Narcolepsy: Diagnosis and management

ABSTRACT

Narcolepsy is a chronic disorder of hypersomnia that can have a significant impact on quality of life and livelihood. However, with appropriate treatment, its symptoms are manageable, and a satisfying personal, social, and professional life can still be enjoyed. Greater awareness of the disorder promotes accurate and efficient diagnosis. With ongoing research into its underlying biology, better treatments for narcolepsy will inevitably become available.

KEY POINTS

- Features of narcolepsy include daytime sleepiness, sleep attacks, cataplexy (in narcolepsy type 1), sleep paralysis, and sleep-related hallucinations.

- People with narcolepsy feel sleepy and can fall asleep quickly, but they do not stay asleep for long. They go into rapid eye movement sleep soon after falling asleep. Total sleep time is normal, but sleep is fragmented.

- Scheduled naps lasting 15 to 20 minutes can improve alertness. A consistent sleep schedule with good sleep hygiene is also important.

- Modafinil, methylphenidate, and amphetamines are used to manage daytime sleepiness, and sodium oxybate and antidepressants are used for cataplexy.

PSYCHOSOCIAL CONSEQUENCES

Narcolepsy has significant psychosocial consequences. As a result of their symptoms, people with narcolepsy may not be able to meet academic or work-related demands.

Additionally, their risk of a motor vehicle accident is 3 to 4 times higher than in the general population, and more than one-third of patients have been in an accident due to sleepiness.18 There is some evidence to show that treatment eliminates this risk.19

Few systematic studies have examined mood disorders in narcolepsy. However, studies tend to show a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders than in the general population, with depression and anxiety the most com-mon.20,21

DIAGNOSIS IS OFTEN DELAYED

The prevalence of narcolepsy type 1 is between 25 and 100 per 100,000 people.22 In a Mayo Clinic study,23 the incidence of narcolepsy type 1 was estimated to be 0.74 per 100,000 person-years. Epidemiologic data on narcolepsy type 2 are sparse, but patients with narcolepsy without cataplexy are thought to represent only 36% of all narcolepsy patients.23

Diagnosis is often delayed, with the average time between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis ranging from 8 to 22 years. With increasing awareness, the efficiency of the diagnostic process is improving, and this delay is expected to lessen accordingly.24

Symptoms most commonly arise in the second decade; but the age at onset ranges significantly, between the first and fifth decades. Narcolepsy has a bimodal distribution in incidence, with the biggest peak at approximately age 15 and second smaller peak in the mid-30s. Some studies have suggested a slight male predominance.23,25

DIAGNOSIS

History is key

The history should include specific questions about the hallmark features of narcolepsy, including cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and sleep-related hallucinations. For individual assessment of subjective sleepiness, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale or Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale can be administered quickly in the office setting.26,27

The Epworth score is calculated from the self-rated likelihood of falling asleep in 8 different situations, with possible scores of 0 (would never doze) to 3 (high chance of dozing) on each question, for a total possible score of 0 to 24. Normal total scores are between 0 and 10, while scores greater than 10 reflect pathologic sleepiness. Scores on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in those with narcolepsy tend to reflect moderate to severe sleepiness, or at least 13, as opposed to patients with obstructive sleep apnea, whose scores commonly reflect milder sleepiness.28

Testing with actigraphy and polysomnography

It is imperative to rule out insufficient sleep and other sleep disorders as a cause of daytime sleepiness. This can be done with a careful clinical history, actigraphy with sleep logs, and polysomnography.

In the 2 to 4 weeks before actigraphy and subsequent testing, all medications with alerting or sedating properties (including antidepressants) should be tapered off to prevent influence on the results of the study.

Delayed sleep-phase disorder presents at a similar age as narcolepsy and can be associated with similar degrees of sleepiness. However, individuals with delayed sleep phase disorder have an inappropriately timed sleep-wake cycle so that there is a shift in their desired sleep onset and awakening times. It is common—prevalence estimates vary but average about 1% in the general population.29

Insufficient sleep syndrome is even more common, especially in teenagers and young adults, with increasing family, social, and academic demands. Sleep needs vary across the life span. A teenager needs 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night, and a young adult needs 7 to 9 hours. A study of 1,285 high school students found that 10.4% were not getting enough sleep.30

If actigraphy data suggest a circadian rhythm disorder or insufficient sleep that could explain the symptoms of sleepiness, then further testing should be halted and these specific issues should be addressed. In these cases, working with the patient toward maintaining a regular sleep-wake schedule with 7 to 8 hours of nightly sleep will often resolve symptoms.

