Three neglected numbers in the CBC: The RDW, MPV, and NRBC count

Release date: March 1, 2019

Expiration date: February 29, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

The complete blood cell count (CBC) is one of the most frequently ordered laboratory tests, but some values included in the test may be overlooked. This brief review discusses 3 potentially underutilized components of the CBC: the red blood cell distribution width (RDW), the mean platelet volume (MPV), and the nucleated red blood cell (NRBC) count. These results have unique diagnostic applications and prognostic implications that can be incorporated into clinical practice. By understanding all components of the CBC, providers can learn more about the patient’s condition.

KEY POINTS

- The RDW can help differentiate the cause of anemia: eg, a high RDW suggests iron-deficiency anemia, while a normal RDW suggests thalassemia. Studies also suggest that a high RDW may be associated with an increased rate of all-cause mortality and may predict a poor prognosis in several cardiac diseases.

- The MPV can be used in the evaluation of thrombocytopenia. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that high MPV is associated with worse outcomes in cardiovascular disorders.

- An elevated NRBC count may predict poor outcomes in a number of critical care settings. It can also indicate a serious underlying hematologic disorder.

MEAN PLATELET VOLUME

The MPV, ie, the average size of platelets, is reported in femtoliters (fL). Because the MPV varies depending on the instrument used, each laboratory has a unique reference range, usually about 8 to 12 fL. The MPV must be interpreted in conjunction with the platelet count; the product of the MPV and platelet count is called the total platelet mass.

Using the MPV to find the cause of thrombocytopenia

The MPV can be used to help narrow the differential diagnosis of thrombocytopenia. For example, it is high in thrombocytopenia resulting from peripheral destruction, as in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. This is because as platelets are lost, thrombopoietin production increases and new, larger platelets are released from healthy megakaryocytes in an attempt to increase the total platelet mass.

In contrast, the MPV is low in patients with thrombocytopenia due to megakaryocyte hypoplasia, as malfunctioning megakaryocytes cannot maintain the total platelet mass, and any platelets produced remain small. This distinction can be obscured in the setting of splenomegaly, as larger platelets are more easily sequestered in the spleen and the MPV may therefore be low or normal.

,The MPV can also be used to differentiate congenital thrombocytopenic disorders, which can be characterized by either a high MPV (eg, gray platelet syndrome, Bernard-Soulier syndrome) or a low MPV (eg, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome) (Figure 2).

MPV may have prognostic value

Evidence suggests that the MPV also has potential prognostic value, particularly in vascular disease, as larger platelets are hypothesized to have increased hemostatic potential.

In a large meta-analysis of patients with coronary artery disease, a high MPV was associated with worse outcomes; the risk of death or myocardial infarction was 17% higher in those with a high MPV (the threshold ranged from 8.4 to 11.7 fL in the different studies) than in those with a low MPV.6

In a study of 213 patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, the risk of significant coronary artery disease was 4.18 times higher in patients with a high MPV and a high troponin level than in patients with a normal MPV and a high troponin.7 The authors suggested that a high MPV may help identify patients at highest risk of significant coronary artery disease who would benefit from invasive studies (ie, coronary angiography).

This correlation has also been observed in other forms of vascular disease. In 261 patients who underwent carotid angioplasty and stenting, an MPV higher than 10.1 fL was associated with a risk of in-stent restenosis more than 3 times higher.8

The MPV has also been found to be higher in patients with type 2 diabetes than in controls, particularly in those with microvascular complications such as retinopathy or microalbuminuria.9

Conversely, in patients with cancer, a low MPV appears to be associated with a poor prognosis. In a retrospective analysis of 236 patients with esophageal cancer, those who had an MPV of 7.4 fL or less had significantly shorter overall survival than patients with an MPV higher than 7.4 fL.10

A low MPV has also been associated with an increased risk of venous thromoboembolism in patients with cancer. In a prospective observational cohort study of 1,544 patients, the 2-year probability of venous thromboembolism was 9% in patients with an MPV less than 10.8 fL, compared with 5.5% in those with higher MPV values. The 2-year overall survival rate was also higher in patients with high MPV than in those with low MPV, at 64.7% vs 55.7%, respectively (P = .001).11

But the MPV is far from a perfect clinical metric. Since its measurement is subject to significant laboratory variation, an abnormal value should always be confirmed with evaluation of a peripheral blood smear. Furthermore, it is unclear why a high MPV portends poor prognosis in patients without cancer, whereas the opposite is true in patients with cancer. Therefore, its role in prognostication remains investigational, and further studies are essential to determine its appropriate usefulness in clinical practice.12

