Imaging for autonomic dysfunction

ABSTRACT

Direct visualization of heart-brain interactions is the goal when assessing autonomic nervous system function. Cortical topology relevant to neuroimaging consists of the cingulate, insula, and amygdala, all of which share proximity to the basal ganglia. Significant cardiac effects stemming from brain injury are well known, including alteration of cardiac rhythms, cardiac variability, and blood pressure regulation; in some instances, these effects may correlate with neuroimaging, depending on the region of the brain involved. It is difficult to achieve visualization of areas within the brainstem that govern autonomic responses, although investigators have identified brain correlates of autonomic function with the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging and electrocardiographic data obtained simultaneously. The potential utility of brain imaging in sick patients may be limited because of challenges such as the magnetic resonance imaging environment and blunted autonomic responses, but continued investigation is warranted.

FUNCTIONAL BRAIN IMAGING IN GENERAL

Direct visualization of heart-brain interactions is the goal when assessing ANS function. Positron emission tomography (PET) produces quantitative images, but spatial and temporal resolutions are vastly superior with fMRI.11 Further, radiation exposure is low with fMRI, allowing for safe repeat imaging.

Ogawa et al12 first demonstrated that in vivo images of brain microvasculature are affected by blood oxygen level, and that blood oxygenation reduced vascular signal loss. Therefore, blood oxygenation level–dependent (BOLD) contrast added to MRI could complement PET-like measurements in the study of regional brain activity.

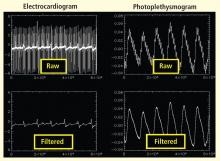

Bilateral finger tapping with intermittent periods of rest is associated with a pattern of increasing and decreasing intensity of fMRI signals in involved brain regions that reflect the periods of activity and rest. This technique has been used to locate brain voxels with similar patterns of activity, enabling the creation of familiar color brain mapping. A challenge posed by autonomic fMRI in such brain mapping is that fMRI is susceptible to artifacts (Figure 3). For example, a movement of the head as little as 1 mm inside the MRI scanner—a distance comparable to the size of autonomic structures—can produce a motion artifact (false activation of brain regions) that can affect statistical significance. In addition, many ANS regions of the brain are near osseous structures (for example the brainstem and skull base) that cause signal distortion and loss.

REQUIREMENTS FOR AUTONOMIC fMRI

The tasks chosen to visualize brain control of autonomic function must naturally elicit an autonomic response. The difficulty is that untrained persons have little or no volitional control over autonomic functions, so the task and its analysis must be designed carefully and be MRI-compatible. Any motion will degrade the image; further, the capacity for the MRI environment to corrupt the measurements can limit the potential tasks for measurement.

Possible stimuli for eliciting a sympathetic response include pain, fear, anticipation, anxiety, concentration or memory, cold pressor, Stroop test, breathing tests, and maximal hand grip. Examples of parasympathetic stimuli are the Valsalva maneuver and paced breathing. The responses to stimuli (ie, heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure, galvanic skin response, papillary response) must be monitored to compare the data obtained from fMRI. MRI-compatible equipment is now available for measuring many of these responses.

Identifying areas activated during tasks

Functional neuroimaging with PET and fMRI has shown consistently that the anterior cingulate is activated during multiple tasks designed to elicit an autonomic response (gambling anticipation, emotional response to faces, Stroop test).11

In a study designed to test autonomic interoceptive awareness, subjects underwent fMRI while they were asked to judge the timing of their heartbeats to auditory tones that were either synchronized with their heartbeat or delayed by 500 msec.13 Areas of enhanced activity during the task were the right insular cortex, anterior cingulate, parietal lobes, and operculum.

Characterizing brainstem sites

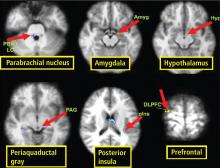

It is difficult to achieve visualization of areas within the brainstem that govern autonomic responses. These regions are small and motion artifacts are common because of brainstem movement with the cardiac pulse. With fMRI, Topolovec et al14 were able to characterize brainstem sites involved in autonomic control, demonstrating activation of the nucleus of the solitary tract and parabrachial nucleus.

A review of four fMRI studies of stressor-evoked blood pressure reactivity demonstrated activation in corticolimbic areas, including the cingulate cortex, insula, amygdala, and cortical and subcortical areas that are involved in hemodynamic and metabolic support for stress-related behavioral responses.16