Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: What primary care physicians need to know

ABSTRACT

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a specific type of fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause. It is usually chronic and progressive, tends to affect mainly adults over age 60, has a predilection for men, and is often fatal. The condition is still underappreciated by pulmonologists and primary care physicians. This article attempts to close that information gap by reviewing the natural course of IPF and presenting an algorithmic approach to diagnosis and treatment based on evidence-based international guidelines. New treatment options are briefly discussed, to raise awareness of new medications that target pulmonary fibrosis.

KEY POINTS

- IPF is characterized by a pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia on imaging and histopathology without another known etiology.

- We recommend early referral to a center specializing in interstitial lung disease to confirm the diagnosis and to initiate appropriate therapy.

- Specialized centers offer advice on prognosis, enrollment in disease registries and clinical trials, and candidacy for lung transplant.

SYMPTOMS AND KEY FEATURES

Patients with IPF typically present with the insidious onset of dyspnea on exertion, with or without chronic cough. Risk factors include male sex, increasing age, and a history of smoking. Patients with undiagnosed IPF who present with dyspnea and a history of smoking are often treated empirically for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Rales are a common finding on auscultation in IPF, and this can lead to an exhaustive cardiac evaluation and empiric treatment for heart failure. Digital clubbing is also relatively common.14 Hypoxemia with exertion is another common feature that also often correlates with disease severity and prognosis. Resting hypoxemia is more common in advanced disease.

On spirometry, patients with IPF typically demonstrate restrictive physiology, suggested by a normal or elevated ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 second to the forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) (> 70% predicted or above the lower limit of normal) combined with a lower than normal FVC. Restrictive physiology is definitively demonstrated by a decreased total lung capacity (< 80% predicted or below the lower limit of normal) on plethysmography. Impaired gas exchange, manifested by a decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) on pulmonary function testing, is also common. Because pulmonary perfusion is higher in the lung bases, where IPF is also predominant, the DLCO is often reduced to a greater extent than the FVC.

PROGNOSTIC INDICATORS

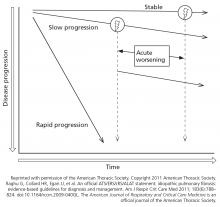

Clinicians typically view IPF as a relentless and progressive process, but its course is variable and can be uncertain in an individual patient (Figure 1).15,16 Nevertheless, over time, most patients have a decline in lung function leading to respiratory failure. Respiratory failure, often preceded by a subacute deterioration (over weeks to months) or an acute deterioration (< 4 weeks), is the most common cause of death, but comorbid diseases such as lung cancer, infection, and heart failure are also common causes of death in these patients.17,18

Predictors of mortality include worsening FVC, DLCO, symptoms, and physiologic impairment, manifested by a decline in the 6-minute walking test or worsening exertional hypoxemia.19–22 Other common comorbidities linked with impaired quality of life and poor prognosis include obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and depression.16,23 Retrospective studies suggest that most IPF patients die 2 to 5 years after symptom onset. With the lag from symptom onset to final diagnosis, the average life expectancy is as little as 2 years from the time of diagnosis.9,18,24,25

Two staging systems have been developed to predict short-term and long-term mortality risk based on sex, age, and physiologic parameters.23,24 The GAP (gender, age, physiology) index provides an estimate of the risk of death for a cohort of patients: a score of 0 to 8 is calculated, and the score is then categorized as stage I, II, or III. Each stage is associated with 1-, 2-, and 3-year mortality rates, with stage III having the highest rates. The GAP calculator (www.acponline.org/journals/annals/extras/gap) provides an estimate of the risk of death for an individual patient. The application of these tools for the management of IPF is evolving; however, they may be helpful for counseling patients about disease prognosis.

CLUES TO DIAGNOSIS

Histologic patterns

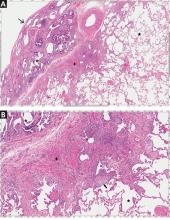

UIP on histologic study is also seen in fibrotic lung diseases other than IPF, including connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, inhalational or occupational interstitial lung disease, and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.26–29 Consequently, the diagnosis of IPF requires exclusion of other known causes of UIP.

According to the 2011 guidelines,16 the histology of interstitial lung disease can be categorized as definite UIP, probable UIP, or possible UIP, or as an atypical pattern suggesting another diagnosis. If no definite cause of the interstitial lung abnormality is found, the level of certainty of the histopathologic pattern of UIP helps formulate the clinical diagnosis and management plan.

Clues on computed tomography

The UIP nomenclature also describes patterns on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). HRCT is done without contrast and produces thin-sliced images (usually < 1.5 mm) in inspiratory, expiratory, and prone views; this allows detection of air trapping, which may indicate an airway-centric alternative diagnosis.

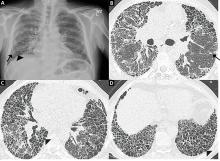

On HRCT, UIP appears as reticular opacities, often with traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis, usually with a basilar and peripheral predominance. Honeycombing is a key feature and appears as clustered cystic spaces with well-defined walls in the periphery of the lung parenchyma. Ground-glass opacities are not a prominent feature of UIP, and although they do not exclude a UIP pattern, they should spur consideration of other diagnoses.16 Reactive mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is another common feature of UIP.

When evaluating results of HRCT for UIP, the radiologist categorizes the pattern as definite UIP, possible UIP, or inconsistent. The definite pattern meets all the above features and has none of the features suggesting an alternative diagnosis (Figure 3). The possible pattern includes all the above features with the exception of honeycombing. If the predominant features on HRCT include any atypical finding listed above, then the study is considered inconsistent with UIP. If the pattern on HRCT is considered definite, evaluation of pathology is not necessary. If the pattern is categorized as possible or is inconsistent, then surgical lung biopsy-confirmed UIP is necessary for the definitive diagnosis of IPF.

However, evidence is emerging that in the correct clinical scenario, possible UIP behaves similarly to definite UIP and may be sufficient to make the clinical diagnosis of IPF even without surgical biopsy confirmation.30