Statins and noncardiac surgery: Current evidence and practical considerations

ABSTRACT

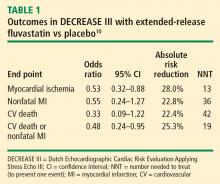

Vascular surgery is associated with a high risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality that is partly attributable to inflammatory stress induced by the surgical procedure. Preoperative initiation of a long-acting statin is a strategy intended to reduce the inflammatory stress response and the excess risk associated with vascular surgery. The Dutch Echocardiographic Cardiac Risk Evaluation Applying Stress Echo III demonstrated significant reductions in perioperative myocardial ischemia and the composite end point of myocardial infarction or cardiovascular death with extended-release fluvastatin (relative to placebo) initiated 30 days prior to vascular surgery. These benefits were achieved with no increase in liver dysfunction, evidence of myopathy, or other side effects. Observational data suggest that perioperative statin use is associated with improved recovery from acute kidney injury after high-risk vascular surgery and with improved long-term survival in patients undergoing such surgery.

KEY POINTS

- The inflammatory and oxidative stress induced by vascular surgery can be blunted by statin therapy.

- Statin therapy started preoperatively can reduce the incidence of myocardial ischemia and the level of inflammatory markers in patients undergoing high-risk vascular surgery.

- The purpose of perioperative statin use should be reduction of the inflammatory stress response to surgery, with the long-term goal being achievement of target lipid levels.

- A long-acting statin is preferred preoperatively to best extend the anti-inflammatory effects into the postoperative period. Statin therapy should be continued postoperatively, if possible, to avoid deleterious acute withdrawal effects.

Results: Favorable effect on clinical end points

The incidence of the primary end point—myocardial ischemia 30 days after surgery—was significantly lower in the patients randomized to extended-release fluvastatin compared with placebo (10.9% vs 18.9%; P = .016), as was the incidence of the secondary end point of cardiovascular death or nonfatal MI (4.8% vs 10.1%; P = .039).

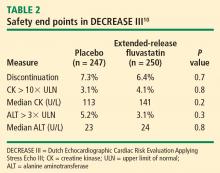

Safety: No effects on liver function or evidence of increased myopathy

We concluded that initiation of therapy with a long-acting statin should be considered in statin-naïve patients undergoing vascular surgery.

PERIOPERATIVE STATIN USE: PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Inflammation, not cholesterol, should be the target

The optimal statin choice and the target level of LDL cholesterol immediately prior to surgery remain controversial. It may be that the more potent statins induce more side effects during surgery, but any such claim is speculative since no comparative studies exist. Regardless, the purpose of perioperative statin use should be reduction of the inflammatory stress response to surgery, with the long-term goal being achievement of recommended target lipid levels.

In particular, patients with peripheral arterial disease should have a statin initiated prior to high-risk vascular surgery (if they are not already receiving one), to increase the odds of recovering renal function after surgery (see section below) and to improve long-term outcomes.

Who are the best candidates?

Patients with multiple cardiac risk factors represent an especially high-risk group that benefits the most from statin therapy prior to vascular surgery, as they are likely to have more extensive disease and more extensive inflammation in the coronary artery tree.

Given the low incidence of side effects associated with statins, initiating a statin in patients with multiple cardiac risk factors who are undergoing intermediate-risk surgery may seem appropriate, but no data from large randomized trials are available to support this practice. Caution is in order when extrapolating data from studies conducted in the high-risk vascular surgery context to other surgical settings, since statins may pose hidden side effects such as liver dysfunction and myopathy, which may be missed in patients under anesthesia.

My personal practice is to initiate a statin prior to high-risk surgery or in patients with multiple cardiac risk factors if the risk-factor profile presents a clear indication for long-term statin use. If no risk factors are present, I am more reluctant to initiate a statin because of a lack of supportive data.

Beware the rebound effect with statin withdrawal

Statin withdrawal for several days following surgery is a common practice, since statins are given orally and their pleiotropic effects are underappreciated.

A withdrawal effect leading to abrogation of clinical benefit has been observed with perioperative use of short-acting statins, whose anti-inflammatory properties do not effectively extend to the postoperative period. Acute withdrawal has been associated with an increase in markers of inflammation and oxidative stress, and an increase in cardiac events has been observed with acute withdrawal of statins during periods of instability when compared with continuation of statin therapy.11

For these reasons, a long-acting statin is preferred preoperatively in patients whose oral intake will be compromised for several days after surgery (eg, in gastric surgery). The optimal statin for preventing the withdrawal effect is unknown. We chose extended-release fluvastatin in DECREASE III because its biological effect appears to last at least 4 days12 even though analysis of serum levels of the drug indicates a shorter half-life.