A short story of the short QT syndrome

ABSTRACTShort QT syndrome is a recently recognized cause of cardiac rhythm disorders, including sudden cardiac death. Although the syndrome is rare, its potential lethality justifies routinely screening the electrocardiograms of patients with syncope or unexplained atrial or ventricular arrhythmias to look for this diagnosis. This review discusses recent advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis of this syndrome and outlines some of the challenges in establishing the diagnosis.

KEY POINTS

- Short QT syndrome is a genetic disease described initially in young patients who had atrial fibrillation or who died suddenly with no apparent structural heart disease.

- The diagnosis is established by the finding of a short QT interval. However, other factors including personal and family history are also important in establishing the diagnosis.

- The current recommendations for managing patients with short QT syndrome are not evidence-based. We encourage consultation with centers that have special interest in QT-interval-related disorders.

- Placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is considered the standard of care, especially in survivors of sudden cardiac death, ventricular fibrillation, or ventricular tachycardia. Unfortunately, a higher incidence of inappropriate shocks adds to the challenges of managing this potentially deadly disease.

Sudden cardiac death in a young person is a devastating event that has puzzled physicians for decades. In recent years, many of the underlying cardiac pathologies have been identified. These include structural abnormalities such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and nonstructural disorders associated with unstable rhythms that lead to sudden cardiac death.

The best known of these “channelopathies” are the long QT syndromes, which result from abnormal potassium and sodium channels in myocytes. Recently, interest has been growing in a disorder that may carry a similarly grim prognosis but that has an opposite finding on electrocardiography (ECG).

Short QT syndrome is a recently described heterogeneous genetic channelopathy that causes both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias and that has been documented to cause sudden cardiac death.

In 1996, a 37-year-old woman from Spain died suddenly; ECG several days earlier had shown a short QT interval of 266 ms.1 Two years later, an unrelated 17-year-old American woman undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy suddenly developed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response.1 Her QT interval was 225 ms. Her brother had a QT interval of 240 ms, and her mother’s was 230 ms. The patient’s maternal grandfather had a history of atrial fibrillation, and his QT interval was 245 ms. These cases led to the description of this new clinical syndrome (see below).2

CLINICAL FEATURES

Short QT syndrome has been associated with both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Atrial fibrillation, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation have all been well described. Patients who have symptoms usually present with palpitations, presyncope, syncope, or sudden or aborted cardiac death.3,4

ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

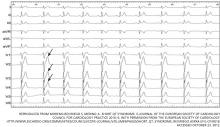

The primary finding on ECG is a short QT interval. However, others have been noted (Figure 1):

Short or absent ST segment

This finding is not merely a consequence of the short QT interval. In 10 patients with short QT syndrome, the distance from the J point to the peak T wave ranged from 80 to 120 ms. In 12 healthy people whose QT interval was less than 320 ms, this distance ranged from 150 ms to 240 ms.5

Tall and peaked T wave

A tall and peaked T wave is a common feature in short QT syndrome. However, it was also evident in people with short QT intervals who had no other features of the syndrome.5

QT response to heart rate

Normally, the QT interval is inversely related to the heart rate, but this is not true in short QT syndrome: the QT interval remains relatively fixed with changes in heart rate.6,7 This feature is less helpful in the office setting but may be found with Holter monitoring by measuring the QT interval at different heart rates.

BUT WHAT IS CONSIDERED A SHORT QT INTERVAL?

In clinical practice, the QT interval is corrected for the heart rate by the Bazett formula:

Corrected QT (QTc) = [QT interval/square root of the RR interval]

Review of ECGs from large populations in Finland (n = 10,822), Japan (n = 12,149), the United States (n = 79,743), and Switzerland (n = 41,676) revealed that a QTc value of 350 ms in males and 365 ms in females was 2.0 standard deviations (SD) below the mean.8–11 However, a QTc less than the 2.0 SD cutoff did not necessarily equal arrhythmogenic potential. This was illustrated in a 29-year follow-up study of Finnish patients with QTc values as short as 320 ms, in whom no arrhythmias were documented.8 Conversely, some patients with purported short QT syndrome had QTc intervals as long as 381 ms.12

Similar problems with uncertainty of values have plagued the diagnosis of long QT syndrome.13 The lack of reference ranges and the overlap between healthy and affected people called for the development of a scoring system that involves criteria based on ECG and on the clinical evaluation.14,15