Syncope: Etiology and diagnostic approach

ABSTRACTThere are three major types of syncope: neurally mediated (the most common), orthostatic hypotensive, and cardiac (the most worrisome). Several studies have shown a normal long-term survival rate in patients with syncope who have no structural heart disease, which is the most important predictor of death and ventricular arrhythmia. The workup of unexplained syncope depends on the presence or absence of heart disease: electrophysiologic study if the patient has heart disease, tilt-table testing in those without heart disease, and prolonged rhythm monitoring in both cases if syncope remains unexplained.

KEY POINTS

- Neurally mediated forms of syncope, such as vasovagal, result from autonomic reflexes that respond inappropriately, leading to vasodilation and relative bradycardia.

- Orthostatic hypotension is the most common cause of syncope in the elderly and may be due to autonomic dysfunction, volume depletion, or drugs that block autonomic effects or cause hypovolemia, such as vasodilators, beta-blockers, diuretics, neuropsychiatric medications, and alcohol.

- The likelihood of cardiac syncope is low in patients with normal electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings.

- Hospitalization is indicated in patients with syncope who have or are suspected of having structural heart disease.

SEIZURE: A SYNCOPE MIMIC

Certain features differentiate seizure from syncope:

- In seizure, unconsciousness often lasts longer than 5 minutes

- After a seizure, the patient may experience postictal confusion or paralysis

- Seizure may include prolonged tonic-clonic movements; although these movements may be seen with any form of syncope lasting more than 30 seconds, the movements during syncope are more limited and brief, lasting less than 15 seconds

- Tongue biting strongly suggests seizure.

Urinary incontinence does not help distinguish the two, as it frequently occurs with syncope as well as seizure.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF SYNCOPE

Table 2 lists clinical clues to the type of syncope.2–5,8

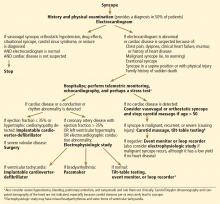

Underlying structural heart disease is the most important predictor of ventricular arrhythmia and death.20,24–26 Thus, the primary goal of the evaluation is to rule out structural heart disease by history, examination, electrocardiography, and echocardiography (Figure 1).

Initial strategy for finding the cause

The cause of syncope is diagnosed by history and physical examination alone in up to 50% of cases, mainly neurally mediated syncope, orthostatic syncope, or seizure.2,3,19

Always check blood pressure with the patient both standing and sitting and in both arms, and obtain an electrocardiogram.

Perform carotid massage in all patients over age 50 if syncope is not clearly vasovagal or orthostatic and if cardiac syncope is not likely. Carotid massage is contraindicated if the patient has a carotid bruit or a history of stroke.

Electrocardiography establishes or suggests a diagnosis in 10% of patients (Table 3, Figure 2).1,2,8,19 A normal electrocardiogram or a mild nonspecific ST-T abnormality suggests a low likelihood of cardiac syncope and is associated with an excellent prognosis. Abnormal electrocardiographic findings are seen in 90% of cases of cardiac syncope and in only 6% of cases of neurally mediated syncope.27 In one study of syncope patients with normal electrocardiograms and negative cardiac histories, none had an abnormal echocardiogram.28

If the heart is normal

If the history suggests neurally mediated syncope or orthostatic hypotension and the history, examination, and electrocardiogram do not suggest coronary artery disease or any other cardiac disease, the workup is stopped.

If the patient has signs or symptoms of heart disease

If the patient has signs or symptoms of heart disease (angina, exertional syncope, dyspnea, clinical signs of heart failure, murmur), a history of heart disease, or exertional, supine, or malignant features, heart disease should be looked for and the following performed:

- Echocardiography to assess left ventricular function, severe valvular disease, and left ventricular hypertrophy

- A stress test (possibly) in cases of exertional syncope or associated angina; however, the overall yield of stress testing in syncope is low (< 5%).29

If electrocardiography and echocardiography do not suggest heart disease

Often, in this situation, the workup can be stopped and syncope can be considered neurally mediated. The likelihood of cardiac syncope is very low in patients with normal findings on electrocardiography and echocardiography, and several studies have shown that patients with syncope who have no structural heart disease have normal long-term survival rates.20,26,30

The following workup may, however, be ordered if the presentation is atypical and syncope is malignant, recurrent, or associated with physical injury, or occurs in the supine position19:

Carotid sinus massage in patients over age 50, if not already performed. Up to 50% of these patients with unexplained syncope have carotid sinus hypersensitivity.13

24-hour Holter monitoring rarely detects significant arrhythmias, but if syncope or dizziness occurs without any arrhythmia, Holter monitoring rules out arrhythmia as the cause of the symptoms.31 The diagnostic yield of Holter monitoring is low (1% to 2%) in patients with infrequent symptoms1,2 and is not improved with 72-hour monitoring.30 The yield is higher in patients with very frequent daily symptoms, many of whom have psychogenic pseudosyncope.2

Tilt-table testing to diagnose vasovagal syncope. This test is positive for a vasovagal response in up to 66% of patients with unexplained syncope.1,19 Patients with heart disease taking vasodilators or beta-blockers may have abnormal baroreflexes. Therefore, a positive tilt test is less specific in these patients and does not necessarily indicate vasovagal syncope.

Event monitoring. If the etiology remains unclear or there are some concerns about arrhythmia, an event monitor (4 weeks of external rhythm monitoring) or an implantable loop recorder (implanted subcutaneously in the prepectoral area for 1 to 2 years) is placed. These monitors record the rhythm when the rate is lower or higher than predefined cutoffs or when the rhythm is irregular, regardless of symptoms. The patient or an observer can also activate the event monitor during or after an event, which freezes the recording of the 2 to 5 minutes preceding the activation and the 1 minute after it.

In a patient who has had syncope, a pacemaker is indicated for episodes of high-grade atrioventricular block, pauses longer than 3 seconds while awake, or bradycardia (< 40 beats per minute) while awake, and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is indicated for sustained ventricular tachycardia, even if syncope does not occur concomitantly with these findings. The finding of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on monitoring increases the suspicion of ventricular tachycardia as the cause of syncope but does not prove it, nor does it necessarily dictate implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator device.

An electrophysiologic study has a low yield in patients with normal electrocardiographic and echocardiographic studies. Bradycardia is detected in 10%.31

If heart disease or a rhythm abnormality is found

If heart disease is diagnosed by echocardiography or if significant electrocardiographic abnormalities are found, perform the following:

Pacemaker placement for the following electrocardiographic abnormalities1,2,19:

- Second-degree Mobitz II or third-degree atrioventricular block

- Sinus pause (> 3 seconds) or bradycardia (< 40 beats per minute) while awake

- Alternating left bundle branch block and right bundle branch block on the same electrocardiogram or separate ones.

Telemetric monitoring (inpatient).

An electrophysiologic study is valuable mainly for patients with structural heart disease, including an ejection fraction 36% to 49%, coronary artery disease, or left ventricular hypertrophy with a normal ejection fraction.32 Overall, in patients with structural heart disease and unexplained syncope, the yield is 55% (inducible ventricular tachycardia in 21%, abnormal indices of bradycardia in 34%).31

However, the yield of electrophysiologic testing is low in bradyarrhythmia and in patients with an ejection fraction of 35% or less.33 In the latter case, the syncope is often arrhythmia-related and the patient often has an indication for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator regardless of electrophysiologic study results, especially if the low ejection fraction has persisted despite medical therapy.32