Evaluating and managing postural tachycardia syndrome

Release date: May 1, 2019

Expiration date: April 30, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a disorder of the autonomic nervous system with many possible causes, characterized by an unexplained increase in heartbeat without change in blood pressure upon standing. Associated cardiac and noncardiac symptoms can severely affect quality of life. Therapy, using a combined approach of diet and lifestyle changes, plus judicious use of medications if needed, can usually improve symptoms and function.

KEY POINTS

- Several POTS subtypes have been recognized, including hypovolemic, neuropathic, and hyperadrenergic forms, overlapping with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, mast cell activation, and autoimmune syndromes.

- Treatment should take a graded approach, beginning with increasing salt and water intake, exercise, and compression stockings.

- If needed, consider medications to expand blood volume, slow heart rate, or reduce central sympathetic tone.

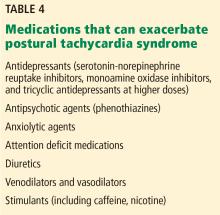

- Certain medications, including venodilators, diuretics, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, can exacerbate symptoms and should be avoided.

GRADED MANAGEMENT

No single universal gold-standard therapy exists for POTS, and management should be individually determined with the primary goals of treating symptoms and restoring function. A graded approach should be used, starting with conservative nonpharmacologic therapies and adding medications as needed.

While the disease course varies substantially from patient to patient, proper management is strongly associated with eventual symptom improvement.1

NONPHARMACOLOGIC STEPS FIRST

Education

Patients should be informed of the nature of their condition and referred to appropriate healthcare personnel. POTS is a chronic illness requiring individualized coping strategies, intensive physician interaction, and support of a multidisciplinary team. Patients and family members can be reassured that most symptoms improve over time with appropriate diagnosis and treatment.1 Patients should be advised to avoid aggravating triggers and activities.

Exercise

Exercise programs are encouraged but should be introduced gradually, as physical activity can exacerbate symptoms, especially at the outset. Several studies have reported benefits from a short-term (3-month) program, in which the patient gradually progresses from non-upright exercise (eg, rowing machine, recumbent cycle, swimming) to upright endurance exercises. At the end of these programs, significant cardiac remodeling, improved quality of life, and reduced heart rate responses to standing have been reported, and benefits have been reported to persist in patients who continued exercising after the 3-month study period.46,47

Despite the benefits of exercise interventions, compliance is low.46,47 To prevent early discouragement, patients should be advised that it can take 4 to 6 weeks of continued exercise before benefits appear. Patients are encouraged to exercise every other day for 30 minutes or more. Regimens should primarily focus on aerobic conditioning, but resistance training, concentrating on thigh muscles, can also help. Exercise is a treatment and not a cure, and benefits can rapidly disappear if regular activity (at least 3 times per week) is stopped.48

Compression stockings

Compression stockings help reduce peripheral venous pooling and enhance venous return to the heart. Waist-high stockings with compression of at least 30 to 40 mm Hg offer the best results.

Diet

Increased fluid and salt intake is advisable for patients with suspected hypovolemia. At least 2 to 3 L of water accompanied by 10 to 12 g of daily sodium intake is recommended.1 This can usually be accomplished with diet and salt added to food, but salt tablets can be used if the patient prefers. The resultant plasma volume expansion may help reduce the reflex tachycardia upon standing.49

Check medications

Rescue therapy with saline infusion

Intravenous saline infusion can augment blood volume in patients who are clinically decompensated and present with severe symptoms.1 Intermittent infusion of 1 L of normal saline has been found to significantly reduce orthostatic tachycardia and related symptoms in patients with POTS, contributing to improved quality of life.51,52

Chronic saline infusions are not recommended for long-term care because of the risk of access complications and infection.1 Moak et al53 reported a high rate of bacteremia in a cohort of children with POTS with regular saline infusions, most of whom had a central line. On the other hand, Ruzieh et al54 reported significantly improved symptoms with regular saline infusions without a high rate of complications, but patients in this study received infusions for only a few months and through a peripheral intravenous catheter.