Case studies and clinical considerations in menopausal management

The challenge of educating younger doctors about HT

Dr. Thacker: I think we need to find ways to translate the data on HT to younger generations of physicians, because the closer one is to graduating from medical school, the less likely he or she is to offer HT to an otherwise healthy, severely symptomatic woman younger than age 60.

Dr. McKenzie: Absolutely, and I think the real challenge is to reach younger physicians who go into private practice, who generally have the fewest opportunities to stay on top of the latest evidence. We must offer evidence-based education programs on this topic to physicians in the community to ensure that they are equipped to understand and explain the real risks and benefits of HT in order to individualize treatment decisions.

As a physician at a tertiary care center, I am surprised at the number of women referred to me who should have already been on HT for menopausal symptoms, but their physicians were unduly influenced by the initial WHI publication. They need to thoroughly evaluate their patients, assess their risks, assess any new medical problems, try to educate them, and then tailor therapy to improve their patients’ quality of life.

Correcting misperceptions: WHI was not a treatment trial

Dr. Thacker: I believe that many practitioners and especially students do not realize that the WHI was a trial designed to assess prevention of chronic diseases. It was not a menopausal treatment trial, and often its data are being misapplied to women who are different from the ones enrolled in the WHI, in that they are younger and more symptomatic.

Dr. Gass: It is correct that the WHI was not a treatment trial, but that was how HT was being used by some physicians and patients prior to the WHI. Physicians in this country were giving some 65-year-old women HT for osteoporosis and dementia. These practices needed to be supported with data, and that was the impetus behind the trial. Along the same lines, it is important how we present the risks to patients. If HT is being used as a therapy for a woman suffering from menopausal symptoms, she might be willing to accept more risk than if it is being used like a vitamin pill, to promote general health, in which case the risks should be virtually nil because the woman is healthy and without complaints.

Dr. Thacker: Yes, and that is why I think the earlier discussion of comparable risks of breast cancer, stroke, and VTE with aspirin, SERMs, fibric acid derivatives, and statins helps to put the risks of HT in perspective. It appears that physicians and patients tolerate very similar risks with commonly used nonhormonal medicines in women but do not tolerate any risks with HT, even in symptomatic women. In my opinion, this is a medical travesty. It is important to recognize that there are few absolutes in medicine that apply to all patients. The only universal recommendations I make to all patients are to wear seatbelts and not to smoke.

Dr. Hodis: What I find notable is that with HT we see a reduction in mortality regardless of the risks that we have described. As the observational data show, if we start HT and continue it, there is a reduction in mortality of 30% or even greater, and the clinical trial data tend to support this benefit. So why do we shy away from HT? Because we are worried about a small increase in breast cancer diagnoses or a small increase in DVT? That is an issue I am grappling with.

Dr. Thacker: Similarly, how do you reconcile the observational data with aspirin? In the Nurses’ Health Study, the aspirin users had lower mortality, but in all of the randomized controlled trials in midlife women, we do not see a reduction in cardiovascular risk with aspirin, let alone a reduction in mortality. So, the people who self-select for treatment are obviously different from those enrolled in randomized trials. The randomized controlled trial may be our gold standard, but it is not necessarily the only evidence to consider.

Dr. Hodis: But there is a concordance between observational studies and randomized trials with respect to overall mortality and HT. The data from a meta-analysis of 30 randomized trials8 are consistent with the data from observational studies, even though they do identify risks. I wonder how many more women would select HT if we told them about the 30% reduction in mortality despite the possibility of breast cancer diagnosis and DVT risks.

Dr. Gass: Women will select according to their own agenda.

Dr. Hodis: Yes, in the end, it is all individualized.

Dr. Gass: Indeed, because women have specific concerns, such as breast cancer, fracture risk, or Alzheimer disease, and they base their personal decisions on these specific concerns. I educate them about the risks and benefits, and they pretty much decide for themselves. They know their priorities.

