A 49-year-old woman with a persistent cough

Highly contagious

Pertussis is transmitted person-to-person, primarily through aerosolized droplets from coughing or sneezing or by direct contact with secretions from the respiratory tract of infected persons. It is highly contagious, with secondary attack rates of up to 80% in susceptible people.

A three-stage clinical course

The clinical definition of pertussis used by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists is an acute cough illness lasting at least 2 weeks, with paroxysms of coughing, an inspiratory “whoop,” or posttussive vomiting without another apparent cause.5

The clinical course of the illness is traditionally divided into three stages:

The catarrhal phase typically lasts 1 to 2 weeks and is clinically indistinguishable from a viral upper respiratory infection. It is characterized by the insidious onset of malaise, coryza, sneezing, low-grade fever, and a mild cough that gradually becomes severe.6

The paroxysmal phase normally lasts 1 to 6 weeks but may persist for up to 10 weeks. The diagnosis of pertussis is usually suspected during this phase. The classic features of this phase are bursts or paroxysms of numerous, rapid coughs. These are followed by a long inspiratory effort usually accompanied by a characteristic high-pitched whoop, most notably observed in infants and children. Infants and children may appear very ill and distressed during this time and may become cyanotic, but cyanosis is uncommon in adults and adolescents. The paroxysms may also be followed by exhaustion and posttussive vomiting. In some cases, the cough is not paroxysmal, but rather simply persistent. The coughing attacks tend to occur more often at night, with an average of 15 attacks per 24 hours. During the first 1 to 2 weeks of this stage, the attacks generally increase in frequency, remain at the same intensity level for 2 to 3 weeks, and then gradually decrease over 1 to 2 weeks.1,7

The convalescent phase can have a variable course, ranging from weeks to months, with an average duration of 2 to 3 weeks. During this stage, the paroxysms of coughing become less frequent and gradually resolve. Paroxysms often recur with subsequent respiratory infections.

In infants and young children, pertussis tends to follow these stages in a predictable sequence. Adolescents and adults, however, tend to go through the stages without being as ill and typically do not exhibit the characteristic whoop.

TESTING FOR PERTUSSIS

2. Which would be the test of choice to confirm pertussis in this patient?

- Bacterial culture of nasopharyngeal secretions

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of nasopharyngeal secretions

- Direct fluorescent antibody testing of nasopharyngeal secretions

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) serologic testing

Establishing the diagnosis of pertussis is often rather challenging.

Bacterial culture: Very specific, but slow and not so sensitive

Bacterial culture is still the gold standard for diagnosing pertussis, as a positive culture for B pertussis is 100% specific.5

However, this test has drawbacks. Its sensitivity has a wide range (15% to 80%) and depends very much on the time from the onset of symptoms to the time the culture specimen is collected. The yield drops off significantly after 1 week, and after 3 weeks the test has a sensitivity of only 1% to 3%.8 Therefore, for our patient, who has had symptoms for 3 weeks already, bacterial culture would not be the best test. In addition, the results are usually not known for 7 to 14 days, which is too slow to be useful in managing acute cases.

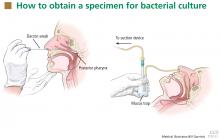

For swabbing, a Dacron swab is inserted through the nostril to the posterior pharynx and is left in place for 10 seconds to maximize the yield of the specimen. Recovery rates for B pertussis are low if the throat or the anterior nasal passage is swabbed instead of the posterior pharynx.9

Nasopharyngeal aspiration is a more complicated procedure, requiring a suction device to trap the mucus, but it may provide higher yields than swabbing.10 In this method, the specimen is obtained by inserting a small tube (eg, an infant feeding tube) connected to a mucus trap into the nostril back to the posterior pharynx.

Often, direct inoculation of medium for B pertussis is not possible. In such cases, clinical specimens are placed in Regan Lowe transport medium (half-strength charcoal agar supplemented with horse blood and cephalexin).11,12

Polymerase chain reaction testing: Faster, more sensitive, but less specific

PCR testing of nasopharyngeal specimens is now being used instead of bacterial culture to diagnose pertussis in many situations. Alternatively, nasopharyngeal aspirate (or secretions collected with two Dacron swabs) can be obtained and divided at the time of collection and the specimens sent for both culture and PCR testing. Because bacterial culture is time-consuming and has poor sensitivity, the CDC states that a positive PCR test, along with the clinical symptoms and epidemiologic information, is sufficient for diagnosis.5

PCR testing can detect B pertussis with greater sensitivity and more rapidly than bacterial culture.12–14 Its sensitivity ranges from 61% to 99%, its specificity ranges from 88% to 98%,12,15,16 and its results can be available in 2 to 24 hours.12

PCR testing’s advantage in terms of sensitivity is especially pronounced in the later stages of the disease (as in our patient), when clinical suspicion of pertussis typically arises. It can be used effectively for up to 4 weeks from the onset of cough.14 Our patient, who presented nearly 3 weeks after the onset of symptoms, underwent nasopharyngeal sampling for PCR testing.

However, PCR testing is not as specific for B pertussis as is bacterial culture, since other Bordetella species can cause positive results on PCR testing. Also, as with culture, a negative test does not reliably rule out the disease, especially if the sample is collected late in the course.

Therefore, basing the diagnosis on PCR testing alone without the proper clinical context is not advised: pertussis outbreaks have been mistakenly declared on the basis of false-positive PCR test results. Three so-called “pertussis outbreaks” in three different states from 2004 to 200617 were largely the result of overdiagnosis based on equivocal or false-positive PCR test results without the appropriate clinical circumstances. Retrospective review of these pseudo-outbreaks revealed that few cases actually met the CDC’s diagnostic criteria.17 Many patients were not tested (by any method) for pertussis and were treated as having probable cases of pertussis on the basis of their symptoms. Patients who were tested and who had a positive PCR test did not meet the clinical definition of pertussis according to the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists.17

Since PCR testing varies in sensitivity and specificity, obtaining culture confirmation of pertussis for at least one suspicious case is recommended any time an outbreak is suspected. This is necessary for monitoring for continued presence of the agent among cases of disease, recruitment of isolates for epidemiologic studies, and surveillance for antibiotic resistance.