Options for managing severe aortic stenosis: A case-based review

ABSTRACTThe treatment of calcific aortic stenosis is well established and includes careful monitoring of patients who have no symptoms and surgical aortic valve replacement in the patients who do have symptoms. Patients who cannot undergo open heart surgery can now undergo valve replacement via a minimally invasive transcatheter approach. In this article, we use clinical vignettes to illustrate the management of patients with severe aortic stenosis.

KEY POINTS

- Calcific aortic stenosis is the most common acquired valvular disease, and its prevalence is increasing as the population ages.

- Patients who have symptoms should be referred for aortic valve replacement. Patients who are not candidates for open heart surgery may be eligible for transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

- For high-risk patients with multiple comorbidities, “bridging” therapies such as aortic valvuloplasty are an option.

- In patients with aortic stenosis who present with hemodynamic instability and circulatory collapse, time can be gained with the use of intravenous sodium nitroprusside (in the absence of hypotension) or intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation while more definitive treatment decisions are being made.

Surgical aortic valve replacement remains the gold standard treatment for symptomatic aortic valve stenosis in patients at low or moderate risk of surgical complications. But this is a disease of the elderly, many of whom are too frail or too sick to undergo surgery.

Now, patients who cannot undergo this surgery can be offered the less invasive option of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Balloon valvuloplasty, sodium nitroprusside, and intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation can buy time for ill patients while more permanent mechanical interventions are being considered.

In this review, we will present several cases that highlight management choices for patients with severe aortic stenosis.

A PROGRESSIVE DISEASE OF THE ELDERLY

Aortic stenosis is the most common acquired valvular disease in the United States, and its incidence and prevalence are rising as the population ages. Epidemiologic studies suggest that 2% to 7% of all patients over age 65 have it.1,2

The natural history of the untreated disease is well established, with several case series showing an average decrease of 0.1 cm2 per year in aortic valve area and an increase of 7 mm Hg per year in the pressure gradient across the valve once the diagnosis is made.3,4 Development of angina, syncope, or heart failure is associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including death, and warrants prompt intervention with aortic valve replacement.5–7 Without intervention, the mortality rates reach as high as 75% in 3 years once symptoms develop.

Statins, bisphosphonates, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors have been used in attempts to slow or reverse the progression of aortic stenosis. However, studies of these drugs have had mixed results, and no definitive benefit has been shown.8–13 Surgical aortic valve replacement, on the other hand, normalizes the life expectancy of patients with aortic stenosis to that of age- and sex-matched controls and remains the gold standard therapy for patients who have symptoms.14

Traditionally, valve replacement has involved open heart surgery, since it requires direct visualization of the valve while the patient is on cardiopulmonary bypass. Unfortunately, many patients have multiple comorbid conditions and therefore are not candidates for open heart surgery. Options for these patients include aortic valvuloplasty and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. While there is considerable experience with aortic valvuloplasty, transcatheter aortic valve replacement is relatively new. In large randomized trials and registries, the transcatheter procedure has been shown to significantly improve long-term survival compared with medical management alone in inoperable patients and to have benefit similar to that of surgery in the high-risk population.15–17

CASE 1: SEVERE, SYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS IN A GOOD SURGICAL CANDIDATE

Mr. A, age 83, presents with shortness of breath and peripheral edema that have been worsening over the past several months. His pulse rate is 64 beats per minute and his blood pressure is 110/90 mm Hg. Auscultation reveals an absent aortic second heart sound with a late peaking systolic murmur that increases with expiration.

On echocardiography, his left ventricular ejection fraction is 55%, peak transaortic valve gradient 88 mm Hg, mean gradient 60 mm Hg, and effective valve area 0.6 cm2. He undergoes catheterization of the left side of his heart, which shows normal coronary arteries.

Mr. A also has hypertension and hyperlipidemia; his renal and pulmonary functions are normal.

How would you manage Mr. A’s aortic stenosis?

Symptomatic aortic stenosis leads to adverse clinical outcomes if managed medically without mechanical intervention,5–7 but patients who undergo aortic valve replacement have age-corrected postoperative survival rates that are nearly normal.14 Furthermore, thanks to improvements in surgical techniques and perioperative management, surgical mortality rates have decreased significantly in recent years and now range from 1% to 8%.18–20 The accumulated evidence showing clear superiority of a surgical approach over medical therapy has greatly simplified the therapeutic algorithm.21

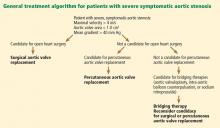

Consequently, the current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) give surgery a class I indication (evidence or general agreement that the procedure is beneficial, useful, and effective) for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (Figure 1). This level of recommendation also applies to patients who have severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis who are undergoing other types of cardiac surgery and also to patients with severe aortic stenosis and left ventricular dysfunction (defined as an ejection fraction < 50%).21

Mr. A was referred for surgical aortic valve replacement, given its clear survival benefit.