Beyond heart health: Consequences of obstructive sleep apnea

Release date: September 1, 2019

Expiration date: August 31, 2022

Estimated time of completion: 0.75 hour

Click here to start this CME activity.

ABSTRACT

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a serious condition associated with impaired quality of life, depression, drowsy driving and motor vehicle accidents, metabolic disease, and cognitive decline. The mechanisms accounting for OSA and metabolic disease include hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, and systemic inflammation. OSA appears to advance cognitive decline, and the relationship between the 2 conditions may be bidirectional. Treatment of patients with continuous positive air pressure therapy improves many of the impaired outcomes associated with OSA. Greater awareness, screening, and treatment of patients with OSA can reduce the negative consequences associated with OSA.

KEY POINTS

- OSA is associated with negative health consequences such as depression, drowsy driving, metabolic disease, and cognitive decline.

- Several possible mechanisms to explain the health consequences of OSA have been explored.

- Treatment of patients with OSA may improve outcomes for many of the health consequences associated with OSA.

- Screening for OSA is important to identify and treat patients to reduce the associated health risks.

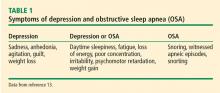

DEPRESSION

Estimates of the prevalence of depression in patients with OSA range from 5% to 63%.13,14 One year after patients were diagnosed with OSA, the incidence of depression per 1,000 person-years was 18% compared with 8% in a group without OSA.14 Women with OSA reportedly have a higher risk of depression (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 2.7) than men (HR 1.81) at 1-year follow-up.14 In the same study, with respect to age, there was no significant relationship noted between OSA and patients over age 64.

A one-level increase in the severity of OSA (ie, from minimal to mild) is associated with a nearly twofold increase in the adjusted odds for depression.15 On the other hand, studies have also found that patients on antidepressants may have an increased risk of OSA.16

,Several potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain the link between depression and OSA.13 Poor-quality sleep, frequent arousal, and fragmentation of sleep in OSA may lead to frontal lobe emotional modulation changes. Intermittent hypoxia in OSA may result in neuronal injury and disruption of noradrenergic and dopaminergic pathways. Pro-inflammatory substances such as interleukin 6 and interleukin 1 are increased in OSA and depression and are mediators between both conditions. Neurotransmitters may be affected by a disrupted sleep-wake cycle. And serotonin, which may be impeded in depression, could influence the upper-airway dilator motor neurons.

Treatment of OSA improves symptoms of depression as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). After 3 months of compliance with CPAP therapy, mean PHQ-9 scores decreased from 11.3 to 2.7 in a study of 228 patients with OSA.17 A study of 1,981 patients with sleep-disordered breathing found improved PHQ-9 scores in patients compliant with CPAP therapy and a greater improvement in patients with a baseline PHQ-9 higher than 10 (moderate severity).18

METABOLIC SYNDROME

OSA is associated with metabolic disorders, including metabolic syndrome, though the causality between these 2 conditions is yet to be illuminated. Metabolic syndrome is a term used when an individual has 3 or more of the following features or conditions:

- Waist circumference greater than 40 inches (men), greater than 35 inches (women)

- Triglycerides 150 mg/dL or greater or treatment for hypertriglyceridemia

- High-density lipoprotein cholesterol less than 40 mg/dL (men), less than 50 mg/dL (women), or treatment for cholesterol

- Blood pressure 130/85 mm Hg or greater, or treatment for hypertension

- Fasting blood glucose 100 mg/dL or greater, or treatment for hyperglycemia.19

Metabolic syndrome increases an individual’s risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease and overall mortality. Like OSA, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome increases with age in both men and women.20,21 The risk of metabolic syndrome is greater with more severe OSA. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort (N = 546) reported an odds ratio for having metabolic syndrome of 2.5 for patients with mild OSA and 2.2 for patients with moderate or severe OSA.22 A meta-analysis also found a 2.4 times higher odds of metabolic syndrome in patients with mild OSA, but a 3.5 times higher odds of metabolic syndrome in patients with moderate to severe OSA compared with the control group.23

Patients with both OSA and metabolic syndrome are said to have syndrome Z24 and are at increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.25 Syndrome Z imparts a higher risk of atherogenic burden and prevalence of atheroma compared with patients with either condition alone.26 In comparing patients with metabolic syndrome with and without OSA, those with OSA had increased atherosclerotic burden as measured by intima-media thickness and carotid femoral pulse-wave velocity.27 Syndrome Z is also linked to intracoronary stenosis related to changes in cardiac morphology28 and is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction.29

OSA and hypertension

Hypertension is one of the conditions encompassed in metabolic syndrome. Several studies report increased risk and incidence of hypertension in patients with OSA. In a community-based study of 6,123 individuals age 40 and older, sleep-disordered breathing was associated with hypertension, and the odds ratio of hypertension was greater in individuals with more severe sleep apnea.30 Similarly, a landmark prospective, population-based study of 709 individuals over 4 years reported a dose-response relationship between patients with OSA and newly diagnosed hypertension independent of confounding factors.31 Patients with moderate to severe OSA had an odds ratio of 2.89 of developing hypertension after adjusting for confounding variables.

A study of 1,889 individuals followed for 12 years found a dose-response relationship based on OSA severity for developing hypertension.32 This study also assessed the incidence of hypertension based on CPAP use. Patients with poor adherence to CPAP use had an 80% increased incidence of hypertension, whereas patients adhering to CPAP use had a 30% decrease in the incidence of hypertension.

Resistant hypertension (ie, uncontrolled hypertension despite use of 3 or more antihypertensive and diuretic medications) has been shown to be highly prevalent (85%) in patients with severe OSA.33 An analysis of patients at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and untreated severe OSA was associated with a 4 times higher risk of elevated blood pressure despite intensive medical therapy.34