Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the cancer surgery patient

ABSTRACT

Cancer patients, especially those undergoing surgery for cancer, are at extremely high risk for developing venous thromboembolism (VTE), even with appropriate thromboprophylaxis. Anticoagulant prophylaxis in cancer surgery patients has reduced the incidence of VTE events by approximately one-half in placebo-controlled trials, and extended prophylaxis (for up to 1 month) has also significantly reduced out-of-hospital VTE events in clinical trials in this population. Clinical trials show no difference between low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and unfractionated heparin in VTE prophylaxis efficacy or bleeding risk in this population, although the incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is lower with LMWH. The risk-benefit profile of low-dose anticoagulant prophylaxis appears to be favorable even in many cancer patients undergoing neurosurgery, for whom pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis has been controversial because of bleeding risks.

GUIDELINES FOR VTE PROPHYLAXIS IN THE CANCER SURGERY PATIENT

American College of Chest Physicians

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recently published clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolic disease in cancer patients.35 The defined at-risk population for these guidelines is the adult cancer inpatient with a diagnosis of (or clinical suspicion for) cancer. The guidelines recommend prophylactic anticoagulation (category 1 recommendation) with or without a sequential compression device as initial prophylaxis, unless the patient has a relative contraindication to anticoagulation, in which case mechanical prophylaxis (sequential compression device or graduated compression stockings) is recommended. (A category 1 recommendation indicates “uniform NCCN consensus, based on high-level evidence.”)

The NCCN guidelines include a specific recommended risk-factor assessment, which includes noting the patient’s age (VTE risk increases beginning at age 40 and then steeply again at age 75), any prior VTE, the presence of familial thrombophilia or active cancer, the use of medications associated with increased VTE risk (chemotherapy, exogenous estrogen compounds, and thalidomide or lenalidomide), and a number of other risk factors for VTE as outlined in the prior two articles in this supplement. The NCCN guidelines explicitly call for assessment of modifiable risk factors for VTE (ie, smoking or other tobacco use, obesity, and a low level of activity or lack of exercise) and call for active patient education on these factors.

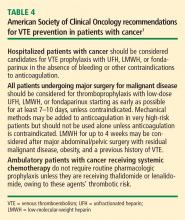

American Society of Clinical Oncology

Our recommended algorithm

LINGERING CHALLENGE OF UNDERUTILIZATION

Despite this consensus on ways to reduce thromboembolic risk in this population and the clear evidence of the benefit of VTE prophylaxis in patients with cancer, data from several registries confirm a persistently low utilization of prophylaxis in patients with cancer.36–38 The global Fundamental Research in Oncology and Thrombosis (FRONTLINE) study surveyed 3,891 clinicians who treat cancer patients regarding their practices with respect to VTE in those patients.36 The survey found that only 52% of respondents routinely used thromboprophylaxis for their surgical patients with cancer. More striking, however, was the finding that most respondents routinely considered thrombo-prophylaxis in only 5% of their medical oncology patients. These data are echoed by findings of other retrospective medical record reviews in patients undergoing major abdominal or abdominothoracic surgery (in many cases for cancer), with VTE prophylaxis rates ranging from 38% to 75%.37,38

SUMMARY

Patients undergoing surgery for cancer have an increased risk of VTE and fatal PE, even when thromboprophylaxis is used. Nevertheless, prophylaxis with either LMWH or UFH does reduce venographic VTE event rates in these patients. If UFH is chosen for prophylaxis, a three-times-daily regimen should be used in this population. In specific surgical cancer populations, especially those undergoing abdominal surgery, out-of-hospital prophylaxis with once-daily LMWH is warranted. Current registries reveal that compliance with established guidelines for VTE prophylaxis in this population is low.