Redefining treatment success in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Comprehensive targeting of core defects

ABSTRACT

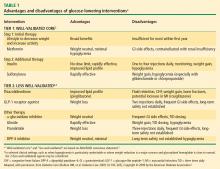

Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), overweight/obesity, cardiovascular disease, and their sequelae are major public health burdens worldwide. The understanding of the pathophysiology of T2DM has traditionally emphasized decreased insulin secretion and increased insulin resistance, but evolving concepts now include the role of incretin hormones in disease progression. A comprehensive approach to managing patients with T2DM requires targeting both the fundamental defects of the disease and its comorbidities, including the sequelae of nonoptimal control of blood glucose, blood pressure, body weight, and lipids. Newer antidiabetes agents, such as the glucagon-like peptide–1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and the dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, address fundamental defects related to glycemic control in T2DM and may have potential effects on other markers of cardiovascular risk. A redefinition of treatment success may be warranted as more data become available.

KEY POINTS

- The NHANES 1999–2004 data showed that only 13.2% of patients with diagnosed diabetes achieved concurrent weight, blood pressure, and lipid level goals.

- Among patients with T2DM, lifestyle intervention (control of weight, blood pressure, lipid levels) should be reinforced at every physician visit; glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should be monitored every 3 months until it is less than 7.0%, and then rechecked every 6 months.

- The effects of GLP-1 agonists on HbA1c are comparable to insulin analogues, but GLP-1 agonists are associated with weight reduction, while insulin is associated with weight gain.

- DPP-4 inhibitors have been associated with significant reductions in HbA1c when used alone or with metformin or pioglitazone.

BRIDGING THE GAP FROM PATHOPHYSIOLOGY TO UNMET NEEDS

The paradigm behind the pathophysiology of T2DM has shifted from its perception as a simple “dual-defect” disease (ie, deficiency in insulin secretion and peripheral tissue insulin resistance) to a multidimensional disorder.1,21 This new model includes overweight/obesity, insulin resistance, qualitative and quantitative defects in insulin secretion, and dysregulation in the secretion of other hormones, including the beta-cell hormone amylin, the alpha-cell hormone glucagon, and the gastrointestinal incretin hormones GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide.21–23

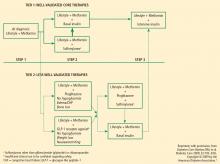

CLINICAL GUIDELINES AND CV RISK FACTOR MANAGEMENT

The best strategy for managing T2DM is a comprehensive approach that addresses the fundamental core defects plus associated factors that contribute to increased CV risk. Several specialty groups have suggested guidelines and algorithms for the management of T2DM and its comorbidities. These guidelines, including the ADA standards of medical care, the AACE standards in tandem with the American College of Endocrinology guidelines, and the recent joint statement from the ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), acknowledge that the core defects of T2DM and the associated CV risk factors (eg, weight gain, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia) are important in developing optimal treatment strategies.1–3 Medical nutrition guidelines advocate weight loss as a key initial step in managing T2DM and the comorbidities that lead to elevated CV risk.25,26 The National Institutes of Health and the US Department of Health and Human Services/US Department of Agriculture advocate regular physical activity, dietary assessment, and periodic comorbidity and weight assessment for all people, not just those with T2DM or CVD.26,27

Weight reduction

Evidence in support of effective lifestyle intervention was demonstrated in the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) study. After 1 year, patients with T2DM treated with intensive lifestyle intervention lost an average of 8.6% of their initial weight compared with 0.7% in patients treated only with diabetes support and education (P < 0.001). The intensive-intervention patients also had a significant drop in HbA1c (from 7.3% to 6.6%; P < 0.001) and were able to reduce their antidiabetes, antihypertensive, and lipid-lowering medications.28 More recent data from the Look AHEAD study reported that overweight patients with T2DM enrolled in a weight management program experienced significant weight loss, improved physical fitness, reduced physical symptoms, and overall improvement in health-related quality of life.29 Thus, weight reduction appears to be a key component in reducing CV risk and improving quality of life in most patients with T2DM.28–30

Hypertension

Hypertension is a major risk factor for microvascular complications and CVD, and may be associated with, or be the underlying result of, nephropathy.2 BP control is clearly important in reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with T2DM. The recommended BP goal in patients with T2DM is less than 130/80 mm Hg.1,2

Hyperlipidemia

According to the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III [ATP III]), diabetes is considered a CHD risk equivalent because it confers a high risk of new CHD developing within 10 years.31 In addition to the NCEP–ATP III guidelines, the ADA and the AACE have set target levels for lipids in patients with diabetes, including T2DM.1,2,31 All three organizations have defined 100 mg/dL as the target level for low-density lipoprotein.