A 66-year-old man with abnormal thyroid function tests

Release date: October 1, 2019

Expiration date: September 30, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

The patient was given oxygen 28% by Venturi mask, and his oxygen saturation went up to 90%. He was started on nebulized albuterol 2.5 mg with ipratropium bromide 500 µg every 4 hours, prednisone 40 mg orally daily for 5 days, and ceftriaxone 1 g intravenously every 24 hours. The first dose of each medication was given in the emergency department.

The patient was then admitted to a progressive care unit, where he was placed on noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, continuous cardiac monitoring, and pulse oximetry. He was started on enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously daily to prevent venous thromboembolism, and the oral medications he had been taking at home were continued. Because he was receiving a glucocorticoid, his blood glucose was monitored in the fasting state, 2 hours after each meal, and as needed.

Two hours after he started noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, his arterial blood gases were remeasured and showed the following results:

,- pH 7.35

- Partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Paco2) 52 mm Hg

- Bicarbonate 28 mmol/L

- Partial pressure of oxygen (Pao2) 60 mm Hg

- Oxygen saturation 90%.

HOSPITAL COURSE

On hospital day 3, his dyspnea had slightly improved. His respiratory rate was 26 to 28 breaths per minute. His oxygen saturation remained between 90% and 92%.

At 10:21 pm, his cardiac monitor showed an episode of focal atrial tachycardia at a rate of 129 beats per minute that lasted for 3 minutes and 21 seconds, terminating spontaneously. He denied any change in his clinical condition during the episode, with no chest pain, palpitation, or change in dyspnea. There was no change in his vital signs. He had another similar asymptomatic episode lasting 4 minutes and 9 seconds at 6:30 am of hospital day 4.

Because of these episodes, the attending physician ordered thyroid function tests.

THYROID FUNCTION TESTING

1. Which thyroid function test is most likely to be helpful in the assessment of this patient’s thyroid status?

- Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) alone

- Serum TSH and total thyroxine (T4)

- Serum TSH and total triiodothyronine (T3)

- Serum TSH and free T4

- Serum TSH and free T3

There are several tests to assess thyroid function: the serum TSH, total T4, free T4, total T3, and free T3 concentrations.1

In normal physiology, TSH from the pituitary stimulates the thyroid gland to produce and secrete T4 and T3, which in turn inhibit TSH secretion through negative feedback. A negative log-linear relation exists between serum free T4 and TSH levels.2 Thus, the serum free T4 level can remain within the normal reference range even if the TSH level is high or low.

TSH assays can have different detection limits. A third-generation TSH assay with a detection limit of 0.01 mU/L is recommended for use in clinical practice.3

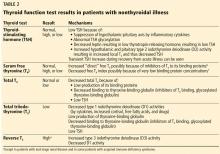

TSH testing alone. Given its superior sensitivity and specificity, serum TSH measurement is considered the best single test for assessing thyroid function in most cases.4 Nevertheless, measurement of the serum TSH level alone could be misleading in several situations, eg, hypothalamic or pituitary disorders, recent treatment of thyrotoxicosis, impaired sensitivity to thyroid hormone, and acute nonthyroidal illness.4

Free vs total T4 and T3 levels

Serum total T4 includes a fraction that is bound, mainly to thyroxin-binding globulin, and a very small unbound (free) fraction. The same applies to T3. Only free thyroid hormones represent the “active” fraction available for interaction with their protein receptors in the nucleus.8 Patients with conditions that can affect the thyroid-binding protein concentrations usually have altered serum total T4 and T3 levels, whereas their free hormone concentrations remain normal. Accordingly, measurement of free hormone levels, especially free T4, is usually recommended.

Although equilibrium dialysis is the method most likely to provide an accurate serum free T4 measurement, it is not commonly used because of its limited availability and high cost. Thus, most commercial laboratories use “direct” free T4 measurement or, to a lesser degree, the free T4 index.9 However, none of the currently available free T4 tests actually measure free T4 directly; rather, they estimate it.10

Commercial laboratories can provide a direct free T3 estimate, but it may be less reliable than total T3. If serum T3 measurement is indicated, serum total T3 is usually measured. However, total T3 measurement is rarely indicated for patients with hypothyroidism because it usually remains within the normal reference range.11 Nevertheless, serum total T3 measurement could be useful in patients with T3 toxicosis and in those who are acutely ill.

Accordingly, in acutely ill hospitalized patients like ours, measuring serum TSH using a third-generation assay and free T4 is essential to assess thyroid function. Many clinicians also measure serum total T3.