The role of testing in the preoperative evaluation

ABSTRACT

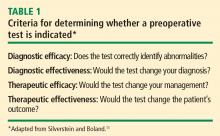

Preoperative laboratory and electrocardiographic testing should be driven by the patient’s history and physical examination and the risk of the surgical procedure. A test is likely to be indicated only if it can correctly identify abnormalities and will change the diagnosis, the management plan, or the patient’s outcome. Needless testing is expensive, may unnecessarily delay the operation, and puts the patient at risk for unnecessary interventions. Preoperative evaluation centers can help hospitals standardize and optimize preoperative testing while fostering more consistent regulatory documentation and appropriate coding for reimbursement.

KEY POINTS

- Age-based criteria for preoperative testing are controversial because test abnormalities are common in older people but are not as predictive of complications as information gained from the history and physical exam.

- Pregnancy testing is an example of an appropriate preoperative test because pregnancy is often not detectable by the history and physical exam and a positive result would affect case management.

- Routine ordering of preoperative electrocardiograms is not recommended because they are unlikely to offer predictive value beyond the history and physical exam and are costly to an institution over time.

- Routine and aged-based preoperative tests are no longer reimbursed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Should testing be based on age?

Using age as a criterion for preoperative testing is controversial. There is no doubt that the older a patient is, the more likely he or she is to have abnormal test results: patients aged 70 years or older have about a 10% chance of having abnormal levels of serum creatinine, hemoglobin, or glucose8 and a 75% chance of having at least one abnormality on their ECG (and a 50% chance of having a major ECG abnormality).9 However, these factors were found not to be predictive of postoperative complications. In contrast, predictive factors for this age group are an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification of at least 3 (indicating severe systemic disease), the risk of the surgical procedure, and a history of congestive heart failure.8,9

Guidelines for testing—and for not testing

About 10 years ago, the ASA attempted to develop a practice guideline for routine preoperative testing. The available data were so inconsistent, however, that the ASA could not reach a consensus and instead issued a practice advisory.10

Even so, there are a number of general principles for avoiding unnecessary preoperative testing:

- Routine laboratory tests are not good screening devices and should not be used to screen for disease

- Repetition should be avoided: there is no need to repeat a recent test

- Healthy patients may not need testing

- Patients undergoing minimally invasive procedures may not need testing

- A test should be ordered only if its results will influence management.

A CLOSER LOOK AT A FEW SPECIFIC TESTS

Question: Which of the following tests is most likely to provide useful information to aid clinical decision-making during a preoperative evaluation for laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

A. A chest radiograph in a 43-year-old woman with asthma

B. An ECG in a 71-year-old man with hypertension

C. A pregnancy test in an 18-year-old woman with amenorrhea

D. A prothrombin time in a 51-year-old man with anemia

E. A urinalysis in a 67-year-old woman with diabetes

The best answer is C (pregnancy test); an ECG in the 71-year-old man would be less useful (see below). The remaining choices—chest radiograph, prothrombin time, and urinalysis—are even less appropriate. A chest radiograph in an asthmatic patient is not likely to yield more information than what is obtained from the history and physical exam. Patients with anemia are not likely to have abnormal coagulation, and the role of urinalysis in detecting glucose and protein in asymptomatic diabetic patients is limited.

Routine pregnancy testing is justifiable

There are a number of reasons to justify a low threshold for preoperative pregnancy testing10:

- Patients, especially adolescents, are often unreliable in suspecting that they might be pregnant (in several studies of routine preoperative pregnancy screening, 0.3% to 2.2% of tests were positive)

- History and physical examination are often insufficient to determine early pregnancy

- Management usually changes if it is discovered that a patient is pregnant.

Using the four criteria from Table 1, pregnancy testing rates high as a useful test: it would identify “abnormality,” it would determine a diagnosis, and it would likely change management.

Routine ECG has limited utility

In contrast, routine preoperative ECG is not well supported. A recent study from the Netherlands assessed the added value of a preoperative ECG in predicting myocardial infarction and death following noncardiac surgery among 2,422 patients older than age 50 years.12 It showed that ECG findings were no more predictive of complications than findings from the history and physical examination and the patient’s activity level.

From our own data at Brigham and Women’s Hospital,13 we found that the presence of any of the following six risk factors predicted all but 0.44% of ECG abnormalities in patients aged 50 years or older presenting for preoperative evaluation:

- Age greater than 65 years

- Congestive heart failure

- High cholesterol

- Angina

- Myocardial infarction

- Severe valvular disease.

The 2007 guidelines on perioperative risk assessment from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) do not consider ECG to be indicated in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-risk noncardiac procedures regardless of patient age,14 like the 71-year-old man with hypertension in the above case question. These guidelines also state that evidence for routine ECG orders is not well established in patients with at least one clinical risk factor undergoing intermediate-risk procedures.

The aforementioned ASA practice advisory acknowledges that the likelihood of ECG abnormalities rises with increasing patient age, but the ASA was unable to reach consensus on a minimum age for routinely ordering an ECG in surgical candidates.10 The advisory recommends taking into account other factors, such as cardiac risk factors, the presence of cardiocirculatory or respiratory disease, and the type and invasiveness of the surgical procedure.10

In recommendations not specific to the perioperative setting, the US Preventive Services Task Force advises against routine screening for coronary heart disease with ECG or exercise treadmill testing.15 It gives routine screening a “D” recommendation, indicating that risk is greater than benefit because of the potential for unnecessary invasive procedures, overtreatment, and mislabeling of patients.

Our group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital recently surveyed anesthesiology program directors at US teaching hospitals to determine their preoperative test-ordering practices.16 Among the 75 respondents (58% response rate), 95% said their institutions have no requirements for ordering ECGs unless indicated based on age, history, or surgery type; 71% said their institutions have age-based requirements for ordering ECGs (usually > 50 years). Most respondents reported that their institutions are ordering fewer ECGs since the publication of the 2007 ACC/AHA guidelines on perioperative evaluation.

Whether or not age should be used as a criterion for ECG testing is controversial, and editorials on this subject abound.17–19 They point out that clinicians must be careful before abandoning routine ECGs in elderly patients, for several reasons:

- An abnormal ECG (or abnormal lab test results) may modify a patient’s ASA classification (which is predictive of complications)

- At least one-quarter of myocardial infarctions in elderly persons are “silent” or clinically unrecognized

- A preoperative ECG provides a useful baseline if the patient should develop ECG changes, chest pain, or cardiac complications during the perioperative period.

Most institutions use age as a criterion for ordering tests, especially for ECGs. If such a policy is used, a threshold of 60 years or older is probably most appropriate. However, a patient with good functional capacity who is undergoing a low-risk procedure does not need cardiac testing.14,20

An additional consideration is cost. Although the cost of a single ECG is modest, the cumulative cost of preoperative ECGs for all older surgical patients is significant over the course of a year. Because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) no longer cover routine preoperative ECGs, routine testing can be very costly to an institution over time.