that suggest TIA are rapid onset of symptoms, no history of similar episodes in the past, and the absence of nonspecific symptoms.

- In suspected TIA, magnetic resonance imaging is clearly superior to noncontrast computed tomography (CT) for detecting small areas of ischemia; this test should be used unless contraindicated.

- Imaging studies of the blood vessels include CT angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, conventional angiography, and extracranial and transcranial ultrasonography.

A transient ischemic attack (TIA), like an episode of unstable angina, is an ominous portent of future morbidity and death even though, by definition, the event leaves no residual neurologic deficit.

But there is a positive side. When a patient presents with a TIA, the physician has the rare opportunity to reduce the risk of a disabling outcome—in this case, stroke. Therefore, patients deserve a rapid and thorough evaluation and appropriate stroke-preventive treatment.

MANY ‘TIAs’ ARE ACTUALLY STROKES

TIA has traditionally been described as a sudden focal neurologic deficit that lasts less than 24 hours, is presumed to be of vascular origin, and is confined to an area of the brain, spinal cord, or eye perfused by a specific artery. This symptom-based definition was based on the arbitrary and inaccurate assumption that brief symptoms would not be associated with damage to brain parenchyma.

The definition has since been updated and made more rational based on new concepts of brain ischemia informed by imaging, especially diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1 One-third of episodes characterized as a TIA according to the classic definition would be considered an infarction on the basis of diffusion-weighted MRI.2 The new tissue-based definition characterizes TIA as a brief episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal ischemia of the brain, spinal cord, or retina, with clinical symptoms lasting less than 24 hours and without evidence of acute infarction.3

AN OPPORTUNITY TO INTERVENE

Most TIAs resolve in less than 30 minutes. The US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke trial of tissue plasminogen activator found that if symptoms of cerebral ischemia had not resolved by 1 hour or had not rapidly improved within 3 hours, complete resolution was rare (only 2% at 24 hours).4 Hence, physicians evaluating and treating patients with TIAs should treat these episodes with the urgency they deserve.

Moreover, half of the strokes that follow TIAs occur within 48 hours.5 A rapid and thorough evaluation and the initiation of secondary preventive treatments have been shown to reduce the early occurrence of stroke by up to 80%.6 Hence, the correct diagnosis of TIA gives the clinician the best opportunity to prevent stroke and its personal, social, and sometimes fatal consequences.

STROKES OUTNUMBER TIAs, BUT TIAs ARE UNDERREPORTED

According to 2012 statistics, nearly 795,000 strokes occur in the United States each year, 610,000 of which are first attacks and 185,000 are recurrences. Every 40 seconds, someone in the United States has a stroke.7

In comparison, the incidence of TIA in the United States is estimated at 200,000 to 500,000 per year, though the true number is difficult to know because of underreporting.8,9 About half of patients who experience a TIA fail to report it to their health care provider—a lost opportunity for intervention and stroke prevention.10,11

A meta-analysis showed that the risk of stroke after TIA was 9.9% at 2 days, 13.4% at 30 days, and 17.3% at 90 days.12

Interestingly, the risk of stroke after TIA exceeds the risk of recurrent stroke after a first stroke. This was shown in a study that found that patients who had made a substantial recovery within 24 hours (ie, patients with a TIA) were more likely to suffer neurologic deterioration in the next 3 months than were those who did not have significant early improvement.13

RISK FACTORS FOR TIA ARE THE SAME AS FOR STROKE

The risk of cerebrovascular disease increases with age and is higher in men14 and in blacks and Hispanics.15

The risk factors and clinical presentation do not differ between TIA and stroke, so the evaluation and treatment should not differ either. These two events represent a continuum of the same disease entity.

Some risk factors for TIA are modifiable, others are not.

Nonmodifiable risk factors

Nonmodifiable risk factors for TIA include older age, male sex, African American race, low birth weight, Hispanic ethnicity, and family history. If the patient has nonmodifiable risk factors, we should try all the harder to correct the modifiable ones.

