Aortic stenosis: Who should undergo surgery, transcatheter valve replacement?

ABSTRACTAortic stenosis, the most common valvular disease in the Western world, affects mainly people over age 60. It is characterized by years to decades of slow progression followed by rapid clinical deterioration and a high death rate once symptoms develop. Drug therapy for it remains ineffective, and surgical aortic valve replacement is the only effective long-term treatment. We discuss the indications for this surgery, with an emphasis on controversial conditions in which the indications are less well defined.

KEY POINTS

- The management of severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis is challenging. An abnormal response to exercise stress testing and elevated biomarkers may identify a higher-risk group that might benefit from closer followup and earlier surgery.

- Even patients with impaired left ventricular function and advanced disease can have a good outcome from surgery.

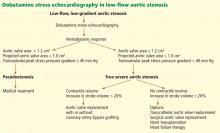

- Dobutamine infusion can help ascertain which patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic valve stenosis have true severe stenosis (as opposed to pseudostenosis) and are most likely to benefit from aortic valve replacement.

- Transcatheter aortic valve implantation will soon become the procedure of choice for patients at high risk for whom surgery is not feasible, and it may be an alternative to surgery in other patients at high risk even if they can undergo surgery.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Low-output, low-gradient aortic stenosis: True severe stenosis vs pseudostenosis

Patients with a low ejection fraction (< 50%) and a high mean transvalvular gradient (> 30 or 40 mm Hg) pose no therapeutic dilemma. They have true afterload mismatch and improve markedly with surgery.34 However, patients with an even lower ejection fraction (< 35% or 40%) and a low mean transvalvular gradient (< 30 or 40 mm Hg) pose more of a problem.

It is hard to tell if these patients have true severe aortic stenosis or pseudostenosis due to primary myocardial dysfunction. In pseudostenosis, the aortic valves are moderately diseased, and leaflet opening is reduced by a failing ventricle. When cardiac output is low, the formulae used to calculate the aortic valve area become less accurate, so that patients with cardiomyopathy who have only mild or moderate aortic stenosis may appear to have severe stenosis.

Patients with pseudostenosis have a high risk of dying during surgical aortic valve replacement, approaching 50%, and benefit more from evidence-based heart failure management.35,36 In patients with true stenosis, ventricular dysfunction is mainly a result of severe stenosis and should improve after aortic valve replacement.

Dobutamine stress echocardiography can be used in patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis to distinguish true severe stenosis from pseudostenosis. Dobutamine, an inotropic drug, increases the stroke volume so that patients with true severe aortic stenosis increase their transvalvular gradient and velocity with no or minimal change in the valve area. Conversely, in patients with pseudostenosis, the increase in stroke volume will open the aortic valve further and cause no or minimal increase in transvalvular gradient and velocity, but will increase the calculated valve area, confirming that aortic stenosis only is mild to moderate.37

Patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis are at higher risk during surgical aortic valve replacement. Many studies have reported a 30-day mortality rate between 9% and 18%, although risks vary considerably within this population.38,39

Contractile reserve. Dobutamine stress echocardiography has also been used to identify patients with severe aortic stenosis who can increase their ejection fraction and stroke volume (Figure 2).40,41 These patients are said to have “contractile reserve” and do better with surgery than those who lack adequate contractile reserve. Contractile reserve is defined as an increase of more than 20% in stroke volume during low-dose dobutamine infusion.42,43 In one small nonrandomized study, patients with contractile reserve had a 5% mortality rate at 30 days, compared with 32% in patients with no contractile reserve.44,45

In fact, patients with no contractile reserve have a high operative mortality rate during aortic valve replacement, but those who survive the operation have improvements in symptoms, functional class, and ejection fraction similar to those in patients who do have contractile reserve.46

On the other hand, if patients with no contractile reserve are treated conservatively, they have a much worse prognosis than those managed surgically.47 While it is true that patients without contractile reserve did not have a statistically significant difference in mortality rates with aortic valve replacement (P = .07) in a study by Monin et al,44 the difference was staggering between the group who underwent aortic valve replacement and the group who received medical treatment alone (hazard ratio = 0.47, 95% confidence interval 0.31–1.05, P = .07). The difference in the mortality rates may not have reached statistical significance because of the study’s small sample size.

