Hypertension in the elderly: Some practical considerations

ABSTRACTData from randomized controlled trials suggest that treating hypertension in the elderly, including octogenarians, may substantially reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and death. However, treatment remains challenging because of comorbidities and aging-related changes. We present common case scenarios encountered while managing elderly patients with hypertension, including secondary hypertension, adverse effects of drugs, labile hypertension, orthostatic hypotension, and dementia.

KEY POINTS

- Therapy should be considered in all aging hypertensive patients, even the very elderly (> 80 years old).

- Most antihypertensive drugs can be used as first-line treatment in the absence of a compelling indication for a specific class, with the possible exception of alpha-blockers and beta-blockers.

- An initial goal of less than 140/90 mm Hg is reasonable in elderly patients, and an achieved systolic blood pressure of 140 to 145 mm Hg is acceptable in octogenarians.

- Start with low doses; titrate upward slowly; and monitor closely for adverse effects.

- Thiazide diuretics should be used with caution in the elderly because of the risk of hyponatremia.

MANAGEMENT APPROACH IN THE ELDERLY

Blood pressure should be recorded in both arms before a diagnosis is made. In a number of patients, particularly the elderly, there are significant differences in blood pressure readings between the two arms. The higher reading should be relied on and the corresponding arm used for subsequent measurements.

Lifestyle interventions

Similar to the approach in younger patients with hypertension, lifestyle interventions are the first step to managing high blood pressure in the elderly. The diet and exercise interventions in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) trial have both been shown to lower blood pressure.10,11

Restricting sodium intake has been shown to lower blood pressure more in older adults than in younger adults. In the DASH trial,12 systolic blood pressure decreased by 8.1 mm Hg with sodium restriction in hypertensive patients age 55 to 76 years, compared with 4.8 mm Hg for adults aged 23 to 41 years. In the Trial of Nonpharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly (TONE),13 in people ages 60 to 80 who were randomized to reduce their salt intake, urinary sodium excretion was 40 mmol/day lower and blood pressure was 4.3/2.0 mm Hg lower than in a group that received usual care. Accordingly, reducing salt intake is particularly valuable for blood pressure management in the salt-sensitive elderly.14

Drug therapy

The hypertension pandemic has driven extensive pharmaceutical research, and new drugs continue to be introduced. The major classes of drugs commonly used for treating hypertension are diuretics, calcium channel blockers, and renin-angiotensin system blockers. Each class has specific benefits and adverse-effect profiles.

It is appropriate to start antihypertensive drug therapy with the lowest dose and to monitor for adverse effects, including orthostatic hypotension. The choice of drug should be guided by the patient’s comorbid conditions (Table 1) and the other drugs the patient is taking.15 If the blood pressure response is inadequate, a second drug from a different class should be added. In the same manner, a third drug from a different class should be added if the blood pressure remains outside the optimal range on two drugs.

The average elderly American is on more than six medications.16 Some of these are for high blood pressure, but others interact with antihypertensive drugs (Table 2), and some, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids, directly affect blood pressure. Therefore, the drug regimen of an elderly hypertensive patient should be reviewed carefully at every visit. The Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions (STOPP), a list of 65 rules relating to the most common and most potentially dangerous instances of inappropriate prescribing and overprescribing in the elderly,17 has been found to be a reliable tool in this regard, with a kappa-coefficient of 0.75. Together with the Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to Right [ie, Appropriate, Indicated] Treatment (START),17 which lists 22 evidence-based prescribing indicators for common conditions in the elderly, these criteria provide clinicians with an easy screening tool to combat polypharmacy.

Given the multitude of factors that go into deciding on a specific management strategy in the elderly, it is not possible to discuss individualized care in all patients in the scope of one paper. Below, we present several case scenarios that internists commonly encounter, and suggest ways to approach each.

CASE 1: SECONDARY HYPERTENSION

A 69-year-old obese man who has hypertension of recent onset, long-standing gastroesophageal reflux disease, and benign prostatic hypertrophy comes to your office, accompanied by his wife. He has never had hypertension before. His body mass index is 34 kg/m2. On physical examination, his blood pressure is 180/112 mm Hg.

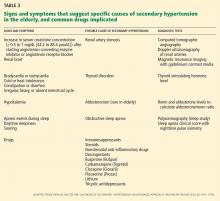

We start with this case to emphasize the importance of considering causes of secondary hypertension in all patients with the disease (Table 3).18 Further workup should be pursued in those who appear to have “inappropriate” hypertension. This could present as refractory hypertension, abrupt-onset hypertension, hypertension that is first diagnosed before age 20 or after age 60, or loss of control over previously well-controlled blood pressure. Secondary hypertension must always be considered when the history or physical examination suggests a possible cause.

Renal artery stenosis increases in incidence with age. Its prevalence is reported to be as high as 50% in elderly patients with other signs of atherosclerosis such as widespread peripheral artery disease.19

Obstructive sleep apnea also commonly coexists with hypertension and its prevalence also increases with age. In addition, elderly patients with obstructive sleep apnea have a higher incidence of cardiovascular complications, including hypertension, than middle-aged people.20 Numerous studies have found that the severity of obstructive sleep apnea corresponds with the likelihood of systemic hypertension.21–23 Randomized trials and meta-analyses have also concluded that effective treatment with continuous positive airway pressure reduces systemic blood pressure,24–27 although by less than antihypertensive medications do.

A causal relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension has not been established with certainty. It is recommended, however, that patients with resistant hypertension be screened for obstructive sleep apnea as a possible cause of their disease.

Other causes of secondary hypertension to keep in mind when evaluating patients who have inappropriate hypertension include thyroid disorders, alcohol and tobacco use, and chronic steroid or NSAID use. Pheochromocytoma and adrenal adenoma, though possible, are less prevalent in the elderly.

Case continued

Physical examination in the above patient revealed an epigastric systolic-diastolic bruit, a sign that, although not sensitive, is highly specific for renal artery stenosis, raising the suspicion of this condition. Duplex ultrasonography of the renal arteries confirmed this suspicion. The patient underwent angiography and revascularization, resulting in a distinct fall in, but not normalization of, his blood pressure.