Dengue: A reemerging concern for travelers

ABSTRACTDengue, a neglected tropical disease that is reemerging around the world, became a nationally notifiable disease in the United States in 2009. Travel to tropical and subtropical areas in the developing world poses the greatest risk of infection for US residents, and an increase in travel to these areas makes this infection more likely to be seen by primary care physicians in their practices.

KEY POINTS

- Dengue results from infection with one of four distinct serotypes: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4.

- The most common outcome after infection by the bite of an Aedes mosquito (which bites in the daytime) is asymptomatic infection, a flulike illness, or classic self-limited dengue fever. Severe, life-threatening disease with hemorrhagic manifestations or shock is rare.

- Obtaining a history of recent travel to a dengue-endemic area is a key in evaluating a person presenting with undifferentiated fever or a fever-rash-arthralgia syndrome.

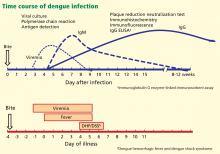

- Diagnostic testing is based on the natural history of infection; antibody levels begin to rise as levels of viremia begin to decline.

- Risk factors help predict who will develop severe dengue after primary or secondary infection.

THE CLINICAL SPECTRUM OF DENGUE VIRUS INFECTION

Most primary and secondary dengue infections are asymptomatic.8 The common forms of clinically apparent disease include self-limited, undifferentiated fever and classic dengue fever (Figure 3). Severe disease, manifesting as either dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome, is a rare outcome of dengue virus infection, estimated to occur in 1% of cases worldwide.31 However, the true proportion of severe infection among all dengue cases seen in travelers is difficult to assess reliably.

Asymptomatic infection

Clinical dengue disease is relatively uncommon, as between 60% and 80% of infections are asymptomatic, particularly in children and adults who never have been infected before.32

In the recent outbreak in Key West, 28 symptomatic cases of locally acquired dengue were detected. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted a serologic survey of 240 healthy, randomly selected residents of Key West and found evidence of recent infection in 5.4% of those tested.28 Based on this finding, the CDC estimated that 1,000 people had been infected, of whom more than 90% had no symptoms. However, no attempt was made to differentiate primary from secondary infection in this serosurvey. (Previous infection with one dengue serotype places some individuals at risk for severe dengue if infected with a different serotype in the future.)

Uncomplicated dengue infection

Undifferentiated fever33 and classic dengue fever are the most common manifestations of clinical dengue infection. Also known as breakbone fever, classic dengue fever is a fever-arthralgia-rash syndrome.1

The onset is acute, with a high fever (though rarely greater than 40.5°C [104.9°F]) 3 to 14 days (usually 5 to 9 days) after the patient was bitten by an Aedes mosquito. Therefore, a febrile illness beginning more than 2 weeks after returning from travel to an endemic area is unlikely to be dengue, and another diagnosis should be sought.

A prodrome of headache, backache, fatigue, chills, anorexia, and occasionally a rash may precede the onset of fever by about 12 hours.

With fever comes a severe frontal headache, associated retro-orbital pain with eye movement, and conjunctival injection.

Some patients develop a bright, erythematous, maculopapular eruption 2 to 6 days into the illness that appears first on the trunk and then spreads to the face and extremities, with characteristic islands of unaffected skin throughout the involved area.34

Severe back or groin pain occurs in about 60% of adult patients.35

Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are common.

Patients remain febrile for about 5 days, although some experience a biphasic (saddleback) fever that declines after 2 to 3 days, only to recur in about 24 hours.

In some patients, relative bradycardia is seen 2 to 3 days after fever onset.

Lymphadenopathy, sore throat, diarrhea or constipation, cutaneous hypesthesia, dysuria, dysgeusia, hepatitis, aseptic meningitis, and encephalopathy with delirium have been reported. Splenomegaly is rare.

In classic dengue fever, initial neutropenia and lymphopenia with subsequent lymphocytosis and monocytosis are often noted.

Mild hepatitis can be seen; aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels can be two to three times the upper limit of normal.

Hemorrhagic manifestations, eg, petechiae, gingival bleeding, and epistaxis, may be seen in patients with mild thrombocytopenia even if they have no evidence of hemoconcentration or evidence of vascular instability.18

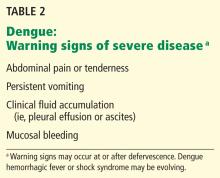

Although clinical dengue infection is usually self-limiting, acute symptoms can be incapacitating and can require hospitalization,36 and convalescence may take several months because of ongoing asthenia or depression.37 Furthermore, certain critical findings should alert the clinician to possible impending severe dengue and should lead to hospitalization for further observation until evolution to severe dengue has been ruled out (Table 2).

Severe dengue: Hemorrhagic fever and shock syndrome

In a very small subset of patients, dengue infection develops into a severe, potentially lifethreatening illness. Fortunately, this has rarely been reported in travelers.38

Dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome arise just as fever is subsiding. They constitute a spectrum of severe illness (Figure 4). Dengue hemorrhagic fever is poorly understood because its hemorrhagic manifestations are not of themselves diagnostic of the condition, as petechiae, epistaxis, and gingival bleeding may be seen in classic dengue fever (Figure 3) without progression to more severe illness.

The differentiating characteristic of severe dengue, in addition to hemorrhagic manifestations, is objective evidence of plasma leakage.39 Impending shock is suggested by the new onset of severe abdominal pain, restlessness, hepatomegaly, hypothermia, and diaphoresis.

The mechanisms causing the severe hemorrhagic manifestations characteristic of dengue hemorrhagic fever and the sudden onset of vascular permeability underlying dengue shock syndrome are not understood.40 Many hypotheses have been generated and risk factors identified from observational and retrospective analyses. These include T-cell immune-pathologic responses involving receptors, antibodies, and cytokines,41 as well as specific host-genetic characteristics,42,43 age,44,45 sex,46 comorbid conditions,47–49 dengue virus virulence factors,50 sequence of dengue infection, and infection parity.51 One hypothesis is that antibody-dependent enhancement of virus occurs during infection with a second dengue serotype after infection with a different serotype in the past, and that this may be the root cause of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. However, this has not been proven.40

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS FOR VIRUS, ANTIGENIC FRAGMENTS, ANTIBODIES

The appropriate test to confirm dengue virus infection is based on the natural history of the infection (Figure 4) coupled with the exposure risk in the returned traveler. These tests include isolation of the virus using cell culture, identification of antigenic fragments (test not available in the United States), and serologic tests for specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or neutralization assays.52 During primary infection, viremia and antigenemia usually parallel fever, but when a person is later infected with a different dengue serotype, the period of viremia may be as short as 2 to 3 days, with antigens persisting in the serum for several more days.40 Virus isolation is not routinely available but is both sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of dengue virus infection during the viremic period.

If polymerase chain reaction testing, dengue antigen capture ELISA, or virus isolation testing is not available, the ideal confirmatory procedure is to test for dengue IgM (looking for conversion from negative to positive), IgG (looking for a fourfold rise in antibody), or both, in paired serum samples collected 2 weeks apart, with the initial sample collected less than 5 days after the onset of symptoms. A presumptive diagnosis can be made if a single blood sample collected more than 7 days after symptom onset is found to have dengue IgM antibody. A single blood sample for IgM collected earlier than 7 days after the onset of illness may give a false-negative result (Figure 4) in infected persons.