Gastric outlet obstruction: A red flag, potentially manageable

Release date: May 1, 2019

Expiration date: April 30, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

Gastric outlet obstruction is a common condition in which mechanical obstruction in the distal stomach, pylorus, or duodenum causes nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and early satiety. This article reviews the changing etiology of this disorder and advances in its treatment.

KEY POINTS

- Causes of gastric outlet obstruction fall into 2 categories: benign and malignant. The cause should be presumed to be malignant until proven otherwise.

- Peptic ulcer disease, a benign cause, used to account for most cases of gastric outlet obstruction. It is still common but has declined in frequency with the development of acid-suppressing drugs.

- Gastric cancer used to be the most common malignant cause but has declined in frequency in Western countries with treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Now, pancreatic cancer predominates.

- Endoscopic stenting is an effective, minimally invasive treatment for patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction and poor prognosis, allowing resumption of oral intake and improving quality of life.

MANAGEMENT

Initially, patients with signs and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction should be given:

- Nothing by mouth (NPO)

- Intravenous fluids to correct volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities

- A nasogastric tube for gastric decompression and symptom relief if symptoms persist despite being NPO

- A parenteral proton pump inhibitor, regardless of the cause of obstruction, to decrease gastric secretions41

- Medications for pain and nausea, if needed.

Definitive treatment of gastric outlet obstruction depends on the underlying cause, whether benign or malignant.

Management of benign gastric outlet obstruction

Symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction resolve spontaneously in about half of cases caused by acute peptic ulcer disease, as acute inflammation resolves.9,22

,Endoscopic dilation is an important option in patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction, including peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease-induced gastric outlet obstruction can be safely treated with endoscopic balloon dilation. This treatment almost always relieves symptoms immediately; however, the long-term response has varied from 16% to 100%, and patients may require more than 1 dilation procedure.25,42,43 The need for 2 or more dilation procedures may predict need for surgery.44 Gastric outlet obstruction after caustic ingestion or endoscopic submucosal dissection may also respond to endoscopic balloon dilation.36

Eradication of H pylori may be effective and lead to complete resolution of symptoms in patients with gastric outlet obstruction due to this infection.45–47

NSAIDs should be discontinued in patients with peptic ulcer disease and gastric outlet obstruction. These drugs damage the gastrointestinal mucosa by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes and decreasing synthesis of prostaglandins, which are important for mucosal defense.48 Patients may be unaware of NSAIDs contained in over-the-counter medications and may have difficulty discontinuing NSAIDs taken for pain.49

These drugs are an important cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease and can be detected by platelet COX activity testing, although this test is not widely available. In a study of patients with peptic ulcer disease without definite NSAID use or H pylori infection, up to one-third had evidence of surreptitious NSAID use as detected by platelet COX activity testing.50 In another study,51 platelet COX activity testing discovered over 20% more aspirin users than clinical history alone.

Surgery for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction is used only when medical management and endoscopic dilation fail. Ideally, surgery should relieve the obstruction and target the underlying cause, such as peptic ulcer disease. Laparoscopic surgery is generally preferred to open surgery because patients can resume oral intake sooner, have a shorter hospital stay, and have less intraoperative blood loss.52 The simplest surgical procedure to relieve obstruction is laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.

Patients with gastric outlet obstruction and peptic ulcer disease warrant laparoscopic vagotomy and antrectomy or distal gastrectomy. This removes the obstruction and the stimulus for gastric secretion.53 An alternative is vagotomy with a drainage procedure (pyloroplasty or gastrojejunostomy), which has a similar postoperative course and reduction in gastric acid secretion compared with antrectomy or distal gastrectomy.53,54

Daily proton pump inhibitors can be used for patients with benign gastric outlet obstruction not associated with peptic ulcer disease or risk factors; for such cases, vagotomy is not required.

Management of malignant gastric outlet obstruction

Patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction may have intractable nausea and abdominal pain secondary to retention of gastric contents. The major goal of therapy is to improve symptoms and restore tolerance of an oral diet. The short-term prognosis of malignant gastric outlet obstruction is poor, with a median survival of 3 to 4 months, as these patients often have unresectable disease.55

Surgical bypass used to be the standard of care for palliation of malignant gastric obstruction, but that was before endoscopic stenting was developed.

Endoscopic stenting allows patients to resume oral intake and get out of the hospital sooner with fewer complications than with open surgical bypass. It may be a more appropriate option for palliation of symptoms in patients with malignant obstruction who have a poor prognosis and prefer a less invasive intervention.55,56

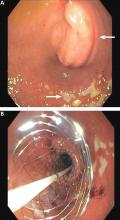

Endoscopic duodenal stenting of malignant gastric outlet obstruction has a success rate of greater than 90%, and most patients can tolerate a mechanical soft diet afterward.34 The procedure is usually performed with a 9-cm or 12-cm self-expanding duodenal stent, 22 mm in diameter, placed over a guide wire under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance (Figure 2). The stent is placed by removing the outer catheter, with distal-to-proximal stent deployment.

Patients who also have biliary obstruction may require biliary stent placement, which is generally performed before duodenal stenting. For patients with an endoscopic stent who develop biliary obstruction, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography can be attempted with placement of a biliary stent; however, these patients may require biliary drain placement by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or by endoscopic ultrasonographically guided transduodenal or transgastric biliary drainage.

From 20% to 30% of patients require repeated endoscopic stent placement, although most patients die within several months after stenting.34 Surgical options for patients who do not respond to endoscopic stenting include open or laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55

Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy may provide better long-term outcomes than duodenal stenting for patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction and a life expectancy longer than a few months.

A 2017 retrospective study of 155 patients with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to unresectable gastric cancer suggested that those who underwent laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy had better oral intake, better tolerance of chemotherapy, and longer overall survival than those who underwent duodenal stenting. Postsurgical complications were more common in the laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy group (16%) than in the duodenal stenting group (0%).57

In most of the studies comparing endoscopic stenting with surgery, the surgery was open gastrojejunostomy; there are limited data directly comparing stenting with laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy.55 Endoscopic stenting is estimated to be significantly less costly than surgery, with a median cost of $12,000 less than gastrojejunostomy.58 As an alternative to enteral stenting and surgical gastrojejunostomy, ultrasonography-guided endoscopic gastrojejunostomy or gastroenterostomy with placement of a lumen-apposing metal stent is emerging as a third treatment option and is under active investigation.59

Patients with malignancy that is potentially curable by resection should undergo surgical evaluation before consideration of endoscopic stenting. For patients who are not candidates for surgery or endoscopic stenting, a percutaneous gastrostomy tube can be considered for gastric decompression and symptom relief.

CASE CONCLUDED

The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic ultrasonography for evaluation of her pancreatic mass. Before the procedure, she was intubated to minimize the risk of aspiration due to persistent nausea and retained gastric contents. A large submucosal mass was found in the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed a mass within the pancreatic head with pancreatic duct obstruction. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed, and pathology study revealed pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent stenting with a 22-mm by 12-cm WallFlex stent (Boston Scientific), which led to resolution of nausea and advancement to a mechanical soft diet on hospital discharge.

She was scheduled for follow-up in the outpatient clinic for treatment of pancreatic cancer.