If actigraphy demonstrates the patient is maintaining a regular sleep schedule and allowing adequate time for nightly sleep, the next step is polysomnography.

Polysomnography is performed to detect other disorders that can disrupt sleep, such as sleep-disordered breathing or periodic limb movement disorder.2,5 In addition, polysomnography can provide assurance that adequate sleep was obtained prior to the next step in testing.

Multiple sleep latency test

If sufficient sleep is obtained on polysomnograpy (at least 6 hours for an adult) and no other sleep disorder is identified, a multiple sleep latency test is performed. A urine toxicology screen is typically performed on the day of the test to ensure that drugs are not affecting the results.

The multiple sleep latency test consists of 4 to 5 nap opportunities at 2-hour intervals in a quiet dark room conducive to sleep, during which both sleep and REM latency are recorded. The sleep latency of those with narcolepsy is significantly shortened, and the diagnosis of narcolepsy requires an average sleep latency of less than 8 minutes.

Given the propensity for REM sleep in narcolepsy, another essential feature for diagnosis is the sleep-onset REM period (SOREMP). A SOREMP is defined as a REM latency of less than 15 minutes. A diagnosis of narcolepsy re-quires a SOREMP in at least 2 of the naps in a multiple sleep latency test (or 1 nap if the shortened REM latency is seen during polysomnography).31

The multiple sleep latency test has an imperfect sensitivity, though, and should be repeated when there is a high suspicion of narcolepsy.32–34 It is not completely specific either, and false-positive results occur. In fact, SOREMPs can be seen in the general population, particularly in those with a circadian rhythm disorder, insufficient sleep, or sleep-disordered breathing. Two or more SOREMPs in an multiple sleep latency test can be seen in a small proportion of the general population.35 The results of a multiple sleep latency test should be interpreted in the clinical context.

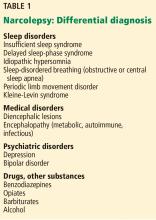

Differential diagnosis

Narcolepsy type 1 is distinguished from type 2 by the presence of cataplexy. A cerebrospinal fluid hypocretin 1 level of 110 pg/mL or less, or less than one-third of the mean value obtained in normal individuals, can substitute for the multiple sleep latency test in diagnosing narcolepsy type 1.31 Currently, hypocretin testing is generally not performed in clinical practice, although it may become a routine part of the narcolepsy evaluation in the future.

Thus, according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition,31 the diagnosis of narcolepsy type 1 requires excessive daytime sleepiness for at least 3 months that cannot be explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, mental disorder, medication use, or substance use disorder, and at least 1 of the following:

- Cataplexy and mean sleep latency of 8 minutes or less with at least 2 SOREMPs on multiple sleep latency testing (1 of which can be on the preceding night’s polysomography)

- Cerebrospinal fluid hypocretin 1 levels less than 110 pg/mL or one-third the baseline normal levels and mean sleep latency ≤ 8 minutes with ≥ 2 SOREMPs on multiple sleep latency testing.

Similarly, the diagnosis of narcolepsy type 2 requires excessive daytime sleepiness for at least 3 months that cannot be explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurological disorder, mental disorder, medication use, or substance use disorder, plus:

- Mean sleep latency of 8 minutes or less with at least 2 SOREMPs on multiple sleep latency testing.

Idiopathic hypersomnia, another disorder of central hypersomnolence, is also characterized by disabling sleepiness. It is diagnostically differentiated from narcolepsy, as there are fewer than 2 SOREMPs. As opposed to narcolepsy, in which naps tend to be refreshing, even prolonged naps in idiopathic hypersomnia are often not helpful in restoring wakefulness. In idiopathic hypersomnia, sleep is usually not fragmented, and there are few nocturnal arousals. Sleep times can often be prolonged as well, whereas in narcolepsy total sleep time through the day may not be increased but is not consolidated.

