Phosphorus in kidney disease: Culprit or bystander?

STRATEGIES TO CONTROL HYPERPHOSPHATEMIA

Reducing intake

Dietary phosphorus restriction is the first step in controlling serum phosphorus. But reducing phosphorus intake while otherwise trying to optimize the nutritional status can be challenging.

The recommended daily protein intake is 1.0 to 1.2 g/kg. But phosphorus is typically found in foods rich in proteins, and restricting protein severely can compromise nutritional status and may be as bad as elevated phosphate levels in terms of outcomes.

Although plant-based foods contain more phosphate per gram of protein (ie, they have a higher ratio of phosphorus to protein) than animal-based foods, the bioavailability of phosphorus from plant foods is lower. Phosphorus in plant-based foods is mainly in the form of phytate. Humans cannot hydrolyze phytate because we lack the phytase enzyme; hence, the phosphorus in plant-based foods is not well absorbed. Therefore, a vegetarian diet may be preferable and beneficial in patients with chronic kidney disease. A small study in humans showed that a vegetarian diet resulted in lower serum phosphorus and FGF23 levels, but the study was limited by its small sample size.12

Patients should be advised to avoid foods that have a high phosphate content, such as processed foods, fast foods, and cola beverages, which often have phosphate-based food additives.

Further, one should be cautious about using supplements with healthy-sounding names. A case in point is “vitamin water”: 12 oz of this fruit punch-flavored beverage contains 392 mg of phosphorus,13 and this alone would require 12 to 15 phosphate binder tablets to bind its phosphorus content.

In addition, many prescription drugs have significant amounts of phosphorus, and this is often unrecognized.

Sherman et al14 reviewed 200 of the most commonly prescribed drugs in dialysis patients and found that 23 (11.5%) of the drug labels listed phosphorus-containing ingredients, but the actual amount of phosphorus was not listed. The phosphorus content ranged from 1.4 mg (clonidine 0.2 mg, Blue Point Laboratories, Dublin, Ireland) to 111.5 mg (paroxetine 40 mg, GlaxoSmith Kline, Philadelphia, PA). The phosphorus content was inconsistent and varied with the dose of the agent, type of formulation (tablet or syrup), branded or generic formulation, and manufacturer.

Branded lisinopril (Merck, Kenilworth, NJ) had 21.4 mg of phosphorus per 10-mg dose, while a generic product (Blue Point Laboratories, Dublin, Ireland) had 32.6 mg. Different brands of generic amlodipine 10 mg varied in their phosphorus content from 8.6 mg (Lupin Pharmaceuticals, Mumbai, India) to 27.8 mg (Greenstone LLC, Peapack, NJ) to 40.1 mg (Qualitest Pharmaceuticals, Huntsville, AL. Rena-Vite (Cypress Pharmaceuticals, Madison, MS), a multivitamin marketed to patients with kidney disease, had 37.7 mg of phosphorus per tablet. Thus, just to bind the phosphorus content of these 3 tablets (lisinopril, amlodipine, and Rena-Vite), a patient could need at least 3 to 4 extra doses of phosphate binder.

The phosphate content of medications should be considered when prescribing. For example, Reno Caps (Nnodum Pharmaceuticals, Cincinnati, OH), another vitamin supplement, has only 1.7 mg of phosphorus per tablet and should be considered, especially in patients with poorly controlled serum phosphorus levels. However, the challenge is that medication labels do not provide the phosphorus content.

Reducing phosphorus absorption

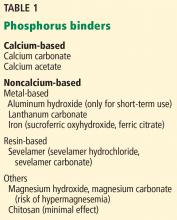

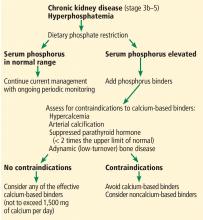

Although these agents reduce serum phosphorus and help reduce symptoms, an important quality-of-life measure, it is uncertain whether they improve clinical outcomes.11 To date, no specific phosphorus binder offers a survival benefit over placebo.11

Based on the limited and conflicting evidence, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, recently updated, suggest that oral phosphorus binders should be used in patients with hyperphosphatemia to lower serum phosphorus levels toward the normal range.15 They further recommend not exceeding 1,500 mg of elemental calcium per day if a calcium-based binder is used, and they recommend avoiding calcium-based binders in patients with hypercalcemia, adynamic bone disease, or vascular calcification.

Phosphorus binders may account for up to 50% of the daily pill burden and may contribute to poor medication adherence.16 Dialysis patients need to take a lot of these drugs: by weight, 5 to 6 pounds per year.

These drugs can bind and interfere with the absorption of other vital medications and so should be taken with meals and separately from other medications.

Removing phosphorus

Removal of phosphorus by adequate dialysis or kidney transplant is the final strategy.

New agents under study

To improve phosphorus control, other agents that inhibit absorption of phosphate are being investigated.

Nicotinamide reduces expression of the sodium-phosphorus cotransporter NTP2b. Its use in combination with a low-phosphorus diet and phosphorus binders may maximize reductions in phosphorus absorption and is being studied in the CKD Optimal Management With Binders and Nicotinamide (COMBINE) study.

Tenapanor, an inhibitor of the sodium-hydrogen transporter NHE3, has been shown in animal studies to increase fecal phosphate excretion and decrease urinary phosphate excretion17 but requires further evaluation.