Clinical applications of pharmacogenetics: Present and near future

“Change is the only constant.”

—Heraclitus (c 535–475 bce)

With the cost of health care rising and money to pay for it shrinking, there has never been a greater need to reduce waste.

Ineffective treatments and adverse drug effects account for much preventable morbidity and expense. New treatments, touted as more potent, are often introduced as replacements for traditional ones that are still effective in many patients, adding to costs and the potential for harm. For the pharmaceutical industry, the search for new “blockbuster” drugs seems to have hit a wall, at least in cardiovascular medicine.1 Advances often come at the cost of adverse effects, such as bleeding with triple antiplatelet therapy and diabetes with potent statin drugs.

The path to maximizing benefit and reducing harm now appears to lie in stratifying populations and appreciating patient individuality in response to treatment. For many decades we have known that patients vary widely in their response to drugs, owing to personal factors such as body surface area, age, environment, and genetics. And indeed, we treat our patients as individuals, for example by tailoring aminoglycoside dose to weight and renal function.

However, clinical trials typically give us an idea of the benefits only to the average patient. While subgroup analyses identify groups that may benefit more or less from treatment, the additional information they provide is not easily integrated into the clinical model of prescribing, in which one size fits all.

THE PROMISE OF PHARMACOGENETICS

The emerging field of pharmacogenetics promises to give clinicians the tools to make informed treatment decisions based on predictive genetic testing. This genetic testing aims to match treatment to an individual’s genetic profile. This often involves analyzing single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes for enzymes that metabolize drugs, such as the cytochrome P450 enzymes, to predict efficacy or an adverse event with treatment.

Pharmacogenetics is playing an increasing role in clinical trials, particularly in the early stages of drug development, by helping to reduce the number of patients needed, prove efficacy, and identify subgroups in which alternative treatment can be targeted. At another level, a molecular understanding of disease is leading to truly targeted treatments based on genomics.

Over recent years, genetic testing has been increasingly used in clinical practice, thanks to a convergence of factors such as rapid, low-cost tests, a growing evidence base, and emerging interest among doctors and payers.

An advantage to using genetic testing as opposed to other types of laboratory testing, such as measuring the concentration of the drug in the blood during treatment, is that genetic tests can predict the response to treatment before the treatment is started. Moreover, with therapeutic drug monitoring after treatment has begun, there are sometimes no detectable measures of toxicity. For example, both carbamazepine and the antiviral drug abacavir can—fortunately only rarely—cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome. But before genetic markers were discovered, there was no method of estimating this risk apart from taking a family history.2,3 Considering the numbers of people involved, it was not feasible until recently to suggest genetic screening for patients starting on these drugs. However, the cost of genotyping and gene sequencing has been falling at a rate inversely faster than Moore’s law (an approximate annual doubling in computer power), and population genomics is becoming a reality.4

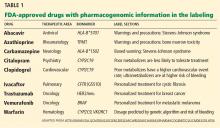

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes the current and future value of pharmacogenetics in drug safety and development. A number of approved pharmacogenetic biomarkers are listed on the FDA website (Table 1). Black box warnings have been mandated for a number of drugs on the basis of observational evidence.

The FDA also promotes rapid approval for novel drugs with pharmacogenetic “companion diagnostics.” A recent example of this was the approval of ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis patients who have the G551D mutation.5 Here, a molecular understanding of the condition led to the development of a targeted treatment. Although the cost of developing this drug was high, the path is now paved for similar advances. Oncologists are familiar with these advances with the emergence of new molecularly targeted treatments, eg, BRAF inhibitors in metastatic melanoma, imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia, and gefitinib in non-small-cell lung cancer.