Kleine-Levin syndrome is a rarer disorder of hypersomnia. It is episodic compared with the relatively persistent sleepiness in narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia. Periods of hypersomnia occur intermittently for days to weeks and are accompanied by cognitive and behavioral changes including hyperphagia and hypersexuality.4

LINKED TO HYPOCRETIN DEFICIENCY

Over the past 2 decades, the underlying pathophysiology of narcolepsy type 1 has been better characterized.

Narcolepsy type 1 has been linked to a deficiency in hypocretin in the central nervous system.36 Hypocretin (also known as orexin) is a hormone produced in the hypothalamus that acts on multiple brain regions and maintains alertness. For unclear reasons, hypothalamic neurons producing hypocretin are selectively reduced in narcolepsy type 1. Hypocretin also stabilizes wakefulness and inhibits REM sleep; therefore, hypocretin deficiency can lead to inappropriate intrusions of REM sleep onto wakefulness, leading to the hallmark features of narcolepsy—cataplexy, sleep-related hallucinations, and sleep paralysis.37 According to one theory, cataplexy is triggered by emotional stimuli because of a pathway between the medial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala to the pons.38

Cerebrospinal fluid levels of hypocretin in patients with narcolepsy type 2 tend to be normal, and the biologic underpinnings of narcolepsy type 2 remain mysterious. However, in the subgroup of those with narcolepsy type 2 in which hypocretin is low, many individuals go on to develop cataplexy, thereby evolving to narcolepsy type 1.36

POSSIBLE AUTOIMMUNE BASIS

Narcolepsy is typically a sporadic disorder, although familial cases have been described. The risk of a parent with narcolepsy having a child who is affected is approximately 1%.5

Narcolepsy type 1 is strongly associated with HLA-DQB1*0602, with up to 95% of those affected having at least one allele.39 Having 2 copies of the allele further increases the risk of developing narcolepsy.40 However, this allele is far from specific for narcolepsy with cataplexy, as it occurs in 12% to 38% of the general population.41 Therefore, HLA typing currently has limited clinical utility. The exact cause is as yet unknown, but substantial literature proposes an autoimmune basis of the disorder, given the strong association with the HLA subtype.42–44

After the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, there was a significant increase in the incidence of narcolepsy with cataplexy, which again sparked interest in an autoimmune etiology underlying the disorder. Pandemrix, an H1N1 vaccine produced as a result of the 2009 pandemic, appeared to also be associated with an increase in the incidence of narcolepsy. An association with other upper respiratory infections has also been noted, further supporting a possible autoimmune basis.

A few studies have looked for serum autoantibodies involved in the pathogenesis of narcolepsy. Thus far, only one has been identified, an antibody to Tribbles homolog 2, found in 20% to 40% of those with new onset of nar-colepsy.42–44

TREATMENTS FOR DAYTIME SLEEPINESS

As with many chronic disorders, the treatment of narcolepsy consists of symptomatic rather than curative management, which can be done through both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic means.

Nondrug measures

Scheduled naps lasting 15 to 20 minutes can help improve alertness.45 A consistent sleep schedule with good sleep hygiene, ensuring sufficient nightly sleep, is also important. In one study, the combination of scheduled naps and regular nocturnal sleep times reduced the level of daytime sleepiness and unintentional daytime sleep. Daytime naps were most helpful for those with the highest degree of daytime sleepiness.45

Strategic use of caffeine can be helpful and can reduce dependence on pharmacologic treatment.

Screening should be performed routinely for other sleep disorders, such as sleep-disordered breathing, which should be treated if identified.5,18 When being treated for other medical conditions, individuals with narcolepsy should avoid medications that can cause sedation, such as opiates or barbiturates; alcohol should be minimized or avoided.

Networking with other individuals with narcolepsy through support groups such as Narcolepsy Network can be valuable for learning coping skills and connecting with community resources. Psychological counseling for the patient, and sometimes the family, can also be useful. School-age children may need special accommodations such as schedule adjustments to allow for scheduled naps or frequent breaks to maintain alertness.

People with narcolepsy tend to function better in careers that do not require long periods of sitting, as sleepiness tends to be worse, but instead offer flexibility and require higher levels of activity that tend to combat sleepiness. They should not work as commercial drivers.18