Older age. The risk of ischemic stroke and intracranial hemorrhage doubles with each decade after age 55 in both sexes.16

Sex. Men have a significantly higher incidence of TIA than women,11 whereas the opposite is true for stroke: women have a higher lifetime risk of stroke than men.17

African Americans have an incidence of stroke (all types) 38% higher than that of whites,18 and an incidence of TIA (inpatient and out-of-hospital) 40% higher than the overall age- and sex-adjusted rate in the white population.11

Low birth weight. The odds of stroke are more than twice as high in people who weighed less than 2,500 g at birth compared with those who weighed 4,000 g or more, probably because of a correlation between low birth weight and hypertension.19

A family history of stroke increases the risk of stroke by nearly 30%, the association being stronger with large-vessel and smallvessel stroke than with cardioembolic stroke.20

Modifiable risk factors

Modifiable risk factors include cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes, lipid abnormalities, atrial fibrillation, carotid stenosis, and dietary and hormonal factors. Detecting these factors, which often coexist, is the first step in trying to modify them and reduce the patient’s risk.

Cigarette smoking approximately doubles the risk of ischemic stroke.21–23

Hypertension has a relationship with stroke risk that is strong, continuous, graded, consistent, and significant.24

Diabetes increases stroke risk nearly six times.25

Lipid abnormalities. Most studies have found an association between lipid levels (total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and the risk of death from ischemic stroke,26–28 and an inverse relationship between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and stroke risk.29

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of ischemic stroke up to fivefold, even in the absence of cardiac valvular disease. The mechanism is embolism of stasis-induced thrombi that form in the left atrial appendage.30

Carotid stenosis. Asymptomatic carotid atherosclerotic stenotic lesions in the extracranial internal carotid artery or carotid bulb are associated with a higher risk of stroke.24,31

Lifestyle factors. Diets that lower blood pressure have been found to decrease stroke risk.24 Exercise in men and women reduces the risk of stroke or death by 25% to 30% compared with inactive people.32 Weight reduction has been found to lower blood pressure and reduce stroke risk.24

Other potentially modifiable risk factors include migraine with aura, metabolic syndrome, excess alcohol consumption (and, paradoxically, complete abstinence from alcohol), drug abuse, sleep-disordered breathing, hyperhomocysteinemia, high lipoprotein (a) levels, hypercoagulability, infection with organisms such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, and Helicobacter pylori, and acute infections such as respiratory and urinary infections.26

Conditions in certain demographic groups

Patients in certain demographic groups present with rarer conditions associated with stroke and TIA.

Sickle cell disease. Eleven percent of patients with sickle cell disease have clinical strokes, and a substantial number have “silent” infarcts identified on neuroimaging.33,34

Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy with any product containing conjugated equine estrogen carries a risk of cerebrovascular events,35 and the higher the dose, the higher the risk.36 Also, oral contraceptives may be harmful in women who have additional risk factors such as cigarette smoking, prior thromboembolic events, or migraine with aura.37,38

THREE CAUSES OF STROKE AND TIA

Stroke and TIA should not be considered diagnoses in themselves, but rather the end point of many other diseases. The diagnosis lies in identifying the mechanism of the cerebrovascular event. The three main mechanisms are thrombosis, embolism, and decreased perfusion.

Thrombosis is caused by obstruction of blood flow within one or more blood vessels, the most common cause being atherosclerosis. Large-artery atherosclerosis, such as in the carotid bifurcation or extracranial internal carotid, causes TIAs that occur over a period of weeks or months with a variety of presentations in that vascular territory, from years of gradual accumulation of atherosclerotic plaque.39

In patients with small-artery or penetrating artery disease, hypertension is the primary risk factor and the pathology, specific to small arterioles, is lipohyalinosis rather than atherosclerosis. These patients may present with a stuttering clinical course, and episodes are more stereotypical.

Less common obstructive vascular pathologies include fibromuscular dysplasia, arteritides, and dissection.

Embolism can occur from a proximal source such as the heart or from proximal vessels such as the aorta, carotid, or vertebral arteries. The embolic particle may form on heart valves or lesions within the heart (eg, clot, tumor), or in the venous circulation and paradoxically cross over to the arterial side through an intracardiac or transpulmonary shunt. Embolism may also be due to a hypercoagulable state.40 Embolic stroke is suspected when multiple vascular territories within the brain are clinically or radiographically affected.

