Management of hepatitis B in pregnancy: Weighing the options

ABSTRACT

Maternal screening and active and passive immunoprophylaxis have reduced the perinatal, or vertical, transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) dramatically. Without immunoprophylaxis, chronic HBV infection occurs in up to 90% of children by age 6 months if the mother is positive for both hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). Even with immunoprophylaxis, perinatal transmission is possible when the mother is highly viremic and HBeAg positive. Antiviral therapy during the third trimester of pregnancy in high-risk women with chronic HBV infection reduces viral load in the mother and may decrease the risk of perinatal transmission, although data are lacking. Safety data in pregnancy are most robust with lamivudine and tenofovir compared with other therapies. Careful discussion with the patient regarding the risks and benefits of therapy is warranted. Prophylaxis remains the best method of prevention of perinatal transmission.

KEY POINTS

- Hepatitis B immune globulin at the time of birth plus three doses of the recombinant hepatitis B vaccine over the first 6 months of life is up to 95% effective in

preventing perinatal transmission. - Despite successful screening and vaccination, perinatal transmission of HBV is still possible if maternal viral load is high.

- Antiviral treatment during the third trimester of pregnancy may reduce perinatal transmission of HBV; the benefit appears most pronounced with high maternal viremia.

TREATMENT DURING PREGNANCY

The use of active and passive immunoprophylaxis to reduce the risk of perinatal transmission of HBV is well accepted in clinical practice. HBIg given at the time of birth in combination with three doses of the recombinant hepatitis B vaccine given over the first 6 months of life has been up to 95% effective in preventing perinatal transmission. As noted above, however, the risk of perinatal transmission of HBV increases as the mother’s viral load increases. In one series of mothers with high viral loads, this risk was as high as 28%.15

It stands to reason that if the mother’s viral load can be reduced at the time of birth, the risk of perinatal transmission could also be reduced (see “Case: Minimizing risk in a 29-year-old woman”). In fact, lamivudine treatment of highly viremic HBsAg-positive women during the final months of pregnancy appears safe and may effectively reduce the risk of perinatal transmission of HBV, even in the setting of HBV vaccination plus HBIg.

Evidence for third-trimester treatment

van Zonneveld et al15 studied eight HBeAg-positive women with HBV DNA levels of 1.2 X 109 copies/mL or greater who were treated with 150 mg/day of lamivudine after the 34th week of pregnancy, and compared the rates of perinatal transmission between them and 24 matched historical controls who did not receive treatment. All children received standard immunoprophylaxis at birth and were followed for 12 months. In five of the eight treated mothers, viral load declined to less than 1.2 X 108 copies/mL. Of the eight infants born to treated mothers, four were HBsAg positive at birth, but only one remained positive at 1 year. This 12.5% rate of perinatal transmission was substantially lower than the 28% rate observed among the controls. No adverse events occurred with lamivudine in this study.

In a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in China and the Philippines, Xu et al16 assessed outcomes among 114 HBsAg-positive pregnant women who had high viral loads (HBV DNA > 1,000 mEq/mL). The women were randomized to placebo or treatment with lamivudine starting at 32 weeks of gestation and continuing until 4 weeks postpartum. All of the infants received standard vaccine plus HBIg.

The mothers treated with lamivudine were more likely (98%) to have a reduction in their viral loads to less than 1,000 mEq/mL than the controls (31%). This reduction in viral load translated to improved outcomes for the infants of mothers receiving lamivudine. At 1 year, 18% of infants born to mothers treated with lamivudine were HBsAg positive compared with 39% of infants born to mothers randomized to placebo (P = .014). The rate of HBV DNA positivity at 1 year was reduced by more than half among the infants born to actively treated mothers compared with those who received placebo (20% vs 46%, respectively; P = .003). There was no difference in the rate of adverse events between the treatment and control groups in either the mothers or the infants.

The Xu study suggests that the use of lamivudine in the third trimester in mothers with high viral loads may effectively reduce the risk of perinatal transmission beyond what can be achieved with active and passive immunoprophylaxis. As this study has been presented in abstract form only, we await the final analysis of these data. This therapy appears to be relatively safe for both mother and infant, although the optimal timing and duration of therapy is still unclear.

Treatment options during pregnancy

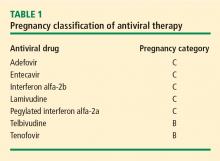

Most human experience with antiviral drug therapy in pregnancy has been with lamivudine. More than 4,600 women have been exposed to the drug during their second or third trimesters.17 Even though lamivudine is classified as FDA pregnancy risk category C, it is associated with a risk of birth defects (2.2% to 2.4%) that is no higher than the baseline birth defect rate.17

Of the two agents classified as FDA pregnancy risk category B, only tenofovir received this classification based on data collected in human exposure. The experience with tenofovir in pregnant women consists of 606 women in their first trimester and 336 in their second trimester.17 The rate of birth defects associated with tenofovir ranges from 1.5% (second-trimester use) to 2.3% (first-trimester use), which is similar to the background rate.17 Telbivudine received its pregnancy risk category B rating based on animal studies; there are few human pregnancy registry data.

Nonpegylated interferon alfa-2b has been shown to have abortifacient effects in rhesus monkeys at 15 and 30 million IU/kg (estimated human equivalent of 5 and 10 million IU/kg, based on body surface area adjustment for a 60-kg adult). Peginterferon alfa-2b should therefore be assumed to also have abortifacient potential, as there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. Peginterferon alfa-2b is to be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. It is recommended for use in fertile women only when they are using effective contraception during the treatment period. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a is approved for treatment of chronic HBV infection, but is not recommended for use during pregnancy.