The female athlete triad: It takes a team

ABSTRACT

The female athlete triad is a syndrome consisting of low energy availability (ie, burning more calories than one is taking in), menstrual dysfunction, and low bone mineral density, although all 3 components need not be present. Many providers, physical therapists, and coaches are unaware of it and thus do not screen for it. Early intervention using a team approach is essential in patients with any component of the female athlete triad to prevent long-term adverse health effects.

KEY POINTS

- Low energy availability is the driving force of the triad, causing menstrual irregularity and subsequent low bone mineral density.

- Recognizing that men as well as women can suffer from energy deficiency and that it can affect more than the female reproductive system and skeleton, the International Olympic Committee has proposed calling the disorder relative energy deficiency in sport.

- Screening for the triad with a specific set of questions is recommended during the preparticipation assessment.

- Early intervention and treatment prevents serious health consequences including life-threatening arrhythmias, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis.

DIAGNOSING THE TRIAD

Given that the signs of low energy availability and menstrual dysfunction are often subtle, the diagnosis of the triad for those at risk requires input from a multidisciplinary team including a physician, sports dietitian, mental health professional, exercise physiologist, and other medical consultants.

Table 2 lists diagnostic tests the primary care provider should consider.

Diagnosing low energy availability

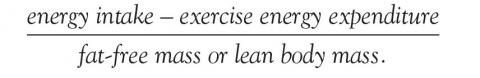

Energy availability is the dietary energy remaining after exercise energy expenditure; it is normalized to fat-free (lean) mass to account for resting energy expenditure. It is a product of energy intake, energy expenditure, and stored energy, and is calculated as:

An optimal value is at least 45 kcal/kg/day, while physiologic changes start to occur at less than 30 kcal/kg/day.4,31 Low energy is often seen in adult patients with a body mass index less than 17.5 kg/m2 and adolescent patients who are less than 80% of expected body weight.

Energy availability is hard to calculate, but certain assessments can be performed in a primary care setting to approximate it. To assess dietary intake, patients can bring in a 3-, 4-, or 7-day dietary log or complete a 24-hour food recall or food-frequency questionnaire in the office. To objectively document energy expenditure, patients can use heart rate monitors, accelerometers, an exercise diary, and web-based calculators. The fat-free mass can be calculated using a bioelectric impedance scale and skinfold caliper measurements.26

Those with chronic energy deficiency states may have reduced resting metabolic rates, with measured rates less than 90% of predicted and low triiodothyronine (T3) levels.31

Diagnosing menstrual dysfunction

When evaluating patients with menstrual dysfunction, it is important to first rule out pregnancy and endocrinopathies. These include thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia, primary ovarian insufficiency, other hypothalamic and pituitary disorders, and hyperandrogenic conditions such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, ovarian tumor, adrenal tumor, nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and Cushing syndrome.

Depending on the patient’s age, laboratory tests can include follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, serum estradiol, and a progesterone challenge.32 For hyperandrogenic symptoms, measuring total and free testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, 24-hour urine cortisol, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels may be helpful.

An endocrinologist should be consulted to evaluate the underlying cause of amenorrhea and address any associated hormonal imbalances. Attributing menstrual dysfunction to low energy availability is generally a diagnosis of exclusion. Additionally, outflow tract obstruction should be considered and ruled out with transvaginal ultrasonography in patients with primary amenorrhea.

A patient with hypoestrogenemia and amenorrhea may have the same steroid hormone profile as that of a menopausal woman. Lack of estrogen results in impaired endothelial cell function and arterial dilation, with accelerated development of atherosclerosis and subsequent cardiovascular events.33,34 Further, low energy availability has been linked to negative cardiovascular effects such as decreased vessel dilation leading to decreased tissue perfusion and hastened development of atherosclerosis.33 Female athletes with hypoestrogenism may show reduced perfusion of working muscle, impaired aerobic metabolism in skeletal muscle, elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and vaginal dryness.4

Diagnosing low bone mineral density

The most common clinical manifestations of low bone mineral density in female athletes are bone stress reactions such as stress fractures. In a study of 311 female high school athletes, 65.6% suffered from musculoskeletal injury from trauma or overuse including stress fractures and the patellofemoral syndrome.35 Many athletes seek medical attention from their primary care physician for stress reactions, providing an opportunity for triad screening.36

In postmenopausal women, osteopenia and osteoporosis are defined using the T score. However, in premenopausal women and adolescents, the International Society for Clinical Densitometry recommends using the Z score. A Z score less than –2.0 is described as “low bone density for chronological age.”14 For the diagnosis of osteoporosis in children and premenopausal women, the Society recommends using a Z score less than –2.0 along with the presence of a secondary risk factor for fracture such as undernutrition, hypogonadism, or a history of fracture.

Table 2 summarizes the diagnosis of low bone mineral density and osteoporosis in premenopausal women, adolescents, and children as well as when to order dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA).37,38

Adolescents with low bone mineral density should have an annual DEXA scan of the total hip and lumbar spine.22 Amenorrheic athletes typically present with low areal density at the lumbar spine, reduced trabecular volumetric bone mineral density and bone strength index at the distal radius, and deterioration of the distal tibia.39