What is the role of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin?

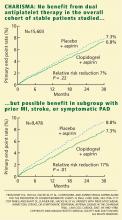

ABSTRACTThe Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) study (N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1706–1717, J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:1982–1988) assessed the effect of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel (Plavix) and aspirin in patients at risk of atherothrombotic events. At a median of 28 months, the rate of the primary efficacy end point (a composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death from cardiovascular causes) was not significantly lower in the group receiving clopidogrel plus aspirin than in the group receiving placebo plus aspirin. However, one subgroup may have derived some benefit from the combination: those at higher risk owing to a history of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease.

KEY POINTS

- Platelets are key players in atherothrombosis, and antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin and clopidogrel prevent events in patients at risk.

- In studies leading up to CHARISMA, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin was found to be beneficial in patients with acute coronary syndromes and in those undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions.

- Clopidogrel should not be combined with aspirin as a primary preventive therapy (ie, for people without established vascular disease). How dual antiplatelet therapy should be used as secondary prevention in stable patients needs further study.

OVERALL, NO BENEFIT

The rates of the secondary end point were 16.7% vs 17.9% (absolute risk reduction 1.2%; relative risk reduction 8%; P = .04).

Possible benefit in symptomatic patients

In a prespecified analysis, patients were classified as being “symptomatic” (having documented cardiovascular disease, ie, coronary, cerebrovascular, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease) or “asymptomatic” (having multiple risk factors without established cardiovascular disease).1

In the symptomatic group (n = 12,153), the primary end point was reached in 6.9% of patients treated with clopidogrel vs 7.9% with placebo (absolute risk reduction 1.0%; relative risk reduction 13%; P = .046). The 3,284 asymptomatic patients showed no benefit; the rate of the primary end point for the clopido-grel group was 6.6% vs 5.5% in the placebo group (P = .20).

In a post hoc analysis, we examined the data from 9,478 patients who were similar to those in the CAPRIE study (ie, with documented prior myocardial infarction, prior ischemic stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease). The rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was 8.8% in the placebo-plus-aspirin group and 7.3% in the clopidogrel-plus-aspirin group (absolute risk reduction 1.5%; relative risk reduction 17%; P = .01; Figure 1).2

HOW SHOULD WE INTERPRET THESE FINDINGS?

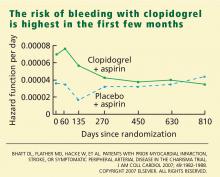

CHARISMA was the first trial to evaluate whether adding clopidogrel to aspirin therapy would reduce the rates of vascular events and death from cardiovascular causes in stable patients at risk of ischemic events. As in other trials, the benefit of clopidogrel-plus-aspirin therapy was weighed against the risk of bleeding with this regimen. How are we to interpret the findings?

- In the group with multiple risk factors but without clearly documented cardiovascular disease, there was no benefit—and there was an increase in moderate bleeding. Given these findings, physicians should not prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy for primary prevention in patients without known vascular disease.

- A potential benefit was seen in a prespecified subgroup who had documented cardiovascular disease. Given the limitations of subgroup analysis, however, and given the increased risk of moderate bleeding, this positive result should be interpreted with some degree of caution.

- CHARISMA suggests that there may be benefit of protracted dual antiplatelet therapy in stable patients with documented prior ischemic events.

A possible reason for the observed lack of benefit in the overall cohort but the positive results in the subgroups with established vascular disease is that plaque rupture and thrombosis may be a precondition for dual antiplatelet therapy to work.

Another possibility is that, although we have been saying that diabetes mellitus (one of the possible entry criteria in CHARISMA) is a “coronary risk equivalent,” this may not be absolutely true. Although it had been demonstrated that patients with certain risk factors, such as diabetes, have an incidence of ischemic events similar to that in patients with prior MI and should be considered for antiplatelet therapy to prevent vascular events,32 more recent data have shown that patients with prior ischemic events are at much higher risk than patients without ischemic events, even if the latter have diabetes.33,34

- The observation in CHARISMA that the incremental bleeding risk of dual antiplatelet therapy vs aspirin does not persist beyond a year in patients who have tolerated therapy for a year without a bleeding event may affect the decision to continue clopidogrel beyond 1 year, such as in patients with acute coronary syndromes or patients who have received drug-eluting stents.35,36

- Another important consideration is cost-effectiveness. Several studies have analyzed the impact of cost and found clopidogrel to be cost-effective by preventing ischemic events and adding years of life.37,38 A recent analysis from CHARISMA also shows cost-effectiveness in the subgroup of patients enrolled with established cardiovascular disease.39 Once clopidogrel becomes generic, the cost-effectiveness will become even better.

Further studies should better define which stable patients with cardiovascular disease should be on more than aspirin alone.