Nuts and bolts of preoperative clinics: The view from three institutions

ABSTRACT

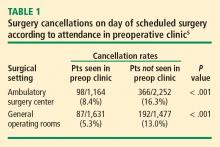

Three directors of dedicated preoperative assessment clinics share their experience in setting up and running their programs. Standardizing and centralizing all or part of the preoperative evaluation process—obtaining patient records; the history and physical examination; the surgical, anesthesiology, and nursing assessments; ordering tests; and documentation and billing—increases efficiency. The savings achieved from minimizing redundancy, avoiding surgery delays and cancellations, and improved reimbursement coding offset the increased costs of setting up and running the clinic.

KEY POINTS

- Standardizing the preoperative assessment process helps ensure that regulatory, accreditation, and payer requirements and guidelines are met.

- Careful triage based on a patient’s history can help avoid unnecessary assessment of low-risk patients and ensure that necessary assessments for higher-risk patients are completed before the day of surgery.

- Perioperative assessment and management guidelines for various types of surgery and patient risk factors should be developed, continuously updated, and made available online to all providers within the institution.

- Electronic medical records allow standardization of patient information, avoid redundancy, and provide a database for research.

CONSULTS HAVE AN IMPORTANT ROLE

Consults should never be requested in order to “clear a patient for surgery.” Consult requests should rather address specific issues, such as, “Is this patient medically optimized?” or “Please address this patient’s hypertension.” In turn, consult notes should provide meaningful information that can be used in a specific way. A clearance letter or simple risk assessment is not helpful.

If a patient has not seen a primary care doctor in a long time, a consult request should (in addition to requesting a global risk assessment) specify any particular concerns, such as, “The patient reports snoring; please address sleep apnea and cardiac risk.”

Case study: Beware consult notes with no specifics

Consider a case we encountered of a 54-year-old man who had a preoperative cardiac risk assessment. The cardiology consultant completed a short form consisting of a multiple-choice check-off list indicating low, moderate, or high cardiac risk. The consultant checked that the patient had low cardiac risk but provided no other instructions or information other than his own contact information.

When we reviewed the patient’s questionnaire, we saw that his medications included metoprolol, clopidogrel, and aspirin even though the patient did not mention that he had coronary artery disease. On this basis, we requested details about his cardiac evaluation from his cardiologist. It turned out that the patient had a history of four catheterizations with several cardiac stents placed. The most recent stent was implanted to overlap a previous stent that had been found “floating” in the blood vessel; this last stent was placed just 6 months before the cardiologist issued the consult note indicating “low cardiac risk.”

The moral is to approach consult notes with caution, especially if they offer no specifics. It actually makes me nervous when a note states “low risk” because if something unexpectedly goes wrong in surgery, it appears that the perioperative team took poor care of the patient even if the complication actually may have stemmed from higher-than-recognized underlying patient risk.

PROVIDE, AND REINFORCE, CLEAR INSTRUCTIONS

We give patients written preoperative instructions that become part of our computerized records. We first verbally give explicit instructions for each medication—ie, whether it can be taken as usual or when it needs to be stopped before surgery (and why). Then we provide the same information in writing, after which we try to have the patient repeat the instructions back to the clinician. We include a phone number that patients can call if they need help understanding their preoperative instructions.

Web-based programs also can provide patients online instructions about their medications. Some services even customize information by providing, for example, lists of local surgeons who are willing to allow a patient to continue on aspirin therapy until the day of surgery.

USE THE RIGHT RESOURCES

Staffing

Our model at the University of Chicago relies mainly on residents in training and physician assistants, but advanced nurse practitioners are well suited to a preoperative clinic as well. These types of providers have background training in history-taking, physical examination, diagnostic testing, and disease management. Registered nurses have more limited abilities, although they may be appropriate for a clinic that deals primarily with healthy patients for whom only history taking and a list of medications is needed. Additionally, our clinic is staffed by one attending anesthesiologist at all times (from among a group of rotating anesthesiologists) as well as medical assistants and clerical staff.

Some clinics perform the surgical history and physical exam at the same time as the anesthesia assessment. I would urge caution with this practice. Just as primary care doctors should not be conducting the anesthesia assessment, nonsurgeons should not be conducting the surgical assessment; doing so puts them out on a limb from a medicolegal standpoint. Advanced nurse practitioners and physician assistants may do surgical assessments under the supervision of a surgeon, but only surgeons should ultimately decide—and document—whether an operation is necessary and what degree of examination is required in advance.

Computer technology for records, messaging, billing

Using electronic medical records and corresponding with colleagues by e-mail make preoperative care much more efficient. We have standardized computer forms for ordering tests and documenting the physical exam. Patients usually understand that electronic medical records are safe and more efficient, and they are often more accepting of their use than practitioners are. Many patients want e-mail access to doctors, to schedule appointments online, and to receive appointment reminders by e-mail.3

Electronic medical records also avoid redundancy. If a patient has been seen in our preoperative clinic and is later scheduled for another surgery (even if a different surgeon is involved), a return visit to our clinic may not be necessary. In some cases, we can send the old work-up stamped “For information only,” which can then be updated by the anesthesiologist on the day of surgery.

A central, standardized process also makes billing more efficient and helps to ensure that payment is received for all services provided. Standardized documentation makes it easier for coders to enter the correct evaluation and management codes and ensures that all required criteria are met.

THE PAYOFF: LIVES AND DOLLARS SAVED

A thorough and efficient preoperative assessment system is cost-effective. Every minute of operating room time is worth $10 to $15,4,5 so delays should be avoided. Everything that is done ahead of time saves money for the whole enterprise by reducing unnecessary case setups and reducing “down time” due to lack of patient, equipment, or staff readiness. We routinely bill for preoperative evaluations when this service goes beyond a routine preoperative assessment based on CMS (and other insurance) requirements. However, a preoperative evaluation is required by CMS and most payers if one wants to be paid for any anesthesia-provided service. As a result, a cost is incurred without offsetting revenue if a case is cancelled on the day of surgery after one performs the anesthesia evaluation.

Yesterday I heard someone ask, “Do we really need all this preoperative evaluation? Does it really improve outcomes?” There is some evidence that it does. A study from 2000 based on data from the Australian Incident Monitoring Study found that 11% of the 6,271 critical incidents that occurred following operations were attributable to inadequate preoperative evaluation and that 3% were unequivocally related to problems with preoperative assessment or preparation. More than half of the incidents were deemed preventable.6

Preoperative clinics are good for patients and make good sense economically. We just need to demonstrate to our administrators and to payers that we are offering an excellent service.