When patients on target-specific oral anticoagulants need surgery

ABSTRACTThe target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs), eg, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, are changing the way we manage thromboembolic disease. At the same time, many clinicians wonder how best to manage TSOAC therapy when patients need surgery. An in-depth understanding of these drugs is essential to minimize the risk of bleeding and thrombosis perioperatively.

KEY POINTS

- How long before surgery to stop a TSOAC depends on the bleeding risk of the procedure and the patient’s renal function.

- Perioperative bridging is generally unnecessary for patients on TSOACs.

- Routine coagulation assays such as the prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time do not reliably reflect the degree of anticoagulation with TSOACs.

- There are no specific antidotes or standardized reversal strategies for TSOACs.

- TSOACs have a rapid onset of action and should only be restarted postoperatively once hemostasis has been confirmed.

PERIOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF TARGET-SPECIFIC ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

As summarized above, the perioperative management strategy for chronic anticoagulation is based on limited evidence, even for drugs as well established as warfarin.

The most recent ACCP guidelines on the perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy do not mention TSOACs.2 For now, the management strategy must be based on the pharmacokinetics of the drugs, package inserts from the manufacturers, and expert recommendations.3,14,23,32–34 Fortunately, because TSOACs have a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile than that of warfarin, their perioperative uses should be more streamlined. As always, the goal is to minimize the risk of both periprocedural bleeding and thromboembolism.

Timing of cessation of anticoagulation

The timing of cessation of TSOACs before an elective procedure depends primarily on two factors: the bleeding risk of the procedure and the patient’s renal function. Complete clearance of the medication is not necessary in all circumstances.

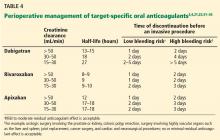

TSOACs should be stopped four to five half-lives before a procedure with a high bleeding risk, so that there is no or only minimal residual anticoagulant effect. The drug can be stopped two to three half-lives before a procedure with a low bleeding risk. Remember: the half-life increases as creatinine clearance decreases.

Specific recommendations may vary across institutions, but a suggested strategy is shown in Table 4.3,4,21,23,32–35 For the small subset of patients on P-glycoprotein or cytochrome P450 inhibitors or inducers, further adjustment in the time of discontinuation may be required.

Therapy does not need to be interrupted for procedures with a very low bleeding risk, as defined above.33,34 There is also preliminary evidence that TSOACs, similar to warfarin, may be continued during cardiac pacemaker or defibrillator placement.36

Evidence from clinical trials of perioperative TSOAC management

While the above recommendations are logical, studies are needed to prospectively evaluate perioperative management strategies.

The RE-LY trial (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy), which compared the effects of dabigatran and warfarin in preventing stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, is one of the few clinical trials that also looked at periprocedural bleeding.37 About a quarter of the RE-LY participants required interruption of anticoagulation for a procedure.

Warfarin was managed according to local practices. For most of the study, the protocol required that dabigatran be discontinued 24 hours before a procedure, regardless of renal function or procedure type. The protocol was later amended and closely mirrored the management plan outlined in Table 4.

With either protocol, there was no statistically significant difference between dabigatran and warfarin in the rates of bleeding and thrombotic complications in the 7 days before or 30 days after the procedure.

A major limitation of the study was that most patients underwent a procedure with a low bleeding risk, so the analysis was likely underpowered to evaluate rates of bleeding in higher-risk procedures.

The ROCKET-AF trial (Rivaroxaban Once-daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation) also shed light on periprocedural bleeding.15 About 15% of the participants required temporary interruption of anticoagulation for a surgical or invasive procedure.38

The study protocol called for discontinuing rivaroxaban 2 days before any procedure. Warfarin was to be held for 4 days to achieve a goal INR of 1.5 or less.15

Rates of major and nonmajor clinically significant bleeding at 30 days were similar with rivaroxaban and with warfarin.38 As with the RE-LY trial, the retrospective analysis was probably underpowered for assessing rates of bleeding in procedures with higher risk.

Perioperative bridging

While stopping a TSOAC in the perioperative period decreases the risk of bleeding, it naturally increases the risk of thromboembolism. However, patients on TSOACs should not routinely require perioperative bridging with an alternative anticoagulant, regardless of thrombotic risk.

Of note, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban carry black-box warnings that discontinuation places patients at higher risk of thrombotic events.3,14,23 These warnings further state that coverage with an alternative anticoagulant should be strongly considered during interruption of therapy for reasons other than pathologic bleeding.

However, it does not necessarily follow that perioperative bridging is required. For example, the warning for rivaroxaban is based on the finding in the ROCKET-AF trial that patients in the rivaroxaban group had higher rates of stroke than those in the warfarin group after the study drugs were stopped at the end of the trial.39 While there was initial concern that this could represent a prothrombotic rebound effect, the authors subsequently showed that patients in the rivaroxaban group were more likely to have had a subtherapeutic INR when transitioning to open-label vitamin-K-antagonist therapy.39,40 There was no difference in the rate of stroke or systemic embolism between the rivaroxaban and warfarin groups when anticoagulation was temporarily interrupted for a procedure.38

The risks and benefits of perioperative bridging with TSOACs are difficult to evaluate, given the dearth of trial data. In the RE-LY trial, only 17% of patients on dabigatran and 28% of patients on warfarin underwent periprocedural bridging.37 The selection criteria and protocol for bridging were not reported. In the ROCKET-AF trial, only 9% of patients received bridging therapy despite a mean CHADS2 score of 3.4.38 (The CHADS2 score is calculated as 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75, and diabetes; 2 points for stroke or transient ischemic attack.) The decision to bridge or not was left to the individual investigator. As a result, the literature offers diverse opinions about the appropriateness of transitioning to an alternative anticoagulant.41–43

Bridging does not make sense in most instances, since anticoagulants such as low-molecular-weight heparin have pharmacokinetics similar to those of the available TSOACs and also depend on renal clearance.41 However, there may be situations in which patients must be switched to a parenteral anticoagulant such as unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin. For example, if a TSOAC has to be held, the patient has acute renal failure, and a needed procedure is still several days away, it would be reasonable to start a heparin drip for an inpatient at increased thrombotic risk.

In patients with normal renal function, these alternative anticoagulants should be started at the time the next TSOAC dose would have been due.3,14,23 In patients with reduced renal function, initiation of an alternative anticoagulant may need to be delayed 12 to 48 hours depending on which TSOAC is being used, as well as on the degree of renal dysfunction. This delay would help ensure that the onset of anticoagulation with the alternative anticoagulant is timed with the offset of therapeutic anticoagulation with the TSOAC.

Although limited, information from available coagulation assays may assist with the timing of initiation of an alternative anticoagulant (see the following section on laboratory monitoring). Serial testing with appropriate coagulation assays may help identify when most of a TSOAC has been cleared from a patient.