Biomedical engineering in heart-brain medicine: A review

ABSTRACT

New reports have emerged exploring the use of electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves in patients for the treatment of depression, heart failure, and hypertension. Abolishing renal sympathetic nerve activity in resistant hypertension has also been described. Since nerve bundles carry a variety of signals to multiple organs, it is necessary to develop technologies to stimulate or block targeted nerve fibers selectively. Mathematical modeling is a major tool for such development. Purposeful modeling is also needed to quantitatively characterize complex heart-brain interactions, allowing an improved understanding of physiological and clinical measurements. Automated control of therapeutic devices is a possible eventual outcome.

NEURAL INTERVENTIONS

A second and complementary way in which bioengineering can contribute to heart-brain medicine is through the development and evaluation of technology that applies selective electrical, chemical, or mechanical stimulation to the physiological system. External interventions may have therapeutic effects even though the underlying physiological mechanisms are not fully understood. For example, deep brain electrical stimulation is increasingly used or explored to treat epilepsy, Parkinson disease, and depression.18,19 The development of technology to deliver drugs locally is advancing rapidly and is almost certain to play a major role in exploring heart-brain interactions. The remainder of this paper concentrates on interventions applied through peripheral nerves.

Vagal stimulation

Vagal stimulation is being used to treat epilepsy, but now it is also being explored for the treatment of drug-resistant depression and chronic migraine.20,21 The intensity, frequency, pulse width, and train duration of the apparently single-channel stimulation are set telemetrically. Preliminary data indicate a long-term success rate of about 20% for depression20 and improvement in 2 of 4 patients with chronic migraine.21 Side effects include discomfort caused by the electrical stimulation and vocalization impairments.

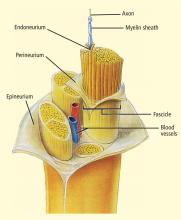

The selective stimulation of nerves has received much attention in rehabilitation engineering since electrical activation of peripheral motor fibers can restore at least some function in patents with spinal cord injury. The stimulation must be selective: different muscles to restore movement need to contract in the appropriate sequence and with appropriate intensity. Thus, fascicles of motor nerves innervating these muscles must be stimulated accordingly.

Electrodes have been developed in a variety of configurations for selectively activating the desired fibers in a nerve bundle.22 Multiple electrodes around the nerve allow targeting of the desired fascicles and preferential stimulation of small nerve fibers.23,24 Gently compressing the nerve using a flat electrode sleeve enhances selectivity by increasing the surface area of the stimulated nerve.25 A tripolar sleeve electrode along the nerve (one cathode at the middle and an anode on each side) may be used to preferentially stimulate small fibers by “anodal blockade” of the propagation of activity in large fibers.26 Mathematical models of nerve excitation, combined with models of the tissue surrounding the nerve fibers, show that positioning the anodes at different distances from the cathode can generate unidirectional propagation.27 Mathematical analysis also shows that the stimulating pulse should have a slowly decaying trailing edge to assure effectiveness of the blockade.27,28

Similar technologies are likely necessary for stimulating the vagus for specific purposes. If the goal is to induce central effects, appropriate afferents should be stimulated. If the goal is to influence the heart directly, cardiac vagal efferents need to be stimulated without confounding the effect by also stimulating afferents. Since cardiac efferent fibers are small and constitute only a small portion of vagal trunk,3 their stimulation requires special care to reverse the normal “largest first” recruitment of stimulated fibers.

The recently reported first pilot study of vagal stimulation in heart failure patients used an electrode that seems to partially satisfy such requirements.29,30 Although the details appear to be proprietary, the implantable electrical stimulator has multiple electrodes and induces anodal blockade to preferentially stimulate efferent rather than afferent nerve fibers.

In the pilot study, 8 patients received intermittent vagal stimulation (2 to 10 sec “on” and 6 to 30 sec “off”) of the right cervical vagus using a pulse delivered 70 msec after each R wave of the ECG. The stimulating current, limited by a threshold or the onset of side effects, was adjusted to achieve a heart rate reduction of 5 to 10 beats/min. Patients were evaluated up to 6 months; no permanent side effects were reported. There was a modest improvement of cardiac function as judged by a reduction in left ventricular volumes, as well as a clear improvement in a measure of quality of life. The study shows feasibility and suggests further investigations.

The primary task seems to be optimization of stimulation parameters. Since natural vagal impulses are distributed through the cardiac cycle,3 artificial stimulation might be more effective if it emulated the natural firing pattern. Since long-term heart rate reduction was minimal, parameters might be tuned further to stimulate small cardiac efferent fibers that may be far from the electrodes. Measurements of heart rate variability during controlled conditions may reveal the pacemaker’s responsiveness to vagal stimulation. Comparison of duty cycles (duration of “on” and “off”) may show whether the study’s choice, to some extent already mimicking the breathing-induced modulation of natural vagal activity, is most effective. Such studies to optimize effectiveness may be best performed in chronically instrumented animals.

Baroreceptor stimulation

An extensively studied mechanism that modulates the autonomic nervous system is the baroreceptor reflex that is known to be depressed in heart failure. Former efforts to use this reflex therapeutically were recently revived in both animal experiments and human studies.31 For example, bilateral carotid sinus stimulation nearly doubled the survival time of dogs with pacing-induced heart failure.32 Although measures of left ventricular function, obtained while the stimulator was turned off, were similar in dogs with stimulated and unstimulated carotid sinuses, plasma norepinephrine was lower in the animals receiving stimulation. This suggests that carotid sinus stimulation led to a general decrease in sympathetic activation. It is noteworthy that the stimulation was applied intermittently (9 min “on”, 1 min “off”) to avoid the resetting (or adaptation) of baroreceptors, a phenomenon that had led to the now-doubted traditional belief that the baroreflex regulates only acute rather than long-term changes of blood pressure.2

Chronic bilateral baroreceptor stimulation was also applied in 21 patients with essential hypertension that could not be controlled by medication.33 Measurements were taken 1 month after implantation with the stimulator turned off and 3 months after chronic stimulation with the stimulator on. Stimulation moderately reduced both blood pressure and heart rate; heart rate variability suggested an increase in parasympathetic activity and a decrease in sympathetic activity.

Renal sympathetic ablation

Technology-based approaches encompass not only the stimulation of nerves but also the abolition of nerve activity. In an exploratory study, bilateral sympathetic denervation was performed in 45 patients with drugresistant hypertension.34 A catheter, introduced through the femoral artery, was positioned at the entrance of each renal artery. Sympathetic denervation was produced by radiofrequeny energy applied for a maximum of 2 minutes. The details of the technology appear proprietary, complete ablation could not be ascertained, and both efferents and afferents are likely to have been stimulated. Nevertheless, the procedure appeared safe and resulted in a significant reduction in both diastolic and systolic pressures over 12 months. In addition to lowering blood pressure, catheter-based sympathetic denervation might also prove therapeutic in heart failure and chronic kidney disease.