Gallstones: Watch and wait, or intervene?

ABSTRACT

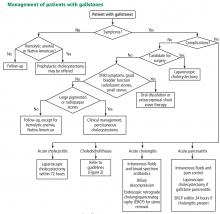

Gallstones are common in the United States, affecting an estimated 1 in 7 adults. Fortunately, they are asymptomatic in up to 80% of cases, and current guidelines do not recommend cholecystectomy unless they cause symptoms. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard treatment for symptomatic gallstones, acute cholecystitis, and gallstone pancreatitis.

KEY POINTS

- Abdominal pain is the primary symptom associated with gallstones.

- Abdominal ultrasonography is the diagnostic test of choice to detect gallstones and assess for findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis and dilation of the common bile duct.

- First-line therapy for asymptomatic gallstones is expectant management.

- First-line therapy for symptomatic gallstones is cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic gallstones

For patients experiencing acute cholecystitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 72 hours is recommended.48 There were safety concerns regarding higher rates of morbidity and conversion from laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy in patients who underwent surgery before the acute cholecystitis episode had settled. However, a large meta-analysis found no significant difference between early and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in bile duct injury or conversion rates.54 Further, early cholecystectomy—defined as within 1 week of symptom onset—has been found to reduce gallstone-related complications, shorten hospital stays, and lower costs.55–57 If the patient cannot undergo surgery, percutaneous cholecystotomy or novel endoscopic gallbladder drainage interventions can be used.

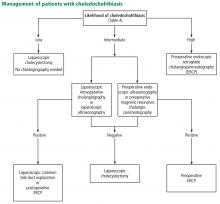

Several variables predict the presence of bile duct stones in patients who have symptoms (Table 4). Based on these predictors, the ASGE classifies the probabilities as low (< 10%), intermediate (10% to 50%), and high (> 50%)31:

- High-risk patients should undergo preoperative ERCP and stone extraction if needed

- Intermediate-risk patients should undergo preoperative imaging with EUS or MRCP or intraoperative bile duct evaluation, depending on the availability, costs, and local expertise.

Patients with associated cholangitis should be given intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Biliary decompression should be done as early as possible to decrease the risk of morbidity and mortality. For acute cholangitis, ERCP is the treatment of choice.25

Patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis should receive conservative management with intravenous isotonic solutions and pain control, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.48

The timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute gallstone pancreatitis has been debated. Studies conducted during the era of open cholecystectomy reported similar or worse outcomes if cholecystectomy was done sooner rather than later.

However, in 1999, Uhl et al58 reported that 48 of 77 patients admitted with acute gallstone pancreatitis were able to undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the same admission. Success rates were 85% (30 of 35 patients) in those with mild disease and 62% (8 of 13 patients) in those with severe disease. They concluded laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be safely performed within 7 days in patients with mild disease, whereas in severe disease at least 3 weeks should elapse because of the risk of infection.

In a randomized trial published in 2010, Aboulian et al59 reported that hospital length of stay (the primary end point) was shorter in 25 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy early (within 48 hours of admission) than in 25 patients who underwent surgery after abdominal pain had resolved and laboratory enzymes showed a normalizing trend, 3.5 vs 5.8 days (P = .0016). Rates of perioperative complications and need for conversion to open surgery were similar between the 2 groups.

If there is associated cholangitis, patients should also be given broad-spectrum antibiotics and should undergo ERCP within 24 hours of admission.25–27

SUMMARY

Gallstones are common in US adults. Abdominal ultrasonography is the diagnostic imaging test of choice to detect gallbladder stones and assess for findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis and dilation of the common bile duct. Fortunately, most gallstones are asymptomatic and can usually be managed expectantly. In patients who have symptoms or have gallstone complications, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the standard of care.