Pulmonary infarction due to pulmonary embolism

HOW DOES PULMONARY INFARCTION PRESENT CLINICALLY?

3. Which of the following statements about pulmonary infarction is incorrect?

- Cavitation and infarction are more common with larger emboli

- Cavitation occurs in fewer than 10% of pulmonary infarctions

- Lung abscess develops in more than 50% of pulmonary infarctions

- Pulmonary thromboembolism is the most common cause of pulmonary infarction

Lung abscess develops in far fewer than 50% of cases of pulmonary infarction. The rest of the statements are correct.

Cavitation complicates about 4% to 7% of infarctions and is more common when the infarction is 4 cm or greater in diameter.4 These cavities are usually single and predominantly on the right side in the apical or posterior segment of the upper lobe or the apical segment of the right lower lobe, as in our patient.5–8 CT demonstrating scalloped inner margins and cross-cavity band shadows suggests a cavitary pulmonary infarction.9,10

Infection and abscess in pulmonary infarction are poorly understood but have been linked to larger infarctions, coexistent congestion or atelectasis, and dental or oropharyngeal infection. In an early series of 550 cases of pulmonary infarction, 23 patients (4.2%) developed lung abscess and 6 (1.1%) developed empyema.11 The mean time to cavitation for an infected pulmonary infarction has been reported to be 18 days.12

A reversed halo sign, generally described as a focal, rounded area of ground-glass opacity surrounded by a nearly complete ring of consolidation, has been reported to be more frequent with pulmonary infarction than with other diseases, especially when in the lower lobes.13

CASE CONTINUED: THORACOSCOPY

A cardiothoracic surgeon was consulted, intravenous heparin was discontinued, an inferior vena cava filter was placed, and the patient underwent video-assisted thoracoscopy.

Purulent fluid was noted on the lateral aspect of right lower lobe; this appeared to be the ruptured cavitary lesion functioning like an uncontrolled bronchopleural fistula. Two chest tubes, sizes 32F and 28F, were placed after decortication, resection of the lung abscess, and closure of the bronchopleural fistula. No significant air leak was noted after resection of this segment of lung.

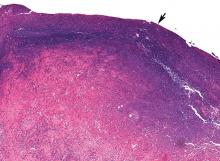

Pathologic study showed acute organizing pneumonia with abscess formation; no malignant cells or granulomas were seen (Figure 2). Pleural fluid cultures grew Streptococcus intermedius, while the tissue culture was negative for any growth, including acid-fast bacilli and fungi.

On 3 different occasions, both chest tubes were shortened, backed out 2 cm, and resecured with sutures and pins, and Heimlich valves were applied before the patient was discharged.

Intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam was started on the fifth hospital day. On discharge, the patient was advised to continue this treatment for 3 weeks at home.

The patient was receiving enoxaparin subcutaneously in prophylactic doses; 72 hours after the thorascopic procedure this was increased to therapeutic doses, continuing after discharge. Bridging to warfarin was not advised in view of his chest tubes.

Our patient appeared to have developed a right lower lobe infarction that cavitated and ruptured into the pleural space, causing a bronchopleural fistula with empyema after a recent pulmonary embolism. Other reported causes of pulmonary infarction in pulmonary embolism are malignancy and heavy clot burden,6 but these have not been confirmed in subsequent studies.5 Malignancy was ruled out by biopsy of the resected portion of the lung, and our patient did not have a history of heart failure. A clear cavity was not noted (because it ruptured into the pleura), but an air-fluid level was described in a wedge-shaped consolidation, suggesting infarction.

How common is pulmonary infarction after pulmonary embolism?

Pulmonary infarction occurs in few patients with pulmonary embolism.13 Since the lungs receive oxygen from the airways and have a dual blood supply from the pulmonary and bronchial arteries, they are not particularly vulnerable to ischemia. However, the reported incidence of pulmonary infarction in patients with pulmonary embolism has ranged from 10% to higher than 30%.5,14,15

The reasons behind pulmonary infarction with complications after pulmonary embolism have varied in different case series in different eras. CT, biopsy, or autopsy studies reveal pulmonary infarction after pulmonary embolism to be more common than suspected by clinical symptoms.

In a Mayo Clinic series of 43 cases of pulmonary infarction diagnosed over a 6-year period by surgical lung biopsy, 18 (42%) of the patients had underlying pulmonary thromboembolism, which was the most common cause.16