Rapidly progressive pleural effusion

Release date: January 1, 2019

Expiration date: December 31, 2019

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

FURTHER TREATMENT

2. What was the best management strategy for this patient at this time?

- Admit to the hospital for thoracentesis and intravenous antibiotics

- Give oral antibiotics with close follow-up

- Perform thoracentesis on an outpatient basis and give oral antibiotics

- Repeat chest CT

The patient had worsening pleuritic pain with development of a small left pleural effusion. His symptoms had not improved on a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. He now had an elevated white blood cell count with a “left shift” (ie, an increase in neutrophils, indicating more immature cells in circulation) and elevated procalcitonin. The most likely diagnosis was pneumonia with a resulting pleural effusion, ie, parapneumonic effusion, requiring appropriate antibiotic therapy. Ideally, the pleural effusion should be sampled by thoracentesis, with management on an outpatient or inpatient basis.

5 DAYS LATER, THE EFFUSION HAD BECOME MASSIVE

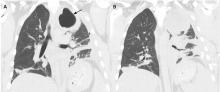

On follow-up 5 days later, the patient’s chest pain was better, but he was significantly more short of breath. His blood pressure was 137/90 mm Hg, heart rate 117 beats/minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation 97% on room air, and temperature 36.9°C (98.4°F). Chest auscultation revealed decreased breath sounds over the left hemithorax, with dullness to percussion and decreased fremitus.

RAPIDLY PROGRESSIVE PLEURAL EFFUSIONS

A rapidly progressive pleural effusion in a healthy patient suggests parapneumonic effusion. The most likely organism is streptococcal.2

Explosive pleuritis is defined as a pleural effusion that increases in size in less than 24 hours. It was first described by Braman and Donat3 in 1986 as an effusion that develops within hours of admission. In 2001, Sharma and Marrie4 refined the definition as rapid development of pleural effusion involving more than 90% of the hemithorax within 24 hours, causing compression of pulmonary tissue and a mediastinal shift. It is a medical emergency that requires prompt investigation and treatment with drainage and antibiotics. All reported cases of explosive pleuritis have been parapneumonic effusion.

The organisms implicated in explosive pleuritis include gram-positive cocci such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, S pyogenes, other streptococci, staphylococci, and gram-negative cocci such as Neisseria meningitidis and Moraxella catarrhalis. Gram-negative bacilli include Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas species, Escherichia coli, Proteus species, Enterobacter species, Bacteroides species, and Legionella species.4,5 However, malignancy is the most common cause of massive pleural effusion, accounting for 54% of cases; 17% of cases are idiopathic, 13% are parapneumonic, and 12% are hydrothorax related to liver cirrhosis.6

CASE CONTINUED

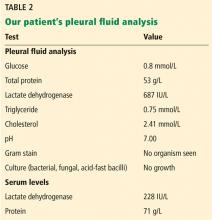

Our patient’s massive effusion needed drainage, and he was admitted to the hospital for further management. Samples of blood and sputum were sent for culture. Intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam was started, and an intercostal chest tube was inserted into the pleural cavity under ultrasonographic guidance to drain turbid fluid.

Multiple pleural fluid samples sent for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli culture were negative. Blood and sputum cultures also showed no growth. The administration of oral antibiotics for 5 days on an outpatient basis before pleural fluid culture could have led to sterility of all cultures.

Our patient had inadequate pleural fluid output through his chest tube, and radiography showed that the pleural collections failed to clear. In fact, an apical locule did not appear to be connecting with the lower aspect of the pleural collection. In such cases, instillation of intrapleural agents through the chest tube has become common practice in an attempt to lyse adhesions, to connect various locules or pockets of pleural fluid, and to improve drainage.