Fever, dyspnea, and hepatitis in an Iraq veteran

CASE CONTINUED

The patient continued to feel sick and reported having three to four loose bowel movements per day and mild abdominal pain. His cough and dyspnea persisted.

He had not had contact with anyone who was ill, denied being exposed to animals or insects, and had not consumed unpasteurized dairy products; he recalled having cleaned his military-issue uniforms and equipment 2 to 3 weeks before the symptoms began. He called a military physician to get advice on what else could be causing his symptoms. This physician recommended tests based on potential exposures in Iraq. Tests for brucellosis, visceral leishmaniasis, and Q fever were ordered.

Over the next several days, he began to feel better, and at 3 to 4 weeks after the onset of his symptoms, he felt that he had returned to normal. All tests were negative.

TESTING FOR ATYPICAL PATHOGENS

2. Which of the following would be the most readily available method to confirm the diagnosis?

- Culture

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing

- Histopathologic testing

- Serologic testing

Testing for atypical pathogens was reasonable in this patient. In addition to an evaluation for parasitic causes of persistent and chronic diarrhea, an evaluation for Q fever, brucellosis, and visceral leishmaniasis via serologic testing was warranted. A variety of tests exist for all of these infections, but serologic tests are the most readily available.

Leishmaniasis testing

Visceral leishmaniasis was traditionally diagnosed by visualizing organisms in splenic or bone marrow aspirates,28 but now serologic tests are available through commercial and public health laboratories such as the CDC. Immunochromatographic tests using recombinant k39 antigen are highly sensitive and specific and have been used in military cases.29,30

Brucellosis testing

Brucella can be cultured from blood or tissue samples. The laboratory must be alerted, as special media can be used to increase the yield and precautions must be taken to prevent laboratory-acquired infection. Serologic testing is the method most commonly used for diagnosis.31

Q fever testing

Q fever can be diagnosed with serologic testing during its acute and convalescent phases.

PCR testing of blood is useful for diagnosing acute disease and is positive before serologic conversion, thus allowing rapid diagnosis and treatment.32 The Joint Biological Agent Identification and Diagnostic System (JBAIDS) PCR platform was studied in a Combat Support Hospital in Iraq for making the rapid diagnosis of Q fever and has since been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for military use.33

Culture is beyond the scope of most clinical laboratories and requires specialized cell culture or egg yolk media. In tissue, usually liver tissue obtained in an effort to evaluate hepatitis, the histologic finding of “doughnut” granulomas, or fibrin-encased granulomas, can be suggestive of C burnetii but may be nonspecific and seen with other infections.23,34

Serologic testing with an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) remains the most common method of diagnosis. It is based on the detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM responses against phase I and phase II antigens of C burnetii. After initial infection, the organism displays phase I antigens and is highly infectious. When grown in culture, the organism undergoes phase shifting to a less infectious form with predominantly phase II antigens. Paradoxically, after initial infection in humans, antibody response against phase II antigens is seen first, whereas in chronic infection, a phase I antibody response dominates.26,35 Phase II antibodies appear around week 2, and 90% of samples from infected people are positive by week 3. A fourfold rise in titer between the acute-phase and convalescent-phase samples confirms the diagnosis.35

A number of serologic assays are available worldwide, but they have different methods and cutoff values, so questions have arisen about the equivalence of the results.14,36 Serologic cutoffs have been defined in Europe, where most cases of Q fever have been reported.37

CHRONIC Q FEVER

3. Which of the following would be the most likely chronic manifestation of Q fever?

- Pneumonia

- Hepatitis

- Endocarditis

- Chronic fatigue

- Osteomyelitis

Chronic syndromes can develop years to months after untreated or inadequately treated infection and can be serious. Chronic infection can also result after a clinically silent initial infection.26,38 Culture-negative endocarditis, which occurs in fewer than 1% of patients diagnosed with acute infection, is the most common chronic manifestation (Table 1). Patients with underlying valvular disease, malignancy, or immunosuppression are at greater risk.38–40

Challenges and controversies

The diagnosis of chronic Q fever remains challenging. Traditionally, elevated phase I IgG titers were considered highly predictive of chronic disease. A cutoff of 1:800 was set, based on retrospective data from chronic cases in Europe, but its generalizability to different assays and patient populations has been unclear. 14,36,37 Recent reviews and prospective analysis with serial serologic studies in the Dutch outbreak and other sources suggest the positive predictive value (PPV) of phase I IgG titers greater than 1:800 to be lower than previously estimated, largely due to widespread testing and resultant increased seroprevalence assessments. It has been suggested the cutoff be raised to 1:1,600, which still only carries a 59% positive predictive value.41,42

Chronic fatigue due to Q fever remains a controversial topic and has only been described in Europe, Asia, and Australia. A direct link has yet to be established.43 Additional research is needed, but small studies of prolonged antibiotic treatment have not shown benefit in these cases.44

CASE CONTINUED

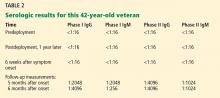

This patient did well. During a routine physical while enrolled at the Army War College in Carlisle, PA, 6 months after the original presentation, he mentioned his illness to the physician, who then repeated testing for Q fever; the test was positive (Table 2). Subsequently, serum samples from before and after his deployment were tested along with another convalescent-phase sample, and the results demonstrated Q fever seroconversion. He was well and had no physical complaints. He had no heart murmur, and a complete blood count and tests of liver enzymes and inflammatory markers were normal.

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION OF Q FEVER

4. Which of the following treatments would be appropriate, given his diagnosis of Q fever?

- Doxycycline (Vibramycin) 100 mg twice daily for 14 days

- Levofloxacin (Levaquin) 500 mg daily for 5 days

- Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 200 mg three times per day for 18 months

- No treatment

The treatment goals in Q fever are to hasten the resolution of symptoms and to prevent chronic disease. Generally, if there are no clinical findings or symptoms, treatment is not indicated. If the patient has symptoms, early treatment is preferred, but a response may be seen even when there is a delay in diagnosis.

Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 14 days is the treatment of choice. In addition, quinolones have in vitro activity,45 and a recent study suggests moxifloxacin (Avelox) may be the preferred antibiotic for those who cannot tolerate doxycycline.46 In pregnant women and in children, macrolides and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) are preferred.47,48

Treatment of chronic Q fever, in particular endocarditis, warrants more intensive therapy. A retrospective review of treated cases of endocarditis suggested that monotherapy with doxycycline often failed, and combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine has been advocated based on in vivo and in vitro experience.49