Decreased systemic perfusion caused by severe heart failure or systemic hypotension can cause ischemia to the brain diffusely and bilaterally, limiting the ability of the blood-stream to wash out microemboli, especially in the border zones (also known as “watershed areas”), thus leading to ischemia or infarction.41 Decreased perfusion can also be local, due to a fixed vessel stenosis.

Using another classification system, a study in Rochester, MN, found the following incident rates of stroke subtypes, adjusted for age and sex, per 100,000 population42:

- Large-vessel cervical or intracranial atherosclerosis with more than 50% stenosis—27

- Cardioembolism—40

- Lacunar, small-vessel disease—25

- Uncertain cause—52

- Other identifiable cause—4.

THREE CLINICAL FEATURES SUGGEST TIA

TIAs can be hard to distinguish from nonischemic neurologic events in the acute setting such as an emergency room. Up to 60% of patients suspected of having a TIA actually have a nonischemic cause of their symptoms.43

Three clinical features suggest a TIA during the emergency room evaluation:

- Rapid onset of symptoms—“like lightning” or “in seconds,” in contrast to migraine and seizures, which develop over minutes

- No history of similar episodes in the past

- Absence of nonspecific symptoms—eg, stomach upset or tightness in the chest.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

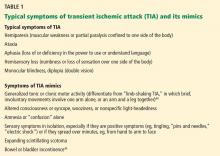

Because most TIA symptoms and signs have already resolved by the time of evaluation, the diagnosis depends on a careful history with special attention to the pace of onset and resolution, the duration and nature of the symptoms, circumstances at the time of symptom onset, previous similar episodes, associated features, vascular risk factors, and family history (Table 1).44,45

A detailed neurologic examination is imperative and should include fundoscopy. A cardiovascular assessment should include cardiac rhythm, bruits in the neck, orbits, and groin, peripheral pulses, and electrocardiography.

Do neurologists do a better job at diagnosing TIA and stroke?

Primary care physicians, internists, and emergency department physicians are often the ones to carry out the clinical assessment of possible TIA.

Determining if transient neurologic symptoms are caused by ischemia can be a challenge. When in doubt, referral to a neurologist with subspecialty training in cerebrovascular disease should be considered.

But do neurologists really do a better job? A recent study sought to compare the accuracy of diagnosis of TIA made by general practitioners, emergency physicians, and neurologists. The nonneurologists considered “confusion” and “unexplained fall” suggestive of TIA and “lower facial palsy” and “monocular blindness” less suggestive of TIA—whereas the opposite is true. This shows that nonneurologists often label minor strokes and several nonvascular transient neurologic disturbances as TIAs, and up to half of patients could be mislabeled as a result.46

Differences in diagnosing cerebrovascular events between emergency room physicians and attending neurologists have been tested,47 with an accuracy of diagnosis as low as 38% by emergency department physicians in one study.48 However, other studies did not show such a trend.49,50

A study at a university-based teaching hospital found the sensitivity of emergency room physician diagnosis to be 98.6% with a positive predictive value of 94.8%,49 showing that at a large teaching hospital with a comprehensive stroke intervention program, emergency physicians could identify patients with stroke, particularly hemorrhagic stroke, very accurately.

Improving the diagnosis of stroke and TIA

Routine use of imaging and involvement of a neurologist increase the sensitivity and accuracy of diagnosis. Education and written guidelines for acute stroke treatment both in the emergency department and in out-of-hospital settings seem to dramatically improve the rates of diagnostic accuracy and appropriate treatment.50

Emergency medical service personnel use two screening tools in the field to identify TIA and stroke symptoms:

- The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale, a three-item scale based on three signs: facial droop, arm drift, and slurring of speech51

- The Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen, which uses screening questions and asymmetry in the face, hand grip strength, and arm drift.52

Knowing that the patient is having a minor stroke or TIA is important. Urgent treatment of these conditions decreases the risk of stroke in the next 90 days, which was 10.5% in one study.5 Urgent assessment and early intervention could reduce this risk of subsequent stroke down to 2%.6