Medicolegal issues in perioperative medicine: Lessons from real cases

ABSTRACT

Medical malpractice lawsuits are commonly brought against surgeons, anesthesiologists, and internists involved in perioperative care. They can be enormously expensive as well as damaging to a doctor’s career.

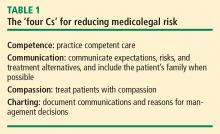

While physicians cannot eliminate the risk of lawsuits, they can help protect themselves by providing competent and compassionate care, practicing good communication with patients (and their families when possible), and documenting patient communications and justifications for any medical decisions that could be challenged.

KEY POINTS

- The standard to which a defendant in a malpractice suit is held is that of a “reasonable physician” dealing with a “reasonable patient.”

- In malpractice cases, the plaintiff need only establish that an allegation is “more likely than not” rather than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” threshold used for criminal cases.

- Plaintiffs typically seek damages (financial compensation) for economic losses as well as for pain and suffering. Awarding punitive damages against an individual physician for intentional misconduct is rare, and such damages are usually not covered by malpractice insurance.

- Settling a case is often cheaper and easier than going to court, but the physician’s reputation may be permanently damaged due to required reporting to the National Practitioner Data Bank.

- Informed consent should involve more than a patient signing a form: the doctor should take time to explain the risks of the intervention as well as available alternatives, and document that the patient understood.

REDUCING THE RISK OF BEING SUED

Regardless of the circumstances, communication is probably the most important factor determining whether a physician will be sued. Sometimes a doctor does everything right medically but gets sued because of lack of communication with the patient. Conversely, many of us know of veteran physicians who still practice medicine as they did 35 years ago but are never sued because they have a great rapport with their patients and their patients love them for it.

The importance of careful charting also cannot be overemphasized. In malpractice cases, experts for the plaintiff will comb through the medical records and be sure to notice if something is missing. The plaintiff also benefits enormously if, for instance, nurses documented that they paged the doctor many times over a 3-day period and got no response.

CASE 1: PATIENT DIES DURING PREOPERATIVE STRESS TEST FOR KNEE SURGERY

A 65-year-old man with New York Heart Association class III cardiac disease (marked limitation of physical activity) is scheduled for a total knee arthroplasty and is seen at the preoperative testing center. His past medical history includes coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and prior repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. He is referred for a preoperative stress test.

Dobutamine stress echocardiography is performed. His target heart rate is reached at 132 beats per minute with sporadic premature ventricular contractions. Toward the end of the test, he complains of shortness of breath and chest pain. The test is terminated, and the patient goes into ventricular tachycardia and then ventricular fibrillation. Despite resuscitative efforts, he dies.

Dr. Michota: From the family’s perspective, this patient had come for quality-of-life–enhancing surgery. They were looking forward to him getting a new knee so he could play golf again when he retired. The doctor convinced them that he needed a stress test first, which ends up killing him. Mr. Donnelly, as a lawyer, would you want to be the plaintiff’s attorney in this case?

Mr. Donnelly: Very much so. The family never contemplated that their loved one would die from this procedure. The first issue would be whether or not the possibility of complications or death from the stress test had been discussed with the patient or his family.

Consent must be truly ‘informed’ and documented

Dr. Michota: How many of our audience members who do preoperative assessments and refer patients for stress testing can recall a conversation with a patient that included the comment, “You may die from getting this test”? Before this case occurred, I never brought up this possibility, but I do now. This case illustrates how important expectations are.

Comment from the audience: I think you have to be careful of your own bias about risks. You might say to the patient, “There’s a risk that you’ll have an arrhythmia and die,” but if you also tell him, “I’ve never seen that happen during a stress test in my 10 years of practice,” you’ve biased the informed consent. The family can say, “Well, he basically told us that it wasn’t going to happen; he’d never seen a case of it.”

Dr. Michota: Are there certain things we shouldn’t say? Surely you should never promise somebody a good outcome by saying that certain rare events never happen.

Mr. Donnelly: That’s true. You can give percentages. You might say, “I’m letting you know there’s a possibility that you could die from this, but it’s a low percentage risk.” That way, you are informing the patient. This relates to the “reasonable physician” and “reasonable patient” standard. You are expected to do what is reasonable.

Is a signed consent form adequate defense?

Dr. Michota: What should the defense team do now? Let’s say informed consent was obtained and documented at the stress lab. The patient signed a form that listed death as a risk, but no family members were present. Is this an adequate defense?

Mr. Donnelly: It depends on whether the patient understood what was on the form and had the opportunity to ask questions.

Dr. Michota: So the form means nothing?

Mr. Donnelly: If he didn’t understand it, that is correct.

Dr. Michota: We thought he understood it. Can’t we just say, “Of course he understood it—he signed it.”

Mr. Donnelly: No. Keep in mind that most jurors have been patients at one time or another. There may be a perception that physicians are rushed or don’t have time to answer questions. Communication is really important here.

Dr. Michota: But surely there’s a physician on the jury who can help talk to the other jurors about how it really works.

Mr. Donnelly: No, a “jury of peers” is not a jury box of physicians. The plaintiff’s attorneys tend to exclude scientists and other educated professionals from the jury; they don’t want jurors who are accustomed to holding people to certain standards. They prefer young, impressionable people who wouldn’t think twice about awarding somebody $20 million.