Hyperpigmentation and hypotension

A 65-year-old man presents with a 2-month history of generalized weakness, dizziness, and blurred vision. His symptoms began gradually and have been progressing over the last few weeks, so that they now affect his ability to perform normal daily activities.

He has lost 20 lb and has become anorectic. He has no fever, night sweats, headache, cough, hemoptysis, or dyspnea. He has no history of abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, nausea, vomiting, or urinary symptoms. He was admitted 6 weeks ago for the same symptoms; he was treated for hypotension and received intravenous (IV) fluids and electrolyte supplements for dehydration.

He has a history of hypertension, stroke, vascular dementia, and atrial fibrillation. He is taking warfarin (Coumadin), extended-release diltiazem (Cardizem), simvastatin (Zocor), and donepezil (Aricept). He underwent right hemicolectomy 5 years ago for a large tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia in the cecum.

,Initial laboratory values are as follows:

- White blood cell count 7.4 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0), with a normal differential

- Mild anemia, with a hemoglobin of 116 g/L (140–175)

- Activated partial thromboplastin time 59.9 sec (23.0–32.4)

- Serum sodium 135 mmol/L (136–142)

- Serum potassium 4.6 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 58 U/L (10–30)

- Alanine aminotransferase 16 U/L (10–40)

- Alkaline phosphatase 328 U/L (30–120)

- Urea, creatinine, and corrected calcium are normal.

Electrocardiography shows atrial fibrillation with low-voltage QRS complexes. Chest radiography is normal. A stool test is negative for occult blood. A workup for sepsis is negative.

Q: Which is the appropriate test at this point to determine the cause of the hypotension?

- Serum parathyroid-hormone-related protein

- Baseline serum cortisol, plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels, and an ACTH stimulation test with cosyntropin (Cortrosyn)

- Serum thyrotropin level

- Aspiration biopsy of subcutaneous fat with Congo red and immunostaining

- Late-night salivary cortisol

A: The correct next step is to measure baseline serum cortisol, to test ACTH levels, and to order an ACTH stimulation test with cosyntropin.

Primary adrenocortical insufficiency should be considered in patients with metastatic malignancy who present with peripheral vascular collapse, particularly when it is associated with cutaneous hyperpigmentation, chronic malaise, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, hypoglycemia, and electrolyte disturbances such as hyponatremia and hyperkalemia.

Checking the baseline serum cortisol and ACTH levels and cosyntropin stimulation testing are vital steps in making an early diagnosis of primary adrenocortical insufficiency. Inappropriately low serum cortisol is highly suggestive of primary adrenal insufficiency, especially if accompanied by simultaneous elevation of the plasma ACTH level. The result of the ACTH stimulation test with cosyntropin is often confirmatory.

Measuring the serum parathyroid-hormone-related protein level is not indicated, since the patient has a normal corrected calcium. Patients with ectopic Cushing syndrome may present with weight loss due to underlying malignancy, but the presence of hypotension and a lack of hypokalemia makes such a diagnosis unlikely, and, therefore, measurement of late-night salivary cortisol is not the best answer. Amyloidosis, hypothyroidism, or hyperthyroidism are unlikely to have this patient’s presentation.

RESULTS OF FURTHER EVALUATION

Our patient’s ACTH serum level was elevated, and an ACTH stimulation test with cosyntropin confirmed the diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency.

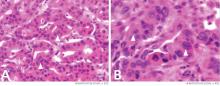

CT of the abdomen failed to demonstrate primary tumors, but both adrenal glands were enlarged, likely from metastasis (Figure 4). His hypotension responded to treatment with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone, and his symptoms resolved. No further testing or therapy was directed to the primary occult malignancy, as it was considered advanced. The prognosis was discussed with the patient, and he deferred any further management and was discharged to hospice care. He died a few months later.