Helping children and adults with hypnosis and biofeedback

ABSTRACT

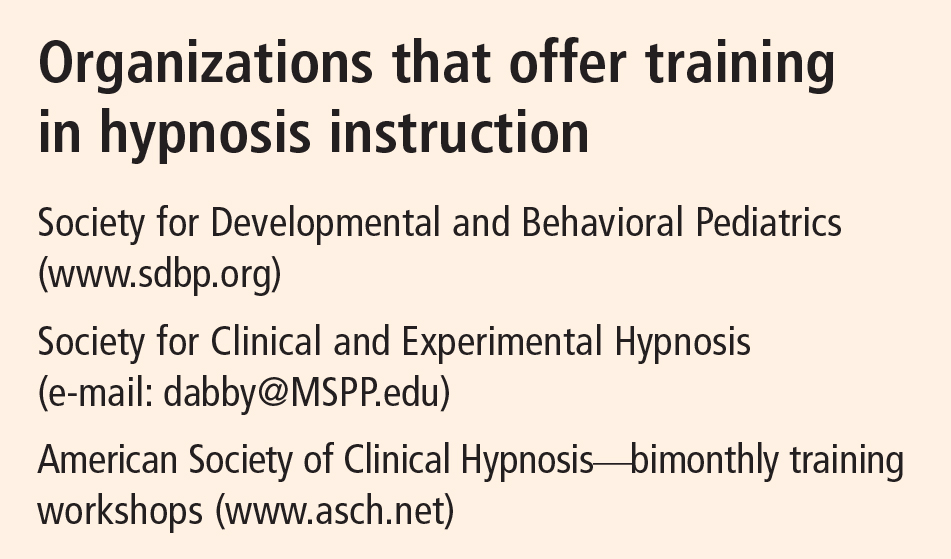

Hypnosis and biofeedback are cyberphysiologic strategies that enable subjects to develop voluntary control of certain physiologic processes for the purpose of improving health. Self-hypnosis has been used with and without biofeedback for a wide range of therapeutic applications, and both laboratory studies and clinical trials have shown it to be effective in improving symptoms and outcomes in various disorders. More formal Cochrane reviews of hypnotherapeutic interventions are currently under way. Thorough patient assessment should precede training in self-hypnosis in order to properly tailor training strategies to patient preferences and characteristics, especially for children. Workshops offered by various clinical societies are available to train health professionals in self-hypnosis.

CONCURRENT USE OF BIOFEEDBACK AND HYPNOSIS

Much common ground exists between hypnosis and biofeedback. Both have the potential to provide a powerful validation of mind–body links, contribute to a lowered state of sympathetic arousal, heighten awareness of internal events and sensations, facilitate imagery abilities, narrow the focus of attention, and enhance the internal locus of control.

Adding biofeedback games to self-hypnosis training can make the experience much more interesting for children. Children see evidence on the screen that, by changing their thinking, they have control over a body response such as skin temperature, electrodermal activity, or pulse rate variability. Adults also benefit from the addition of biofeedback to self-hypnosis training. A patient cannot effect a change in a biofeedback response without a change in his or her mental imagery.

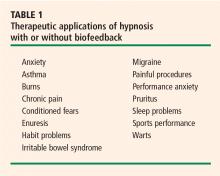

A WIDE RANGE OF THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS

Hypnosis training is valuable as a primary intervention for prevention of juvenile migraine8,9 as well as for many performance problems (eg, fear of public speaking or playing tennis), insomnia, and many habit problems (eg, nail-biting, tics, hair-pulling). For treatment of juvenile warts, hypnosis is at least as effective as topical treatment and associated with fewer relapses.10

Hypnosis is valuable as an adjunctive intervention during painful procedures,11–13 and many adults and children use self-hypnosis to teach themselves to be comfortable through procedures without any pharmacologic treatment.14

Training in self-hypnosis is a valuable adjunct for both children and adults with chronic illnesses such as cancer, cardiac failure, asthma, hemophilia, sickle cell disease, and arthritis. Self-hypnosis helps to reduce anxiety and increase comfort, and it provides a therapeutic tool over which the patient has control. Several recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of hypnosis in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.15