NUCLEATED RED BLOOD CELL COUNT

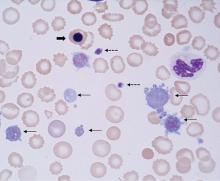

NRBCs are immature red blood cell precursors not present in the circulation of healthy adults. During erythropoiesis, the common myeloid progenitor cell first differentiates into a proerythroblast; subsequently, the chromatin in the nucleus of the proerythroblast gradually condenses until it becomes an orthochromatic erythroblast, also known as a nucleated red cell (Figure 2). Once the nucleus is expelled, the cell is known as a reticulocyte, which ultimately becomes a mature erythrocyte.

Healthy newborns have circulating NRBCs that rapidly disappear within a few weeks of birth. However, NRBCs can return to the circulation in a variety of disease states.

Causes of NRBCs

Brisk hemolysis or rapid blood loss can cause NRBCs to be released into the blood as erythropoiesis increases in an attempt to compensate for acute anemia.

Damage or stress to the bone marrow also causes NRBCs to be released into the peripheral blood, as is often the case in hematologic diseases. In a study of 478 patients with hematologic diseases, the frequency of NRBC positivity at diagnosis was highest in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (100%), acute leukemia (62%), and myelodysplastic syndromes (45%).13 NRBCs also appeared at higher frequencies during chemotherapy in other hematologic conditions, such as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

The mechanism by which NRBCs are expelled from the bone marrow is unclear, though studies have suggested that inflammation or hypoxia or both cause increased hematopoietic stress, resulting in the release of immature red cells. Increased concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (interleukin 6 and interleukin 3) and erythropoietin in the plasma and decreased arterial oxygen partial tension have been reported in patients with circulating NRBCs.14,15

Because they are associated with hematologic disorders, the finding of NRBCs should prompt evaluation of a peripheral smear to assess for abnormalities in other cell lines.

The NRBC count and prognosis

In critically ill patients, peripheral NRBCs can also indicate life-threatening conditions.

In a study of 421 adult intensive care patients, the in-hospital mortality rate was 42% in those with peripheral NRBCs vs 5.9% in those without them.16 Further, the higher the NRBC count and the more days that NRBCs were reported in the CBC, the higher the risk of death.

In adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome, the finding of any NRBCs in the peripheral blood was an independent risk factor for death, and an NRBC count higher than 220 cells/µL was associated with a more than 3-fold higher risk of death.17

Daily screening in patients in surgical intensive care units revealed that NRBCs appeared an average of 9 days before death, consistent with an early marker of impending decline.18

In another study,19 the risk of death within 90 days of hospital discharge was higher in NRBC-positive patients, reaching 21.9% in those who had a count higher than 200 cells/µL. The risk of unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days was also increased.

Leukoerythroblastosis

The combination of NRBCs and immature white blood cells (eg, myelocytes, metamyelocytes) is called leukoerythroblastosis.

Leukoerythroblastosis is classically seen in myelophthisic anemias in which hematopoietic cells in the marrow are displaced by fibrosis, tumor, or other space-occupying processes, but it can also occur in any situation of acute marrow stress, including critical illness.

In addition, leukoerythroblastosis appears in a rare complication of sickle cell hemoglobinopathies: bone marrow necrosis with fat embolism syndrome.20,21 As the marrow necroses, fat emboli are released in the systemic circulation causing micro- and macrovascular occlusions and multiorgan failure. The largest case series in the literature reports 58 patients with bone marrow necrosis with fat embolism syndrome.22

At our institution, we have seen 18 patients with this condition in the past 8 years, with the frequency of diagnosis increasing with heightened awareness of the disorder. We have found that leukoerythroblastosis is often an early marker of this unrecognized syndrome and can prompt emergency red cell exchange, which is considered to be lifesaving in this condition.22

These examples and many others show that the presence of NRBCs in the CBC can serve as an important clinical warning.

OLD TESTS CAN STILL BE USEFUL

The CBC provides much more than simple cell counts; it is a rich collection of information related to each blood cell. These days, with new diagnostic tests and prognostic tools based on molecular analysis, it is important to not overlook the value of the tests clinicians have been ordering for generations.

The RDW, MPV, and NRBC count will not likely provide definitive or flawless diagnostic or prognostic information, but when understood and used correctly, they provide readily available, cost-effective, and useful data that can supplement and guide clinical decision-making. By understanding the CBC more fully, providers can maximize the truly complete nature of this routine laboratory test.