Infective endocarditis: Beyond the usual tests

Release date: August 1, 2019

Expiration date: July 31, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

Infective endocarditis remains a diagnostic challenge. Although echocardiography is still the mainstay imaging test, it misses up to 30% of cases. Newer imaging tests—4-dimensional computed tomography (4D CT), fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), and leukocyte scintigraphy—are increasingly used as alternative or adjunct tests for select patients. They improve the sensitivity of clinical diagnosis of infective endocarditis when appropriately used, especially in the setting of a prosthetic valve.

KEY POINTS

- Echocardiography can produce false-negative results in native-valve infective endocarditis and is even less sensitive in patients with a prosthetic valve or cardiac implanted electronic device.

- 4D CT is a reasonable alternative to transesophageal echocardiography. It can also be used as a second test if echocardiography is inconclusive. Coupled with angiography, it also provides a noninvasive method to evaluate coronary arteries perioperatively.

- Nuclear imaging tests—FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy—increase the sensitivity of the Duke criteria for diagnosing infective endocarditis. They should be considered for evaluating suspected infective endocarditis in all patients who have a prosthetic valve or cardiac implanted electronic device, and whenever echocardiography is inconclusive and clinical suspicion remains high.

Limitations of nuclear studies

Both FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy perform poorly for detecting native-valve infective endocarditis. In a study in which 90% of the patients had native-valve infective endocarditis according to the Duke criteria, FDG-PET had a specificity of 93% but a sensitivity of only 39%.20

Both studies can be cumbersome, laborious, and time-consuming for patients. FDG-PET requires a fasting or glucose-restricted diet before testing, and the test itself can be complicated by development of hyperglycemia, although this is rare.

While FDG-PET is most effective in detecting infections of prosthetic valves and cardiac implanted electronic devices, the results can be falsely positive in patients with a history of recent cardiac surgery (due to ongoing tissue healing), as well as maladies other than infective endocarditis that lead to inflammation, such as vasculitis or malignancy. Similarly, for unclear reasons, leukocyte scintigraphy can yield false-negative results in patients with enterococcal or candidal infective endocarditis.21

,FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy are more expensive than TEE and cardiac CT22 and are not widely available.

Both tests entail radiation exposure, with the average dose ranging from 7 to 14 mSv. However, this is less than the average amount acquired during percutaneous coronary intervention (16 mSv), and overlaps with the amount in chest CT with contrast when assessing for pulmonary embolism (7 to 9 mSv). Lower doses are possible with optimized protocols.12,13,15,23

Bottom line for nuclear studies

FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy are especially useful for patients with a prosthetic valve or cardiac implanted electronic device. However, limitations must be kept in mind.

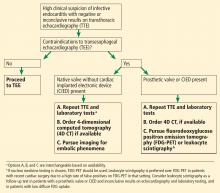

A suggested algorithm for testing with nuclear imaging is shown in Figure 2.1,4

CEREBRAL MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than cerebral CT for detecting emboli in the brain. According to American Heart Association guidelines, cerebral MRI should be done in patients with known or suspected infective endocarditis and neurologic impairment, defined as headaches, meningeal symptoms, or neurologic deficits. It is also often used in neurologically asymptomatic patients with infective endocarditis who have indications for valve surgery to assess for mycotic aneurysms, which are associated with increased intracranial bleeding during surgery.

MRI use in other asymptomatic patients remains controversial.24 In cases with high clinical suspicion for infective endocarditis and no findings on echocardiography, cerebral MRI can increase the sensitivity of the Duke criteria by adding a minor criterion. Some have argued that, in patients with definite infective endocarditis, detecting silent cerebral complications can lead to management changes. However, more studies are needed to determine if there is indeed a group of neurologically asymptomatic infective endocarditis patients for whom cerebral MRI leads to improved outcomes.

Limitations of cerebral MRI

Cerebral MRI cannot be used in patients with non-MRI-compatible implanted hardware.

Gadolinium, the contrast agent typically used, can cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients who have poor renal function. This rare but serious adverse effect is characterized by irreversible systemic fibrosis affecting skin, muscles, and even visceral tissue such as lungs. The American College of Radiology allows for gadolinium use in patients without acute kidney injury and patients with stable chronic kidney disease with a glomerular filtration rate of at least 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Its use should be avoided in patients with renal failure on replacement therapy, with advanced chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), or with acute kidney injury, even if they do not need renal replacement therapy.25

Concerns have also been raised about gadolinium retention in the brain, even in patients with normal renal function.26–28 Thus far, no conclusive clinical adverse effects of retention have been found, although more study is warranted. Nevertheless, the US Food and Drug Administration now requires a black-box warning about this possibility and advises clinicians to counsel patients appropriately.

Bottom line on cerebral MRI

Cerebral MRI should be obtained when a patient presents with definite or possible infective endocarditis with neurologic impairment, such as new headaches, meningismus, or focal neurologic deficits. Routine brain MRI in patients with confirmed infective endocarditis without neurologic symptoms, or those without definite infective endocarditis, is discouraged.

CARDIAC MRI

Cardiac MRI, typically obtained with gadolinium contrast, allows for better 3D assessment of cardiac structures and morphology than echocardiography or CT, and can detect infiltrative cardiac disease, myopericarditis, and much more. It is increasingly used in the field of structural cardiology, but its role for evaluating infective endocarditis remains unclear.

Cardiac MRI does not appear to be better than echocardiography for diagnosing infective endocarditis. However, it may prove helpful in the evaluation of patients known to have infective endocarditis but who cannot be properly evaluated for disease extent because of poor image quality on echocardiography and contraindications to CT.1,29 Its role is limited in patients with cardiac implanted electronic devices, as most devices are incompatible with MRI use, although newer devices obviate this concern. But even for devices that are MRI-compatible, results are diminished due to an eclipsing effect, wherein the device parts can make it hard to see structures clearly because the “brightness” basically eclipses the surrounding area.4

Concerns regarding use of gadolinium as described above need also be considered.

The role of cardiac MRI in diagnosing and managing infective endocarditis may evolve, but at present, the 2017 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association appropriate-use criteria discourage its use for these purposes.16

Bottom line for cardiac MRI

Cardiac MRI to evaluate a patient for suspected infective endocarditis is not recommended due to lack of superiority compared with echocardiography or CT, and the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis from gadolinium in patients with renal compromise.