Goal-directed antihypertensive therapy: Lower may not always be better

ABSTRACTAt least 16 treatment trials have been done in which patients were randomly assigned different blood pressure goals in an attempt to better define specific target pressures. We critically review the data.

KEY POINTS

- Observational data indicate that lower blood pressure is better than higher, and many trials have confirmed that treatment of hypertension is beneficial. Guidelines have set specific goals based on the observational data.

- Surprisingly, randomized controlled trials have not shown a lower target to offer significant clinical benefit, and suggest the potential for harm with overly aggressive therapy.

- The optimal blood pressure on treatment for an individual patient remains unclear.

The Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy (REIN)-2 trial39

Patients: 338 nondiabetic patients who had proteinuria and reduced creatinine clearance.

Treatment and blood pressure goals. All were treated with ramipril and randomized to intensive (< 130/80 mm Hg) vs standard control (diastolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg) with therapy based on felodipine (Plendil).

Results. The study was terminated early because of futility. Despite a mean difference of 4.1 mm Hg systolic and 2.8 mm Hg diastolic, the groups did not differ in the rate of progression to end-stage renal disease (23% with intensive therapy vs 20% with standard therapy) or in the rate of decline of the measured glomerular filtration rate (0.22 vs 0.24 mL/min/1.73 m2/month).

Comment. The internal validity of this study can be questioned because of the low separation of achieved blood pressure and because of its early termination.

No benefit from a lower blood pressure goal in preserving kidney function

To summarize, these trials all showed no significant benefit from either targeting or achieving lower blood pressure in terms of slowing the decline of kidney function. Overall, they do not define a target and offer little support that a lower goal blood pressure is indicated with respect to the rate of loss of glomerular filtration rate in chronic kidney disease.

However, post hoc analysis of the MDRD trial indicates a statistical interaction between targeted blood pressure and degree of baseline proteinuria. At higher levels of proteinuria (≥ 1 g/day), the group with the lower blood pressure target had better outcomes.

In addition, long-term follow-up (mean of 12.2 years) of the AASK trial, including a 7-year cohort phase with nearly similar blood pressures in both groups, also indicated an interaction with targeted blood pressure and baseline proteinuria.40 Although the overall analysis was negative, there was a significant reduction in the primary end point in the group originally assigned the low target when analysis was restricted to those in the highest tertile of proteinuria. These and other data10 suggest that patients with chronic kidney disease and proteinuria may represent a distinct subset of chronic kidney disease patients who benefit from more intensive blood-pressure-lowering. However, patients in the REIN-2 trial34 and the macroalbuminuric patients in the ABCD hypertensive trial35 did not benefit from a lower targeted blood pressure despite significant proteinuria.

FOUR TRIALS WITH CARDIOVASCULAR END POINTS

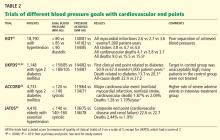

The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial41

Patients: 18,790 patients with diastolic blood pressure between 100 and 115 mm Hg.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Diastolic pressure of equal to or less than 80, 85, or 90 mm Hg.

Results. At an average of 3.8 years, the average blood pressures in the three groups were approximately 140/81, 141/83, and 144/85 mm Hg, respectively. There was no difference between the groups in the rate of the composite primary end point of all myocardial infarctions, all strokes, and cardiovascular death. Any conclusions from this trial were compromised by the small difference in achieved blood pressures between groups.

In the 1,501 patients with diabetes, the incidence of the primary end point was 50% lower with a goal of 80 mm Hg or less than with a goal of 90 mm Hg or less.

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)42,43

Patients: 1,148 hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Either “tight control” (aiming for < 150/85 mm Hg) or “less tight control” (aiming for < 180/105 mm Hg).

Results. At a median follow-up of 8.4 years, the attained blood pressures were 144/82 vs 154/87 mm Hg. The difference produced significant benefits, including a 24% lower rate of any diabetes-related end point, a 32% lower rate of death due to diabetes, and a nonsignificant 18% lower rate of total mortality—all co-primary end points.

The less-tight-control group had many patients with initial blood pressures below 180/105 mm Hg; hence, over 50% of patients received no antihypertensive therapy at the start of the trial. By the end of the trial 9 years later, 20% had still not been treated. This compares with only 5% of patients in the tight-control group who were not treated with antihypertensives throughout the trial. Therefore, this trial serves as better evidence for treating vs not treating, rather than defining a specific goal.

During a 10-year follow-up, blood pressure differences disappeared within 2 years.43 There was no legacy effect, as the significant differences noted during the trial were no longer present 10 years later.

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD)44

Patients: 4,733 patients with type 2 diabetes.

Randomized blood pressure goals. Systolic blood pressure lower than either 120 or 140 mm Hg.

Results. At 4.7 years, despite a significant difference in mean systolic blood pressure of 14.2 mm Hg after the first year (119.3 vs 133.5 mm Hg), there was no difference in the primary end point of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death. There were fewer strokes in the lower-pressure group but no difference in myocardial infarctions, which were five times more common than strokes. Serious adverse events attributed to antihypertensive treatment occurred more frequently in the intensive-therapy group (3.3% vs 1.3%, P < .001).

Comment. There were fewer events than expected, possibly limiting the trial’s ability to detect a statistical difference. Compared with both the UKPDS and the diabetic population of HOT, ACCORD is much larger and more internally valid (unlike in UKPDS, nearly all patients in both groups were treated, and compared with HOT there was much greater separation of achieved pressure). It is more recent and better reflects current overall practice. It indicates that when specifically aiming for a target blood pressure, lower is not always better and comes at a price (more severe adverse events).