Heart failure in frail, older patients: We can do ‘MORE’

ABSTRACTA comprehensive approach is necessary in managing heart failure in frail older adults. To provide optimal care, physicians need to draw on knowledge from the fields of internal medicine, geriatrics, and cardiology. The acronym “MORE” is a mnemonic for what heart failure management should include: multidisciplinary care, attention to other (ie, comorbid) diseases, restrictions (of salt, fluid, and alcohol), and discussion of end-of-life issues.

KEY POINTS

- Not only does heart failure itself result in frailty, but its treatment can also put additional stress on an already frail patient. In addition, the illness and its treatments can negatively affect coexisting disorders.

- Common signs and symptoms of heart failure are less specific in older adults, and atypical symptoms may predominate.

- Age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics must be taken into account when prescribing drugs for heart failure.

- Effective communication among health professionals, patients, and families is necessary.

- Given the life-limiting nature of heart failure in frail older adults, it is critical for clinicians to discuss end-of-life issues with patients and their families as soon as possible.

THE BROKEN HEART

In 2005, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association defined congestive heart failure as “a complex clinical syndrome that can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood.”9 This characterization captures the intricate nature of the disease: its spectrum of symptoms, its many causes (eg, coronary artery disease, hypertension, nonischemic or idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and valvular heart disease), and the dual pathophysiologic features of systolic and diastolic impairment.

Systolic vs diastolic failure

Of the various ways of classifying heart failure, the most important is systolic vs diastolic.

The hallmark of systolic heart failure is a decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, and it is characterized by a large thin-walled ventricle that is weak and unable to eject enough blood to generate a normal cardiac output.

In contrast, the ejection fraction is normal or nearly normal in diastolic heart failure, but the end-diastolic volume is decreased because the ventricle is hypertrophied and thick-walled. The resultant chamber has become small and stiff and does not have enough volume for sufficient cardiac output.

QUIRKS IN THE HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The combination of inactivity and coexisting illnesses in a frail older adult may obscure some of the usual clinical manifestations of heart failure. While shortness of breath on mild exertion, easy fatigability, and leg swelling are common in younger heart failure patients, these symptoms may be due to normal aging in a much older patient. Let us consider some important aspects of the common signs and symptoms associated with heart failure.

Dyspnea on exertion is one of the earliest and most prominent symptoms. The usual question asked of patients to elicit whether this key manifestation is present is, “Do you get short of breath after walking a block?” However, this question may not be appropriate for a frail elderly person whose activity is restricted by comorbidities such as severe arthritis, coronary artery disease, or peripheral arterial disease. For a patient like this, ask instead if he or she gets short of breath after milder forms of exertion, such as making the bed, walking to the bathroom, or changing clothes.10 Also, keep in mind that dyspnea on exertion may be due to other conditions, such as renal failure, lung disease, depression, anemia, or deconditioning.

Orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea may not be volunteered or elicited if a patient is sleeping in a chair or a recliner.

Leg swelling is less specific in older adults than in younger patients because chronic venous insufficiency is common in older people.

Weight gain almost always accompanies symptomatic heart failure but may also be due to increased appetite secondary to depression.

A change in mental status is common in elderly people with heart failure, especially those with vascular dementia with extensive cerebrovascular atherosclerosis or those who have latent Alzheimer disease.10

Cough, a symptom of a multitude of disorders, may be an early or the only manifestation of heart failure.

Pulmonary crackles are typically detected in most heart failure patients, but they may not be as characteristic in older adults, as they may also be noted in bronchitis, pneumonia, and other chronic lung diseases.

Additional symptoms to watch for include fatigue, syncope, angina, nocturia, and oliguria.

The bottom line is to integrate individual findings with other elements of the history and physical examination in diagnosing heart failure and tracking its progression.

CLINCHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Congestive heart failure is essentially a clinical diagnosis best established even before ordering tests, especially during times and situations in which these tests are not always readily available, such as outside office hours and in a long-term care setting.

A reliable and thorough history and physical examination is the most important component of the diagnostic process.

An echocardiogram is obtained next to measure the ejection fraction, which has both prognostic and therapeutic significance. Echocardiography can also uncover potential contributory cardiac structural abnormalities.

A chest radiograph is also typically obtained to look for pulmonary congestion, but in older adults its interpretation may be skewed by chronic lung disease or spinal deformities such as scoliosis and kyphosis.

The B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level is a popular blood test. BNP is commonly elevated in patients with heart failure. However, an elevated level in older adults should always be evaluated within the context of other clinical findings, as it can also result from advancing age and diseases other than heart failure, such as coronary artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, pulmonary embolism, and renal insufficiency.11,12

PHARMACOTHERAPY PEARLS

Drug treatment for heart failure has evolved rapidly. Robust and sophisticated clinical trials have led to guidelines that call for specific medications. Unfortunately, older patients, particularly the very old and frail, have been poorly represented in these studies.9 Nonetheless, the type and choice of drugs for the young and old are similar.

Take into account age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics

Age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics must be taken into account when prescribing drugs for heart failure.13

Oral absorption of cardiovascular drugs is not significantly affected by the various changes that occur in older adults (eg, reduced gastric acid production, gastric emptying rate, gastrointestinal blood flow, and mobility). However, reductions in both lean body mass and total body water that come with aging result in lower volumes of distribution and higher plasma concentrations of hydrophilic drugs, most notably angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and digoxin. In contrast, the plasma concentrations of lipophilic drugs such as beta-blockers and central alpha-agonists tend to decrease as the proportion of body fat increases in older adults.

As the plasma albumin level diminishes with age, the free-drug concentration of salicylates and warfarin (Coumadin), which are extensively albumin-bound, may increase.

The serum concentrations of cardiovascular drugs metabolized in the liver—eg, propranolol (Inderal), lidocaine, labetalol (Trandate), verapamil (Calan), diltiazem (Cardizem), nitrates, and warfarin—may be elevated due to reduced hepatic blood flow, mass, volume, and overall metabolic capacity.

Declines in renal blood flow, glomerular filtration, and tubular function may cause accumulation of drugs that are excreted through the kidneys.

Beware of toxicities

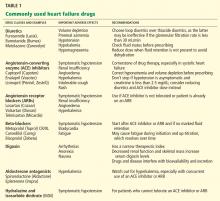

Table 1 lists some of the drugs used in treating heart failure, common adverse affects to watch for, and recommendations for their use.