Subclinical hypothyroidism: When to treat

Release date: February 1, 2019

Expiration date: January 31, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

Subclinical hypothyroidism is defined by an elevated serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level along with a normal free thyroxine (T4) level. Whether it should be treated remains controversial. Currently, the best practical approach is to base treatment decisions on the degree of TSH elevation, thyroid autoimmunity, and associated comorbidities.

KEY POINTS

- From 4% to 20% of adults have subclinical hypothyroidism, with a higher prevalence in women, older people, and those with thyroid autoimmunity.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism can progress to overt hypothyroidism, especially if antithyroid antibodies are present, and has been associated with adverse metabolic, cardiovascular, reproductive, maternal-fetal, neuromuscular, and cognitive abnormalities and lower quality of life.

- Some studies have suggested that levothyroxine therapy is beneficial, but others have not, possibly owing to variability in study designs, sample sizes, and patient populations.

- Further trials are needed to clearly demonstrate the clinical impact of subclinical hypothyroidism and the effect of levothyroxine therapy.

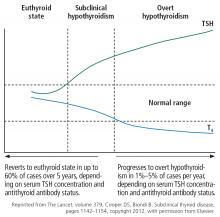

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM CAN RESOLVE OR PROGRESS

“Subclinical” suggests that the disease is in its early stage, with changes in TSH already apparent but decreases in thyroid hormone levels yet to come.17 And indeed, subclinical hypothyroidism can progress to overt hypothyroidism,18 although it has been reported to resolve spontaneously in half of cases within 2 years,19 typically in patients with TSH values of 4 to 6 mIU/L.20 The rate of progression to overt hypothyroidism is estimated to be 33% to 55% over 10 to 20 years of follow-up.18

Figure 1 shows the natural history of subclinical hypothyroidism.1

,GUIDELINES FOR SCREENING DIFFER

Guidelines differ on screening for thyroid disease in the general population, owing to lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials showing treatment benefit in otherwise-healthy people with mildly elevated TSH values.

Various professional societies have adopted different criteria for aggressive case-finding in patients at risk of thyroid disease. Risk factors include family history of thyroid disease, neck irradiation, partial thyroidectomy, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, unexplained weight loss, hyperprolactinemia, autoimmune disorders, and use of medications affecting thyroid function.23

The US Preventive Services Task Force in 2014 found insufficient evidence on the benefits and harms of screening.24

The American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends screening adults starting at age 35, with repeat testing every 5 years in patients who have no signs or symptoms of hypothyroidism, and more frequently in those who do.25

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends screening in women and older patients. Their guidelines and those of the ATA also suggest screening people at high risk of thyroid disease due to risk factors such as history of autoimmune diseases, neck irradiation, or medications affecting thyroid function.26

The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends screening after age 60.18

The American College of Physicians recommends screening patients over age 50 who have symptoms.18

Our approach. Although evidence is lacking to recommend routine screening in adults, aggressive case-finding and treatment in patients at risk of thyroid disease can, we believe, offset the risks associated with subclinical hypothyroidism.24

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

About 70% of patients with subclinical hypothyroidism have no symptoms.13

Tiredness was more common in subclinical hypothyroid patients with TSH levels lower than 10 mIU/L compared with euthyroid controls in 1 study, but other studies have been unable to replicate this finding.27,28

Other frequently reported symptoms include dry skin, cognitive slowing, poor memory, muscle weakness, cold intolerance, constipation, puffy eyes, and hoarseness.13

The evidence in favor of levothyroxine therapy to improve symptoms in subclinical hypothyroidism has varied, with some studies showing an improvement in symptom scores compared with placebo, while others have not shown any benefit.29–31

In one study, the average TSH value for patients whose symptoms did not improve with therapy was 4.6 mIU/L.31 An explanation for the lack of effect in this group may be that the TSH values for these patients were in the high-normal range. Also, because most subclinical hypothyroid patients have no symptoms, it is difficult to ascertain symptomatic improvement. Though it is possible to conclude that levothyroxine therapy has a limited role in this group, it is important to also consider the suggestive evidence that untreated subclinical hypothyroidism may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.