Dyspnea and Hyperinflation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Impact on Physical Activity

Introduction

Dyspnea, the sensation of difficult or labored breathing, is the most common symptom in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the primary symptom that limits physical activity in more advanced disease.1 According to the American Thoracic Society, dyspnea may be measured according to 3 domains2:

- what breathing feels like for the patient

- how distressed the patient feels when breathing

- how dyspnea affects functional ability, employment, health-related quality of life, or health status.

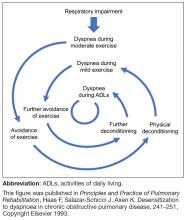

As disease severity increases, breathlessness becomes more disabling at lower activity levels. These changes further impact the quality of life of patients, and can lead to anxiety and depression.11

Physical inactivity is often considered to be a major contributor to the progression of COPD,6 and is linked to hospitalizations and increased all-cause mortality.12 There is therefore a need to recognize symptoms early and treat them accordingly.

CASE STUDY:

KD, a 64-year-old woman, presented to her primary care physician’s office for a routine visit. Upon assessment, KD revealed that she used to enjoy going on walks with her neighbor, but she cannot walk up the hills in her neighborhood anymore without feeling “incredibly breathless.” She has become increasingly concerned that she is “having trouble getting a full breath.” KD informed her doctor that these symptoms had worsened since her last visit, and so she had stopped going on neighborhood walks. She was diagnosed with COPD 4 years ago, and is currently using a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) bronchodilator. KD has a 40 pack-year smoking history, and has previously been advised to stop smoking, but has relapsed several times. She has a medical history of hypertension and depression, and a notable family history of emphysema, breast cancer, and diabetes.

The relationship between lung hyperinflation and dyspnea in COPD

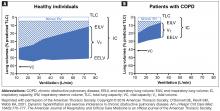

In COPD, pathologic changes give rise to physiologic abnormalities such as mucus hypersecretion and ciliary dysfunction, gas exchange abnormalities, pulmonary hypertension, and airflow limitation and lung hyperinflation.13 Lung hyperinflation, an increase in resting functional residual volume above a normal level, represents a mechanical link between the characteristic expiratory airflow impairment, dyspnea, and physical activity limitation in COPD.1

Although patients can compensate for several of the negative consequences of hyperinflation (eg, altering the chest wall due to overdistended lungs), such compensatory mechanisms are unable to cope with large increases in ventilation, such as those that occur during exercise.1 Air trapping, together with ineffectiveness of respiratory muscle function, leads to increased ventilation requirements and dynamic pulmonary hyperinflation, resulting in dyspnea.1

Patients with COPD describe a sensation of “air hunger,” reporting “unsatisfied” or “unrewarded” inhalation, “shallow breathing,” and a feeling that they “cannot get a deep breath,”18 whereas, in fact, they are limited in their ability to fully exhale. Verbal descriptors (eg, “air hunger” or “chest tightness”) are important tools in understanding a patient’s experience with dyspnea, and a patient’s choice of descriptor may be related to dyspnea severity, and the level of distress that dyspnea causes a given patient.19 Air hunger in turn encourages faster breathing, leading to further shortness of breath and more dynamic hyperinflation.1,20

To deflate the lungs of patients with COPD, physiologic, pharmacologic, and possibly surgical interventions are required:

- Controlled breathing techniques (eg, purse-lipped breathing) that encourage slow and deep breathing can correct abnormal chest wall motion, decrease the work of breathing, increase breathing efficiency, and improve the distribution of ventilation to empty the lungs.21

- Bronchodilators can help to achieve lung deflation by improving ventilatory mechanics, as shown by increases in inspiratory capacity and vital capacity.22

- Lung volume reduction surgery can also be considered to treat severe hyperinflation in emphysematous patients5; bronchoscopic interventions that lower lung volumes are also in development.23

The impact of lung hyperinflation and dyspnea on physical activity in COPD

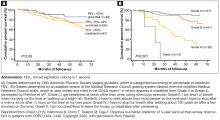

Dyspnea and hyperinflation are closely interrelated with physical activity limitation,16,29,30 and so can be viewed as significant contributors to patient disability. During an acute exacerbation, patients with COPD will experience worsening airway obstruction, dynamic hyperinflation, and dyspnea.31 Patients with a greater number of comorbid conditions may also have greater shortness of breath.32 In addition, patients with COPD and hyperinflation perform less physical activity than individuals without hyperinflation, regardless of COPD severity, as assessed using the 2007 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) staging (stage I, mild; stage II, moderate; stage III, severe; stage IV, very severe) and BODE (Body-mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise) index.33 These patients also exhibit increases in dyspnea perception during commonly performed ADLs, which may limit physical activity and worsen lung hyperinflation.33 More limited physical activity also contributes to higher dyspnea scores during ADLs.8

