Perioperative management of obstructive sleep apnea: Ready for prime time?

ABSTRACT

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease and stroke and with elevated rates of postoperative complications (including cardiac ischemia and respiratory failure) in surgical patients. Additionally, the prevalence of OSA is higher in surgical patients than in the general population. Screening for OSA prior to surgery is recommended to identify patients at risk for postoperative complications. The presence of moderate or severe OSA calls for modified strategies of perioperative anesthesia, pain management, and postoperative monitoring to reduce the chance of OSA-associated complications.

KEY POINTS

- OSA is more common than asthma in adults, affecting 4% and 2% of middle-aged men and women, respectively.

- OSA is associated with serious health consequences, including increased risks for accidents, stroke, hypertension, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, and postoperative complications.

- Screening tools consisting of only a few questions are available to quickly and effectively identify risk for OSA prior to surgery.

- For surgical patients deemed to be at high risk for OSA, and for whom surgery cannot be delayed for diagnostic tests and OSA treatment, the best course is to proceed with surgery but assume the patient has moderate to severe OSA.

- Use of regional anesthesia, close attention to airway management, vigilant postoperative monitoring of pulse oximetry, and minimal use of opioids are recommended for patients with OSA.

An association with postoperative complications

OSA also has been shown to increase postoperative complication rates, increase the need for intensive care intervention, and prolong hospital stays.

Representative evidence. One of the first studies to characterize the postoperative risks of OSA was conducted by Mayo Clinic researchers who retrospectively reviewed 4 years of data for 101 patients with OSA who had had hip or knee replacement surgery within 3 years before (n = 36) or any time after (n = 65) their OSA diagnosis.16 Outcomes were compared with those of 101 matched controls without OSA who underwent the same operations. Only half the patients with diagnosed OSA prior to their operation used continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy at home prior to hospitalization. Complications occurred among 39% of patients with OSA and among 18% of control patients (P = .001). Serious complications requiring intensive care unit transfer for cardiac ischemia or respiratory failure occurred in 24% of patients with OSA versus only 9% of controls (P = .004), and hospital stays were longer for patients with OSA compared with controls (P < .007). Most complications occurred during the first day after surgery, but a small number occurred as late as postoperative days 4 and 5.

In a separate study designed to evaluate OSA screening tools, postoperative complication rates were assessed in 211 patients who underwent polysomnography to determine the presence or absence of OSA prior to elective surgery.17 Patients undergoing various elective procedures were included, but none were undergoing cardiac or bariatric procedures. The overall rate of postoperative complications was more than twice as high among patients with OSA compared with those without OSA (27.4% vs 12.3%; P = .02). The most common complication was oxygen desaturation (ie, level ≤ 90%), which occurred among 20.6% of patients with OSA versus 9.2% of patients without OSA (P < .04). There were no deaths or serious complications.

Potential causes of complications. In the immediate postoperative period, OSA-associated complications may be attributable to lingering effects of sedatives, which can often lead to respiratory problems. Later in the postoperative course, so-called REM rebound is more likely to be implicated in complications. Patients often experience sleep deprivation in the hospital due to constant interruptions. Once a patient does sleep, the amount of REM sleep increases to compensate for this deprivation. The REM stage is when most apneas and hypopneas occur, so the risk of hypoxemia is greatest in the REM stage. As a result, respiratory and cardiovascular complications such as arrhythmias can increase.

OSA AND THE PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Risk factors for OSA

Additionally, certain aspects of perioperative management can increase the risk of OSA in the perioperative setting. For example, general anesthesia can mimic the effects of sleep on the airway, reducing muscle tone and potentially leading to pharyngeal collapse. Normal response to hypercapnia is also diminished under general anesthesia and while patients remain sedated postoperatively, which subdues normal protective arousal mechanisms. This does not pose a problem while the patient remains intubated but highlights the need for respiratory monitoring in the extubated patient who is recovering from the residual effects of sedation.

History and physical examination

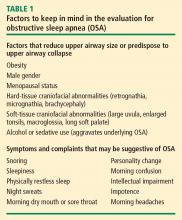

What to look for. A number of physical characteristics reveal potential risks for OSA. Obesity and hypertension are well established, as noted above. Large neck circumference (≥ 17 inches in men and ≥ 16 inches in women) is another characteristic associated with OSA. Examination of the upper airway can reveal obstruction due to tonsil enlargement, nasal obstruction, an elongated uvula, or macroglossia. Since retrognathia or micrognathia can produce a narrowed oropharynx, attention to mandible size and position is advised.

Ask about sleep habits. Assessment of OSA risk in the preoperative evaluation need not be lengthy, but patients should be asked about snoring and waking habits, especially frequency of night wakening, to identify possible OSA. Patients generally do not volunteer information about sleep, so it is important to explicitly ask. Responses that suggest OSA include reports of tiredness or sleepiness during the day, or comments by a partner about the patient’s snoring. A patient who reports having a dry mouth in the morning may have nasal congestion or obstruction that leads to mouth breathing. Severe sleep disruption can lead to sleep deprivation, causing personality changes, confusion, intellectual impairment, impotence, or morning headaches (Table 1).

Preoperative screening tools. Screening tools can assist in identifying relevant questions about sleep. Three such tools for OSA have been validated for use in surgical patients: the Berlin questionnaire, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) checklist, and the STOP questionnaire.17–20 The performance of these tools was evaluated in 177 surgical patients with OSA identified using polysomnography.17 Each tool’s sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated according to polysomnography-based AHI severity. All three tools demonstrated moderately high sensitivity for detecting OSA.17

Identifying levels of OSA severity. Physical examination and screening questions may be adequate to identify patients at risk for OSA prior to surgery. Mild OSA (AHI score of 5–15) can generally be managed after surgery, at the patient’s leisure. In contrast, moderate OSA (AHI score of 15–30) and severe OSA (AHI score > 30) can affect perioperative management (see next section). If moderate to severe OSA is suspected, and if there is enough time before surgery to consult a sleep lab, polysomnography can provide a more complete diagnosis.