Phosphorus binders: The new and the old, and how to choose

ABSTRACT

In caring for patients with chronic kidney disease, it is important to prevent and treat hyperphosphatemia with a combination of dietary restrictions and phosphorus binders. This review describes the pathophysiology and control of hyperphosphatemia and the different classes of phosphorus binders with respect to their availability, cost, side effects, and scenarios in which one class of binder may be more beneficial than another.

KEY POINTS

- Serum phosphorus is maintained within normal levels in a tightly regulated system involving interplay between organs, hormones, diet, and other factors.

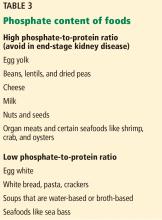

- Dietary phosphorus comes mainly from protein, so restricting phosphorus without introducing protein deficiency is difficult. Food with a low phosphorus-to-protein ratio and plant-based sources of protein may be preferable.

- Although dialysis removes phosphorus, it usually does not remove enough, and many patients require phosphorus-binding drugs.

- Selection of an appropriate binder should consider serum calcium levels, pill burden, serum iron stores, and cost.

HYPERPHOSPHATEMIA MAY LEAD TO VASCULAR CALCIFICATION

Elevated serum phosphorus levels (normal range 2.48–4.65 mg/dL in adults11) are associated with cardiovascular calcification and subsequent increases in mortality and morbidity rates. Elevations in serum phosphorus and calcium levels are associated with progression in vascular calcification12 and likely account for the accelerated vascular calcification that is seen in kidney disease.13

Hyperphosphatemia has been identified as an independent risk factor for death in patients with end-stage renal disease,14 but that relationship is less clear in patients with chronic kidney disease. A study in patients with chronic kidney disease and not on dialysis found a lower mortality rate in those who were prescribed phosphorus binders,15 but the study was criticized for limitations in its design.

Hyperphosphatemia can also lead to adverse effects on bone health due to complications such as renal osteodystrophy.

However, in its 2017 update, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) program only “suggests” lowering elevated phosphorus levels “toward” the normal range in patients with chronic kidney disease stages G3a through G5D, ie, those with glomerular filtration rates less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, including those on dialysis. The recommendation is graded 2C, ie, weak, based on low-quality evidence (https://kdigo.org/guidelines/ckd-mbd).

DIETARY RESTRICTION OF PHOSPHORUS

Diet is the major source of phosphorus intake. The average daily phosphorus consumption is 20 mg/kg, or 1,400 mg, and protein is the major source of dietary phosphorus.

In patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease, the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative recommends limiting protein intake to 0.6 mg/kg/day.16 However, in patients on hemodialysis, they recommend increasing protein intake to 1.1 mg/kg/day while limiting phosphorus intake to about 800 to 1,000 mg/day. This poses a challenge, as limiting phosphorus intake can reduce protein intake.

Sources of protein can be broadly classified as plant-based or animal-based. Animal protein contains organic phosphorus, which is easily absorbed.18 Plant protein may not be absorbed as easily.

Moe et al19 studied the importance of the protein source of phosphorus after 7 days of controlled diets. Despite equivalent protein and phosphorus concentrations in the vegetarian and meat-based diets, participants on the vegetarian diet had lower serum phosphorus levels, a trend toward lower 24-hour urinary phosphorus excretion, and significantly lower FGF23 levels than those on the meat-based diet. This suggests that a vegetarian diet may have advantages in terms of preventing hyperphosphatemia.

Another measure to reduce phosphorus absorption from meat is to boil it, which reduces the phosphorus content by 50%.20

Processed foods containing additives and preservatives are very high in phosphorus21 and should be avoided, particularly as there is no mandate to label phosphorus content in food.

PHOSPHORUS AND DIALYSIS

Although hemodialysis removes phosphorus, it does not remove enough to keep levels within normal limits. Indeed, even when patients adhere to a daily phosphorus limit of 1,000 mg, phosphorus accumulates. If 70% of the phosphorus in the diet is absorbed, this is 4,500 to 5,000 mg in a week. A 4-hour hemodialysis session will remove only 1,000 mg of phosphorus, which equals about 3,000 mg for patients undergoing dialysis 3 times a week,22 far less than phosphorus absorption.

In patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, a daily regimen of 4 exchanges of 2 L per exchange removes about 200 mg of phosphorus per day. In a 2012 study, patients on nocturnal dialysis or home dialysis involving longer session length had greater lowering of phosphorus levels than patients undergoing routine hemodialysis.23

Hence, phosphorus binders are often necessary in patients on routine hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

PHOSPHORUS BINDERS

Phosphorus binders reduce serum phosphorus levels by binding with ingested phosphorus in the gastrointestinal tract and forming insoluble complexes that are not absorbed. For this reason they are much more effective when taken with meals. Phosphorus binders come in different formulations: pills, capsules, chewable tablets, liquids, and even powders that can be sprinkled on food.

The potency of each binder is quantified by its “phosphorus binder equivalent dose,” ie, its binding capacity compared with that of calcium carbonate as a reference.24

Phosphorus binders are broadly divided into those that contain calcium and those that do not.

Calcium-containing binders

The 2 most commonly used preparations are calcium carbonate (eg, Tums) and calcium acetate (eg, Phoslo). While these are relatively safe, some studies suggest that their use can lead to accelerated vascular calcification.25

According to KDIGO,26 calcium-containing binders should be avoided in hypercalcemia and adynamic bone disease. Additionally, the daily elemental calcium intake from binders should be limited to 1,500 mg, with a total daily intake that does not exceed 2,000 mg.

The elemental calcium content of calcium carbonate is about 40% of its weight (eg, 200 mg of elemental calcium in a 500-mg tablet of Tums), while the elemental calcium content of calcium acetate is about 25%. Therefore, a patient who needs 6 g of calcium carbonate for efficacy will be ingesting 2.4 g of elemental calcium per day, and that exceeds the recommended daily maximum. The main advantage of calcium carbonate is its low cost and easy availability. Commonly reported side effects include nausea and constipation.

A less commonly used calcium-based binder is calcium citrate (eg, Calcitrate). It should, however, be avoided in chronic kidney disease because of the risk of aluminum accumulation. Calcium citrate can enhance intestinal absorption of aluminum from dietary sources, as aluminum can form complexes with citrate.27