Electronic siloing: An unintended consequence of the electronic health record

DECLINE OF THE ‘CURBSIDE’ CONSULT

How does the subtle but sinister effect of electronic siloing really manifest itself at the bedside? I’ll offer an example from my personal clinical experience and then review similar examples from other clinical settings.

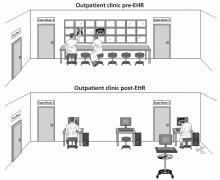

First, consider the following real change in clinical workflow that was caused by implementing the EHR in a pulmonary outpatient clinic and its impact on clinical hallway discussions among pulmonologists caring for their outpatients (Figure 1).

,The pre-EHR scene was a straight corridor of examination rooms with a long desk outside the rooms and a bank of x-ray viewboxes where clinicians would review films, gather their thoughts, and write notes before re-entering the patient’s room to discuss recommendations. This scene was undoubtedly common in outpatient clinics of all types around the world.

In the bygone era of paper charting and printed x-ray films, the pulmonologists seeing their patients in examination rooms along this corridor and seated next to one another while they wrote their notes would frequently turn to a colleague seated next to them and request a “curbside” consult, ie, an opinion on the films and the case. Typically, a brief, spontaneous conversation would follow, either confirming the requester’s impressions or raising some new, unconsidered approaches. The effect of these brief, spontaneous conversations was either a new diagnostic or treatment consideration or enhanced clinician confidence in the current plan of care. Each outcome has great merit.

Now consider the same scenario in the EHR era. Printed films and viewboxes are gone (which has the benefits of lower production cost and better film retrieval), and images are now reviewed digitally on computer workstations. Workstations are characteristically spread out along the corridor at distances or may be mounted on mobile platforms. Often, physicians now retreat to their nearby offices to write notes, allowing easier access to workstations or to use voice transcription software to record notes. The net effect of this physical separation and of the subtle but powerful change in workflow is that spontaneous curbside consults over a chest film are less likely to occur and, to the extent that such interactions enhance diagnostic accuracy, beneficial face-to-face clinical discussions are less likely. This is the risk of electronic siloing realized.

Defenders of the EHR will point out that the EHR does not preclude such face-to-face encounters. While technically this is correct, it is also equally true that such encounters are less likely because they no longer flow naturally from the workflow of writing a note side-by-side with colleagues with the films displayed nearby. Pressured for time, clinicians learn efficiency of motion and are simply less likely to leave their workstations to seek another colleague who, in turn, may be tethered to a workstation and absorbed in keyboarding and monitor-watching. The net effect is that such spontaneous face-to-face encounters are clearly less common in the EHR era.

Electronic siloing undoubtedly occurs in many other outpatient and inpatient settings in other specialties. For example, consults between orthopedic surgeons seeing outpatients must be similarly affected, as might be discussions between pathologists reviewing tissue slides on a multiheaded microscope vs individually at their own microscopes or work stations. Indeed, observations that computerized order entry isolates physicians from nurses and that the EHR undermines communication between inpatient health care providers6,8–11 represent other manifestations of electronic siloing.

Another variant of siloing occurs when there are not enough computers to go around. When clinicians seek but cannot find available workstations on the hospital ward, they move from the ward to their offices or other locations, separating them from the nurses and other physicians caring for those patients and, thereby, creating isolation and another form of siloing. A related theme is the importance of architecture in driving desirable interactions in the workplace in general and in hospitals in particular,17,18 where interchanges between health care providers are critical to enhancing quality of care.

OUT OF THE SILO, INTO THE FIELD

So, given the many clear benefits of the EHR and its current wave of adoption in health care, how can we maximize the benefits of the EHR while minimizing the adverse effects of electronic siloing?

The key point is that we must realize, appreciate, and prioritize the value of face-toface interaction among providers as we try to offer optimal care to patients with ever more complex clinical problems.

In doing so, clinical workspaces and the number and placement of workstations must be designed with an explicit intent and priority to encourage interchange between providers and to avoid electronic siloing. As an example related to reviewing images, imaging suites and clinics should be designed with the concept of a viewbox watering hole1 in which clinicians arrayed in a common space could review images on their individual computers but could easily prompt colleagues and send an image to a large, centrally visible monitor for the group’s review and comment. Furthermore, the EHR workflows themselves should drive caregivers to the patient rather than requiring their attention to the keyboard and the monitor. One could also imagine embedding secure social messaging within the EHR to encourage interactions among clinicians about pressing clinical challenges they are facing in the moment.

Overall, only through mindfulness of electronic siloing and of its subtle but adverse effects will we break out of the silos and emerge onto the fields of optimal health care.