Updates in the medical management of Parkinson disease

ABSTRACTMost, if not all, currently available drugs for Parkinson disease address dopaminergic loss and relieve symptoms. However, their adverse effects can be limiting and they do not address disease progression. Moreover, nonmotor features of Parkinson disease such as depression, dementia, and psychosis are now recognized as important and disabling. A cure remains elusive. However, promising interventions and agents are emerging. As an example, people who exercise regularly are less likely to develop Parkinson disease, and if they develop it, they tend to have slower progression.

KEY POINTS

- Parkinson disease can usually be diagnosed on the basis of clinical features: slow movement, resting tremor, rigidity, and asymmetrical presentation, as well as alleviation of symptoms with dopaminergic therapy.

- Early disease can be treated with levodopa, dopamine agonists, anticholinergics, and monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors.

- Advanced Parkinson disease may require a catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor, apomorphine, and amantadine (Symmetrel). Side effects include motor fluctuations, dyskinesias, and cognitive problems.

MANAGING PARKINSON DISEASE

Nonpharmacologic therapy is very important. Because patients tend to live longer because of better treatment, education is particularly important. The benefits of exercise go beyond general conditioning and cardiovascular health. People who exercise vigorously at least three times a week for 30 to 45 minutes are less likely to develop Parkinson disease and, if they develop it, they tend to have slower progression.

Prevention with neuroprotective drugs is not yet an option but hopefully will be in the near future.

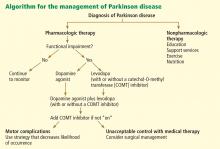

Drug treatment generally starts when the patient is functionally impaired. If so, either levodopa or a dopamine agonist is started, depending on the patient’s age and the severity of symptoms. With increasing severity, other drugs can be added, and when those fail to control symptoms, surgery should be considered.

Deep brain stimulation surgery can make a tremendous difference in a patient’s quality of life. Other than levodopa, it is probably the best therapy available; however, it is very expensive and is not without risks.

Levodopa: The most effective drug, until it wears off

All current drugs for Parkinson disease activate dopamine neurotransmission in the brain. The most effective—and the cheapest—is still carbidopa/levodopa (Sinemet, Parcopa, Atamet). Levodopa converts to dopamine both peripherally and after it crosses the blood-brain barrier. Carbidopa prevents the peripheral conversion of levodopa to dopamine, reducing the peripheral adverse effects of levodopa, such as nausea and vomiting. The combination drug is usually given three times a day, with different doses available (10 mg carbidopa/100 mg levodopa, 25/100, 50/200, and 25/250) and as immediate-release and controlled-release formulations as well as an orally dissolving form (Parcopa) for patients with difficulty swallowing.

The major problem with levodopa is that after 4 to 6 years of treatment, about 40% of patients develop motor fluctuations and dyskinesias.5 If treatment is started too soon or at too high a dose, these problems tend to develop even earlier, especially among younger patients.

Motor fluctuations can take many forms: slow wearing-off, abrupt loss of effectiveness, and random on-and-off effectiveness (“yo-yoing”).

Dyskinesias typically involve constant chorea (dance-like) movements and occur at peak dose. Although chorea is easily treated by lowering the dosage, patients generally prefer having these movements rather than the Parkinson symptoms that recur from underdosing.

Dopamine agonists may be best for younger patients in early stages

The next most effective class of drugs are the dopamine agonists: pramipexole (Mirapex), ropinirole (Requip), and bromocriptine (Parlodel). A fourth drug, pergolide, is no longer available because of associated valvular heart complications. Each can be used as monotherapy in mild, early Parkinson disease or as an additional drug for moderate to severe disease. They are longer-acting than levodopa and can be taken once daily. Although they are less likely than levodopa to cause wearing-off or dyskinesias, they are associated with more nonmotor side effects: nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, confusion, somnolence or sleep attacks, low blood pressure, edema, and impulse control disorders.

Multiple clinical trials have been conducted to test the efficacy of dopamine agonists vs levodopa for treating Parkinson disease.6–9 Almost always, levodopa is more effective but involves more wearing-off and dyskinesias. For this reason, for patients with milder parkinsonism who may not need the strongest drug available, trying one of the dopamine agonists first may be worthwhile.

In addition, patients younger than age 60 are more prone to develop motor fluctuations and dyskinesias, so a dopamine agonist should be tried first in patients in that age group. For patients over age 65 for whom cost may be of concern, levodopa is the preferred starting drug.

Anticholinergic drugs for tremor

Before 1969, only anticholinergic drugs were available to treat Parkinson disease. Examples include trihexyphenidyl (Artane, Trihexane) and benztropine (Cogentin). These drugs are effective for treating tremor and drooling but are much less useful against rigidity, bradykinesia, and balance problems. Side effects include confusion, dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, urinary retention, and cognitive impairment.

Anticholinergics should only be considered for young patients in whom tremor is a large problem and who have not responded well to the traditional Parkinson drugs. Because tremor is mostly a cosmetic problem, anticholinergics can also be useful for treating actors, musicians, and other patients with a public role.

Monoamine oxidase B inhibitors are well tolerated but less effective

In the brain, dopamine is broken down by monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B); therefore, inhibiting this enzyme increases dopamine’s availability. The MAO-B inhibitors selegiline (Eldepryl, Zelapar) and rasagiline (Azilect) are effective for monotherapy for Parkinson disease but are not as effective as levodopa. Most physicians feel MAO-B inhibitors are also less effective than dopamine agonists, although double-blind, randomized clinical trials have not proven this.6,10,11

MAO-B inhibitors have a long half-life, allowing once-daily dosing, and they are very well tolerated, with a side-effect profile similar to that of placebo. As with all MAO inhibitors, caution is needed regarding drug and food interactions.