Hypnosis and cardiac disease

With respect to cardiac disease, training in hypnosis can help to reduce symptoms both preoperatively and postoperatively, to enhance the success of rehabilitation following myocardial infarction, and to reduce anxiety associated with chronic heart disease.16

Hypnosis also is helpful for motivating behaviors associated with prevention of cardiac disease, such as regular exercise, eating a low-fat diet, and smoking cessation. Several studies have found hypnosis to be a helpful adjunct to cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of obesity.17 Additionally, a number of studies have demonstrated that hypnosis is useful as an initial intervention for smoking cessation,18 although only about 45% of persons who stop smoking with hypnosis continue to abstain 6 months later. In the case of both obesity and smoking cessation, hypnosis has modestly better efficacy compared with other treatments for these conditions.

TEACHING SELF-HYPNOSIS: SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS WITH CHILDREN

Self-hypnosis has great potential in children, as children delight in recognizing their own control over problems such as bed-wetting or wheezing or test anxiety.

As noted above, success with hypnosis requires that the patient practice self-hypnosis daily. In the case of children, it is essential that the coach or teacher emphasize that the child is in control and can decide when and where to use self-hypnosis. The message should be that self-hypnosis belongs to the child and that he or she needs to practice to become more skilled (as with learning soccer or some other sport), but that no one can force him or her to practice.

The choice of strategies for teaching self-hypnosis varies depending on the child’s age and developmental stage. As children mature, their cognitive abilities change. Preschool children are concrete in their thinking, so therapists working with children of this age must select words carefully. Children between ages 2 and 5 years spend a great deal of their time in various types of behavior based on imagination and fantasy. They enjoy stories and may enter a hypnotic state as a parent or teacher reads a story to them. Unlike adults, they often prefer to practice their self-hypnosis with their eyes open. Although adolescents may enjoy learning self-hypnosis methods that are similar to those preferred by adults, immature adolescents may prefer methods that also appeal to younger children. A child with cognitive impairment can learn self-hypnosis if the therapist selects a teaching approach appropriate for the child’s actual developmental stage. Because of developmental changes, a child of 9 years is unlikely to enjoy a method he or she was taught at age 4. Therapists who work with children should be familiar with a variety of hypnosis induction strategies and be capable of creative modification to accommodate a child’s changing developmental circumstances.19,20

HYPNOSIS RESEARCH WITH CHILDREN

Most subsequent research has consisted of clinical studies documenting the efficacy of hypnosis with children in areas such as pain management, habit problems, wart reduction, and performance anxiety. A recent study completed in Cleveland, Ohio, taught stress-reduction methods, including self-hypnosis, to 8-year-old schoolchildren.30 This study concluded that a short daily stress-management intervention delivered in the classroom setting in elementary school can decrease feelings of anxiety and improve a child’s ability to relax. Many of the children in the study continued to use self-hypnosis in their daily lives after the study was completed.

A host of variables complicate research design

The variability in preferences, learning styles, and developmental stages among children complicates the design of research protocols for studying hypnosis in children. These protocols are often written to describe identical hypnotic inductions, often tape-recorded, to be used at prescribed times. Measured variables do not include whether or not a child likes the induction, listens to the tape, or focuses on entirely different mental imagery of his or her own choosing. Learning disabilities, such as auditory processing handicaps, may interfere with children’s ability to learn and remember self-hypnosis training. Furthermore, learning disabilities are often subtle and may not be recognized without detailed testing.

Each of these variables complicates efforts to perform meta-analyses of hypnosis and related interventions. Analyses of studies on the efficacy of hypnosis in children should include all strategies that induce hypnosis in children—eg, visual imagery, guided imagery, and/or progressive relaxation. Some research studies that are defined as controlled nevertheless mix different therapeutic interventions. An example would be a comparison of hypnosis with guided imagery.

The International Society of Hypnosis is currently sponsoring Cochrane reviews of hypnotherapeutic interventions, including those with children.