Furthermore, the ability to perform typical ADLs may be significantly altered or eliminated altogether in patients with COPD.11 Leisure activities are often the first to be dropped by patients, as they generally require greater effort than simpler tasks, and are not critical to daily life.11 Eventually, these activities become progressively more difficult, and most patients with moderate or severe COPD can struggle to complete even the most basic daily activities.11

In addition to the morbidity burden and impact on ADLs, lower levels of physical activity in patients with COPD have also been shown to increase the risk of mortality and exacerbations, and elevate the risk of comorbidities such as heart disease and metabolic disease.34 In light of these observations, improving exercise capacity should be a key goal in COPD management.

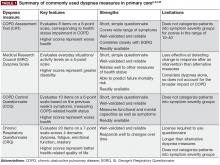

Assessment and measurement of dyspnea and hyperinflation

Reducing hyperinflation and dyspnea is essential for improving physical activity endurance and overall physical activity in patients with COPD; therefore, measuring the degree of impairment is important.22 Clinicians should be aware that some patients may have relief of dyspnea due to improvements in hyperinflation, despite relatively mild changes in FEV1.35 Lung volume measures, including total lung capacity, residual volume and functional residual capacity, are valuable tools in the assessment of lung hyperinflation in COPD, and therefore constitute a key component of pulmonary function testing.36 However, expanded pulmonary function testing may be required for patients with severe dyspnea that does not correspond to spirometric findings, or cases in which diagnosis is uncertain.37

Lung volumes are evaluated primarily by body plethysmography, during which a patient sits inside an airtight “body box” equipped to measure pressure and volume changes.14,38 Helium dilution and nitrogen washing can also be used to measure functional residual capacity in patients with COPD,14 but body plethysmography is considered to be a more accurate method of lung volume evaluation in patients with severe airflow obstruction.14,38 Radiographic techniques can also be used, but due to a lack of standardization, they are not typically utilized in clinical practice.14 Measurement of IC may complement other lung volume measures as part of assessment of hyperinflation.16 This can be measured using either spirometry or body plethysmography.39,40

In addition to evaluating hyperinflation, ADLs, physical activity, exercise capacity, and dyspnea should all be assessed in patients with COPD in primary care. It is known that patients may self-limit ADLs to avoid symptoms of COPD; in doing so, worsening symptoms may be underappreciated, and subsequently underreported, by the patient. Thus, it is essential that physicians ask patients with COPD, as well as individuals at risk of COPD, questions about changes in their physical activity or ability to perform common tasks. There are a number of methods to measure functional performance, but for a simple assessment of ADLs, clinicians can ask the patient or caregiver questions related to basic daily tasks.11 In early COPD, patients who experience mild dyspnea during exercise should be able to perform most productive activities. Patients with stable COPD and moderate dyspnea during exercise should be able to carry out most of the higher functioning ADLs, whereas patients with severe COPD may struggle to complete basic ADLs without assistance.11 It should be noted, however, that patients may experience dyspnea with fairly routine activities, and even reduce physical activity at relatively early stages of airflow limitation.41,42

Other tests may be useful in assessing the impact of an intervention, be it pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic, on dyspnea severity. For example, increases in the 6-minute-walk distance (6MWD) have been shown to correlate with improvements in dyspnea.46 The 6MWD has also been shown to be an important predictor of hospitalization and mortality in patients with COPD.47 However, it is important to note that improvements in 6MWD show only a very weak correlation with patient-reported outcomes,48 and may be a less sensitive measure for patients with less disability than those with more profound functional limitation.49 Moreover, 6MWD can be affected by a patient’s psychologic motivation,6,50 as well as other comorbidities observed in patients with COPD, such as osteoporosis, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease.46,51 Although not used for COPD diagnosis or evaluation of dyspnea or physical activity limitation, a chest X-ray can also be a useful tool for excluding alternative diagnoses, as well as for detecting significant comorbidities in patients with COPD, such as concomitant respiratory, cardiac, and skeletal diseases.5