Age and the risk-benefit assessment with HT

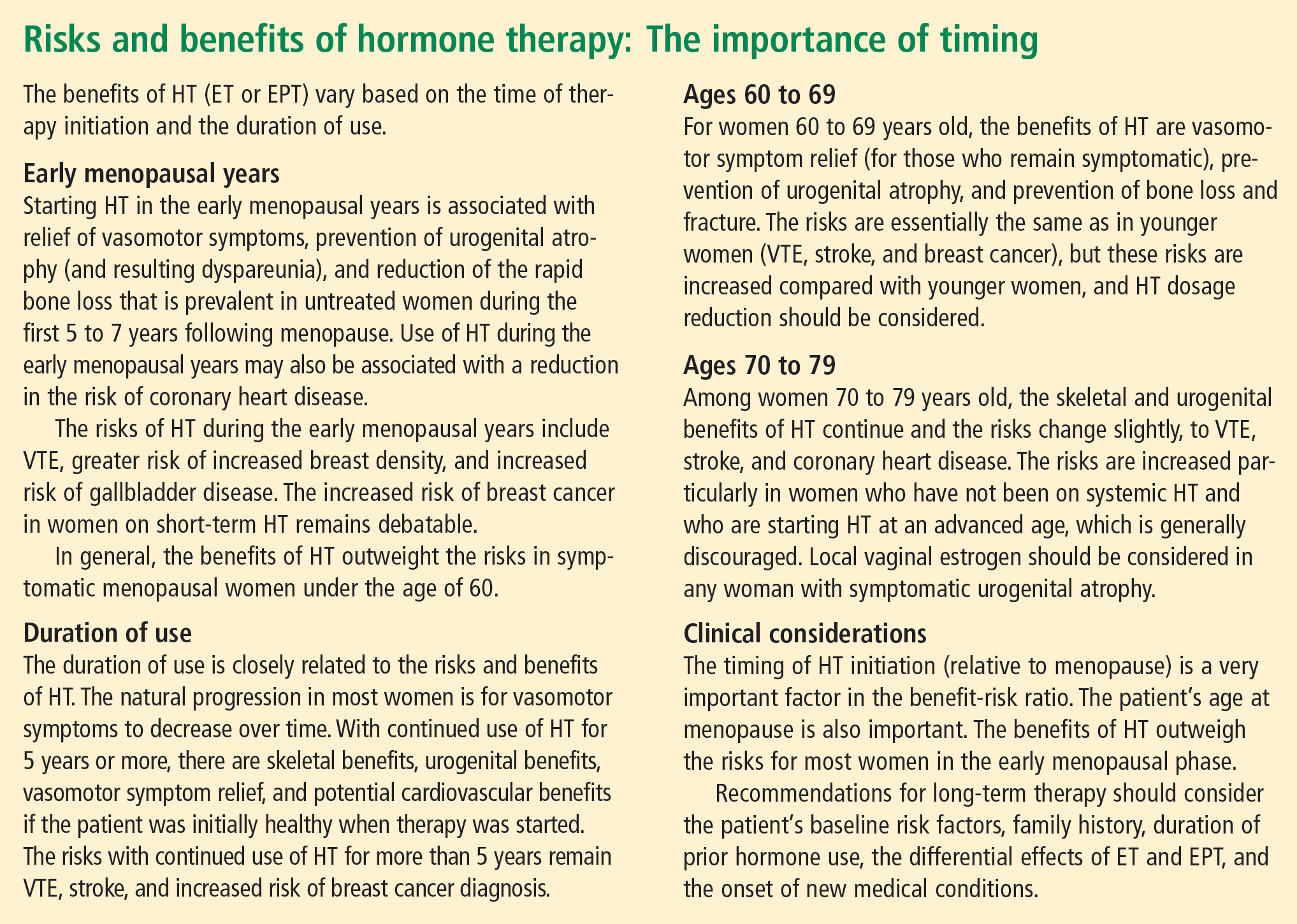

Dr. Thacker: Does the panel have any comments on the recent position statement from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists concluding that the benefits of HT exceed the risks in symptomatic women younger than age 60?

Dr. Hodis: My only comment is to ask why it took them so long to come to that conclusion.

Dr. Thacker: We could say the same for the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). It was not until its 2007 position statement on the use of ET and EPT in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women that NAMS moved beyond the issue of a time limit for HT—the “lowest dose for the shortest amount of time” mantra—and recommended the type of reevaluation used with any other treatment.

It seems as if practitioners are less willing to tolerate the risks of HT in older women than to tolerate the risks of hormonal contraceptives in younger women. Perhaps that is because hormonal contraceptives prevent pregnancy and the risks associated with it, yet this same value is not afforded to the symptoms and other effects suffered by postmenopausal women. I think we did afford HT similar value as hormonal contraceptives in the 1980s and 1990s, when we were trying to promote the potential health benefits of HT before we had bisphosphonates and statins and before we realized the risks of VTE with HT, risks that were identified much sooner with hormonal contraceptives. Since then the medical community has overcorrected by too often dismissing HT, overemphasizing the risks and ignoring very important quality-of-life issues, including sex and sleep disturbances, in the process.

Dr. Jenkins: Also, too many people associate menopause only with hot flashes, without taking into account the increased risk of serious diseases that may occur at this time, such as osteoporosis and heart disease.

Dr. Thacker: That may be because menopause is a normal event. It can be a great time of life for many women; in fact, it is associated with lower rates of depression, unless there is a prolonged symptomatic perimenopause. Menopause is certainly not a disease, and NAMS has been very good at recognizing and promoting it as a normal phase of life. But to neglect treating a woman going through menopausal symptoms just because menopause is a normal life event would be akin to withholding assistance for women during childbirth, which is another natural event.

We fail from a medical perspective if we do not take care of symptomatic women, because they will then turn to people who are not physicians and who offer unregulated therapies. These people may deliver the right message—that menopausal women deserve to feel well and look good—but the way they tell women to treat menopausal symptoms is not science-based.

At one time, we were overtreating women and not individualizing therapy, but to me it is even more worrisome to withhold therapies unless women are so highly symptomatic that they consider ending their life. We are continuing to discover the risks and benefits of HT and how to further tailor it. We have many newer, lower-dose HT options, and we are expecting the first nonhormonal therapy for menopausal vasomotor symptoms, desvenlafaxine. We are fortunate to have bone agents and local vaginal therapies for women without vasomotor symptoms. With both hormonal and nonhormonal options, we must keep the risks and benefits of any therapy in perspective.

CONCLUSIONS

Dr. Thacker: This has been a great discussion, and although we do not all agree on every point, I would like to conclude by summarizing some key points on which I think we do all agree (see sidebar above). Menopause is a normal life event, but for some women who are symptomatic, and for a smaller percentage who will be symptomatic for the rest of their lives, HT is the gold standard, although it does not treat all symptoms and has some well-defined risks. We do have other options on the horizon for relief of vasomotor symptoms, for bone health, and for urogenital atrophy.

Following the data on the effects of HT on cardiovascular health will be particularly interesting. Although there is not support for using HT specifically for cardiovascular prevention, there are provocative data that in the symptomatic woman who has self-selected it, HT has cardiovascular benefit and reduces the risk of diabetes.

A woman on HT who has not had “early harm” does not need to arbitrarily discontinue therapy based on any time limit, as long as she is being periodically reevaluated and is offered individualized options.