A few years later, the same group published a similar paper with a larger study sample, focusing on patients with no contractile reserve. Using 42 propensity-matched patients, they found a statistically significantly higher 5-year survival rate in patients with no contractile reserve who underwent aortic valve replacement than in similar patients who received medical management (65% ± 11% vs 11 ± 7%, P = .019).47

Hence, surgery may be a better option than medical treatment for this select high-risk group despite the higher operative mortality risk. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation may also offer an interesting alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement in this particular subset of patients.48

Low-gradient ‘severe’ aortic stenosis with preserved ejection fraction or ‘paradoxically low-flow aortic stenosis’

Low-gradient “severe” aortic stenosis with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction is a recently recognized clinical entity in patients with severe aortic stenosis who present with a lower-than-expected transvalvular gradient on the basis of generally accepted values.49 (A patient with severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction is expected to generate a mean transaortic gradient greater than 40 mm Hg.24) This situation remains incompletely understood but has been shown in retrospective studies to foretell a poor prognosis.50–52

This subgroup of patients has pronounced left ventricular concentric remodeling with a small left ventricular cavity, impaired left ventricular filling, and reduced systolic longitudinal myocardial shortening.44

Herrmann et al53 provided more insight into the pathophysiology by showing that patients with this condition exhibit more pronounced myocardial fibrosis on myocardial biopsy and more pronounced late subendocardial enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging. These patients also displayed a significant decrease in mitral ring displacement and systolic strain. These abnormalities result in a low stroke volume despite a preserved ejection fraction and consequently a lower transvalvular gradient (< 40 mm Hg).

This disease pattern, in which the low gradient is interpreted as mild to moderate aortic stenosis, may lead to underestimation of stenosis severity and, thus, to inappropriate delay of aortic valve replacement.

However, other conditions can cause this hemodynamic situation with a lower-than-expected gradient. It can arise from a small left ventricle that correlates with a small body size, yielding a lower-than-normal stroke volume, measurement errors in determining stroke volume and valve area by Doppler echocardiography, systemic hypertension (which can influence estimation of the gradient by Doppler echocardiography), and inconsistency in the definition of severe aortic stenosis in the current guidelines relating to cutoffs of valve area in relation to those of jet velocity and gradient.54

This subgroup of patients seems to be at a more advanced stage and has a poorer prognosis if treated medically rather than surgically. When symptomatic, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis should be treated surgically, with one study showing excellent outcomes with aortic valve replacement.50

However, a recent study by Jander et al55 showed that patients with low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and normal ejection fraction have outcomes similar to those in patients with moderate aortic stenosis, suggesting a strategy of medical therapy and close monitoring.55 Of note, the subset of patients reported in this substudy of the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial did not really fit the pattern of low-gradient severe aortic stenosis described by Hachicha et al50 and other groups.51,56 These patients had aortic valve areas in the severe range but mean transaortic gradients in the moderate range, and in light of the other echocardiographic findings in these patients, the area-gradient discordances were predominantly due to small body surface area and measurement errors. These patients indeed had near-normal left ventricular size, no left ventricular hypertrophy, and no evidence of concentric remodeling.

Finally, the findings of the study by Jander et al55 are discordant with those of another substudy of the SEAS trial,57 which reported that paradoxical low-flow aortic stenosis occurred in about 7% of the cohort (compared with 52% in the study by Jander et al55) and was associated with more pronounced concentric remodeling and more severe impairment of myocardial function.

Whether intervention in patients with low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and valve area less than 1.0 cm2 improves outcomes remains to be confirmed and reproduced in future prospective studies.