An overview of endoscopy in neurologic surgery

ABSTRACT

Endoscopy allows neurosurgeons to reach regions in the brain and spine through minimally invasive approaches. Such areas were previously accessible only by extensive and invasive approaches that limited the ability to see the areas of interest. Physicians are increasingly caring for patients who have undergone these procedures (eg, for pituitary tumors, hydrocephalus, and other intracranial, peripheral nerve, and spinal problems). This article familiarizes nonneurosurgeons with these techniques.

KEY POINTS

- An increasing number of neurosurgical patients are undergoing endoscopic surgeries of the brain, spine, and peripheral nerves. Familiarization with these techniques provides medical specialists with important knowledge regarding appropriate patient care.

- The combination of classic microscopic and endoscopic procedures improves surgical outcomes by increasing surgical maneuverability and reducing manipulation of eloquent structures.

- Further innovations in optical physics, electronics, and robotics will dramatically improve the potential of endoscopic neurosurgery in the next decades.

Peripheral nerve surgery

Minimally invasive endoscopic approaches are also being used in peripheral nerve surgery, especially carpal tunnel decompression. The first carpal tunnel release treated endoscopically was performed by Okutsu et al in the late 1980s.8 Since that time, endoscopic carpal tunnel decompression has become very common and is the preferred method for many surgeons, using either single-portal or dual-portal techniques. Although the superiority of endoscopic over conventional minimally invasive microsurgical peripheral nerve surgeries has not been proven, large series of endoscopic carpal tunnel decompressions have reported low complication rates and excellent success rates with high patient satisfaction scores.8,9

Visualization of the spinal canal

Expanding the use of the endoscope to spine surgery, endoscopic explorations of the interlaminar spaces after having completed open surgical laminectomies have been reported since the early 1980s,10 while endoscope-assisted interlaminar procedures started in the late 1990s.11–13 The development of fully endoscopic transforaminal or interlaminar approaches for lumbar stenosis or lumbar disk herniation has been ongoing in the last 2 decades. The rationale for direct endoscopic visualization of the spinal canal is to reduce scarring of the epidural space, which might affect the outcome of possible revision surgeries (recurrent disk herniation), and to reduce injury to the paraspinal muscles, which may reduce postoperative incisional pain and length of hospital stay. Major limiting factors for fully endoscopic spine surgeries such as the narrow working channels (which are limited by the osseous perimeter of the neuroforamina, as well as the pelvis and abdominal structures) and the learning curve for the surgeons are, however, still matters of debate and restrict the use of endoscopy to very carefully selected cases.14,15

Pediatric craniosynostosis

Recently, the use of the endoscope has extended to treatment of craniosynostosis in pediatric patients, historically treated with large and occasionally staged craniotomic approaches. A meta-analysis of the literature showed statistically significant reductions in blood loss and rates of perioperative complications, reoperation, and transfusion compared with open approaches.16

,Technical limitations

While neurosurgeons increasingly advocate the use of the endoscope in their practice, the development of instruments for endoscopic surgery does not always follow the same pace. There are technical problems with current rigid endoscopes and ergonomic limitations of the endoscope-assisted techniques in transcranial neurosurgery. The endoscope itself occupies space in an already limited surgical corridor like the posterior fossa, the parasellar space, or the intraventricular region. The ideal endoscope is thin and sturdy, does not generate heat, and provides high-resolution images. In addition, a self-irrigating feature could minimize the need to remove and reinsert the endoscope for cleaning. Finally, most intracranial surgery is extremely delicate and requires bimanual dissection. The ideal endoscope should also be easily integrated with a holder that allows the surgeon to easily transition between static and dynamic endoscope movements.

Newer flexible fiberscopes with even smaller diameters are likely to be launched on the market in the near future. When working in a surgical corridor less than 10 mm wide, this difference could be substantial.

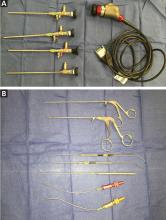

In addition, surgical instruments specifically designed for endoscopic endonasal procedures are needed for microdissection in these regions, which were previously only visible but not reachable endoscopically. These include tools such as malleable suctions and curettes, rotatable back-biting microscissors, and malleable bipolar instruments (Figure 3).

IMPACT OF NEUROENDOSCOPY IN CURRENT CLINICAL PRACTICE

The introduction of endoscopy in neurosurgery changed many treatment paradigms and had an important impact on morbidity and outcomes. In this section, we discuss the specific indications, contraindications, and expected benefit of endoscopic vs open surgical approaches applied to neurosurgical pathology at the present time.

Skull-base tumors and CSF leaks

The use of the endoscope in skull-base surgery was originally applied to purely midline intrasellar tumors without suprasellar or lateral extension beyond the carotid cave. Ideal cases were intrasellar pituitary microadenomas not responding to medical treatment or Rathke cleft cysts.

These pathologies were traditionally addressed via microscopic craniotomic approaches and later through sublabial or transnasal transsphenoidal approaches. Traditional transsphenoidal approaches were highly invasive for the oral mucosa, causing delayed healing, oral dysesthesia, and, in some cases, loss of the superior dental arch (sublabial) or limited visualization and surgical maneuverability (microscopic endonasal).

The endoscope offered better visualization and surgical freedom, thus allowing higher resection rates to be achieved. Resection of purely intrasellar pathology with preservation of the diaphragma sellae as a barrier to the subarachnoid cysterns and third ventricle guaranteed a lower incidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks.

New endoscope optics with varied angles, together with dedicated long surgical instruments with low steric volume, offered a large variety of new endonasal surgical corridors, so-called expanded endonasal approaches on the sagittal and coronal planes, as discussed in detail by Kassam et al.17–19 These allowed endoscopic treatment of invasive tumors extending on the coronary plane into the suprasellar region or invading the cavernous sinuses (pituitary macroadenomas, craniopharyngiomas).

Highly specialized centers with expertise in endoscopic skull-base surgery can now also offer pure endoscopic treatment for some selected cases of lesions located far laterally to the cavernous sinus, such as trigeminal schwannomas, or along the sagittal plane like olfactory groove or tuberculum sellae meningiomas and clival lesions (chordomas, chondrosarcomas).

As one might expect, the increase in surgical complexity corresponded to an increase in complication rates. For example, the incidence of CSF leaks varied from 5% for standard midline transsphenoidal approaches to 11% for expanded endonasal approaches.20,21 The consolidation of the use of the endoscope and the cooperation with ENT surgeons led to the development of surgical strategies to prevent and reduce the incidence of CSF leaks, such as the use of “rescue flaps,” nasoseptal flaps, or temporoparietal fascia flaps.21–23

The development of such techniques allowed endoscopic endonasal approaches to be used in treatment of other pathologies, such as spontaneous CSF leaks, treated in the past with large transcranial repairs that carried high morbidity rates due to the surgical frontal lobe retraction and injury to the olfactory mucosa.24,25 Progress in the field of neuroendoscopy therefore led to the creation of specialized endoscopic skull-base surgery centers, including neurosurgery, ENT, ophthalmology, and endocrinology services.

In clinical practice, when evaluating a patient with intracranial skull-base pathology amenable to endoscopic resection, one should consider referring the patient not only to a neurosurgeon, but also to an ENT surgeon for preoperative assessment of the sinonasal cavities. The same concept applies to postsurgical follow-up, which is mostly performed by the ENT physician to assess nasal mucosa healing and nasal hygiene.