STI update: Testing, treatment, and emerging threats

Release date: November 1, 2019

Expiration date: October 31, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity

ABSTRACT

Fast, sensitive molecular diagnostic tests that use urine or self-collected swabs may lead to more screening opportunities and be more acceptable to patients, resulting in faster and more accurate diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and Mycoplasma genitalium infection.

KEY POINTS

- Screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia annually—and more frequently for those at highest risk—in sexually active women age 25 and younger and in men who have sex with men, who should also be screened at the same time for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis.

- Test for Trichomonas vaginalis in women who have symptoms suggesting it, and routinely screen for this pathogen in women who are HIV-positive.

- Nucleic acid amplification is the preferred test for gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and M genitalium infection; the use of urine specimens is acceptable.

- Consider M genitalium if therapy for gonorrhea and chlamydia fails or tests for those diseases are negative.

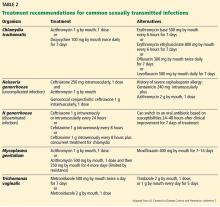

- Single-dose antibiotic therapy is preferred for chlamydia and uncomplicated gonorrhea. It is also available for trichomoniasis, although metronidazole 500 mg twice a day for 7 days has a higher cure rate.

GONORRHEA AND CHLAMYDIA

Gonorrhea and chlamydia are the 2 most frequently reported STIs in the United States, with more than 550,000 cases of gonorrhea and 1.7 million cases of chlamydia reported in 2017.4

Both infections present similarly: cervicitis or urethritis characterized by discharge (mucopurulent discharge with gonorrhea) and dysuria. Untreated, they can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammation, and infertility.

Extragenital infections can be asymptomatic or cause exudative pharyngitis or proctitis. Most people in whom chlamydia is detected from pharyngeal specimens are asymptomatic. When pharyngeal symptoms exist secondary to gonorrheal infection, they typically include sore throat and pharyngeal exudates. However, Komaroff et al,20 in a study of 192 men and women who presented with sore throat, found that only 2 (1%) tested positive for N gonorrhoeae.

,Screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia

Best practices include screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia as follows21–23:

- Every year in sexually active women through age 25 (including during pregnancy) and in older women who have risk factors for infection12

- At least every year in men who have sex with men, at all sites of sexual contact (urethra, pharynx, rectum), along with testing for HIV and syphilis

- Every 3 to 6 months in men who have sex with men who have multiple or anonymous partners, who are sexually active and use illicit drugs, or who have partners who use illicit drugs

- Possibly every year in young men who live in high-prevalence areas or who are seen in certain clinical settings, such as STI and adolescent clinics.

Specimens. A vaginal swab is preferred for screening in women. Several studies have shown that self-collected swabs have clinical sensitivity and specificity comparable to that of provider-collected samples.17,24 First-catch urine or endocervical swabs have similar performance characteristics and are also acceptable. In men, urethral swabs or first-catch urine samples are appropriate for screening for urogenital infections.

Testing methods. Testing for both pathogens should be done simultaneously with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). Commercially available NAATs are more sensitive than culture and antigen testing for detecting gonorrhea and chlamydia.25–27

Most assays are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for testing vaginal, urethral, cervical, and urine specimens. Until recently, no commercial assay was cleared for testing extragenital sites, but recommendations for screening extragenital sites prompted many clinical laboratories to validate throat and rectal swabs for use with NAATs, which are more sensitive than culture at these sites.25,28 The recent FDA approval of extragenital specimen types for 2 commercially available assays may increase the availability of testing for these sites.

Data on the utility of NAATs for detecting chlamydia and gonorrhea in children are limited, and many clinical laboratories have not validated molecular methods for testing in children. Current guidelines specific to this population should be followed regarding test methods and preferred specimen types.12,29,30

Although gonococcal infection is usually diagnosed with culture-independent molecular methods, antimicrobial resistance is emerging. Thus, failure of the combination of ceftriaxone and azithromycin should prompt culture-based follow-up testing to determine antimicrobial susceptibility.

Strategies for treatment and control

Historically, people treated for gonorrhea have been treated for chlamydia at the same time, as these diseases tend to go together. This can be with a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone for the gonorrhea plus a single oral dose of azithromycin for the chlamydia.12 For patients who have only gonorrhea, this double regimen may help prevent the development of resistant gonorrhea strains.

All the patient’s sexual partners in the previous 60 days should be tested and treated, and expedited partner therapy should be offered if possible. Patients should be advised to have no sexual contact until they complete the treatment, or 7 days after single-dose treatment. Testing should be repeated 3 months after treatment.