Perioperative cardiovascular medicine: 5 questions for 2018

ABSTRACT

A MEDLINE search was performed from January 2017 to February 2018, and articles were selected for this update based on their significant influence on the practice of perioperative cardiovascular medicine.

KEY POINTS

- Patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who have a history of percutaneous coronary intervention will benefit from continuing aspirin perioperatively if they are not at very high risk of bleeding.

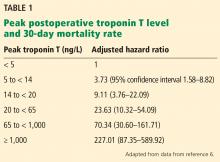

- Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery is strongly associated with a risk of death, and the higher the troponin level, the higher the risk. Measuring troponin T before and after surgery may be beneficial in patients at high risk if the information leads to a change in management.

- Perioperative hypotension can lead to end-organ dysfunction postoperatively. There is conflicting evidence whether the absolute or relative reduction in blood pressure is more predictive.

- Perioperative risk of stroke is higher in patients with patent foramen ovale than in those without.

- Many patients who recently had a stroke suffer recurrent stroke and major adverse cardiac events if they undergo emergency surgery.

WHAT IS THE INCIDENCE OF MINS? IS MEASURING TROPONIN USEFUL?

Despite advances in anesthesia and surgical techniques, about 1% of patients over age 45 die within 30 days of noncardiac surgery.4 Studies have demonstrated a high mortality rate in patients who experience myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery (MINS), defined as elevations of troponin T with or without ischemic symptoms or electrocardiographic changes.5 Most of these studies used earlier, “non-high-sensitivity” troponin T assays. Fifth-generation, highly sensitive troponin T assays are now available that can detect troponin T at lower concentrations, but their utility in predicting postoperative outcomes remains uncertain. Two recent studies provide further insight into these issues.

[Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators, Devereaux PJ, Biccard BM, Sigamani A, et al. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2017; 317(16):1642–1651.]

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study5 was an international, prospective cohort study that initially evaluated the association between MINS and the 30-day mortality rate using a non-high-sensitivity troponin T assay (Roche fourth-generation Elecsys TnT assay) in patients age 45 or older undergoing noncardiac surgery and requiring hospital admission for at least 1 night. After the first 15,000 patients, the study switched to the Roche fifth-generation assay, with measurements at 6 to 12 hours after surgery and on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3.

,A 2017 analysis by Devereaux et al6 included only these later-enrolled patients and correlated their high-sensitivity troponin T levels with 30-day mortality rates. Patients with a level 14 ng/L or higher, the upper limit of normal in this study, were also assessed for ischemic symptoms and electrocardiographic changes. Although not required by the study, more than 7,800 patients had their troponin T levels measured before surgery, and the absolute change was also analyzed for an association with the 30-day mortality rate.

Findings. Of the 21,842 patients, about two-thirds underwent some form of major surgery; some of them had more than 1 type. A total of 1.2% of the patients died within 30 days of surgery.

Based on their analysis, the authors proposed that MINS be defined as:

- A postoperative troponin T level of 65 ng/L or higher, or

- A level in the range of 20 ng/L to less than 65 ng/L with an absolute increase from the preoperative level at least 5 ng/L, not attributable to a nonischemic cause.

Seventeen percent of the study patients met these criteria, and of these, 21.7% met the universal definition of myocardial infarction, although only 6.9% had symptoms of it.

Limitations. Only 40.4% of the patients had a preoperative high-sensitivity troponin T measurement for comparison, and in 13.8% of patients who had an elevated perioperative measurement, their preoperative value was the same or higher than their postoperative one. Thus, the incidence of MINS may have been overestimated if patients were otherwise not known to have troponin T elevations before surgery.

[Puelacher C, Lurati Buse G, Seeberger D, et al. Perioperative myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: incidence, mortality, and characterization. Circulation 2018; 137(12):1221–1232.]

Puelacher et al7 investigated the prevalence of MINS in 2,018 patients at increased cardiovascular risk (age ≥ 65, or age ≥ 45 with a history of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, or stroke) who underwent major noncardiac surgery (planned overnight stay ≥ 24 hours) at a university hospital in Switzerland. Patients had their troponin T measured with a high-sensitivity assay within 30 days before surgery and on postoperative days 1 and 2.

Instead of MINS, the investigators used the term “perioperative myocardial injury” (PMI), defined as an absolute increase in troponin T of at least 14 ng/L from before surgery to the peak postoperative reading. Similar to MINS, PMI did not require ischemic features, but in this study, noncardiac triggers (sepsis, stroke, or pulmonary embolus) were not excluded.

Findings. PMI occurred in 16% of surgeries, and of the patients with PMI, 6% had typical chest pain and 18% had any ischemic symptoms. Unlike in the POISE-2 study discussed above, PMI triggered an automatic referral to a cardiologist.

The unadjusted 30-day mortality rate was 8.9% among patients with PMI and 1.5% in those without. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed an adjusted hazard ratio for 30-day mortality of 2.7 (95% CI 1.5–4.8) for those with PMI vs without, and this difference persisted for at least 1 year.

In patients with PMI, the authors compared the 30-day mortality rate of those with no ischemic signs or symptoms (71% of the patients) with those who met the criteria for myocardial infarction and found no difference. Patients with PMI triggered by a noncardiac event had a worse prognosis than those with a presumed cardiac etiology.

Limitations. Despite the multivariate analysis that included adjustment for age, nonelective surgery, and Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI), the increased risk associated with PMI could simply reflect higher risk at baseline. Although PMI resulted in automatic referral to a cardiologist, only 10% of patients eventually underwent coronary angiography; a similar percentage were discharged with additional medical therapy such as aspirin, a statin, or a beta-blocker. The effect of these interventions is not known.

Conclusions. MINS is common and has a strong association with mortality risk proportional to the degree of troponin T elevation using high-sensitivity assays, consistent with data from previous studies of earlier assays. Because the mechanism of MINS may differ from that of myocardial infarction, its prevention and treatment may differ, and it remains unclear how serial measurement in postoperative patients should change clinical practice.

The recently published Dabigatran in Patients With Myocardial Injury After Non-cardiac Surgery (MANAGE) trial8 suggests that dabigatran may reduce arterial and venous complications in patients with MINS, but the study had a number of limitations that may restrict the clinical applicability of this finding.

While awaiting further clinical outcomes data, pre- and postoperative troponin T measurement may be beneficial in higher-risk patients (such as those with cardiovascular disease or multiple RCRI risk factors) if the information will change perioperative management.