Medication management in older adults

ABSTRACT

Managing medications is a major part of providing care to older adults. Polypharmacy is common in the elderly and is fraught with risks. A careful and systematic approach is needed for managing drug therapy in these patients, recognizing the patient’s specific goals.

KEY POINTS

- Statins, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and proton pump inhibitors are widely prescribed.

- In older patients, a periodic comprehensive medication review is needed to reevaluate the risks and the benefits of current medications in light of goals of care, life expectancy, and the patient’s preferences.

- The Beers criteria and the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions provide valuable guidance for safe prescribing in older adults.

Benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are among the most commonly prescribed psychotropics in developed countries and are prescribed mainly by primary care physicians rather than psychiatrists.23

In 2008, 5.2% of US adults ages 18 to 80 used a benzodiazepine, and long-term use was more prevalent in older patients (ages 65–80).23

Benzodiazepines are prescribed for anxiety,24 insomnia,25 and agitation. They can cause withdrawal26 and have potential for abuse.27 Benzodiazepines are associated with cognitive decline,28 impaired driving,29 falls,30 and hip fractures31 in older adults.

In addition, use of nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics (eg, zolpidem) is on the rise,32 and these drugs are known to increase the risk of hip fracture in nursing home residents.33

The American Geriatrics Society, through the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign, recommends avoiding benzodiazepines as a first-line treatment for insomnia, agitation, or delirium in older adults.34 Yet prescribing practices with these drugs in primary care settings conflict with guidelines, partly due to lack of training in constructive strategies regarding appropriate use of benzodiazepines.35 Educating patients on the risks and benefits of benzodiazepine treatment, especially long-term use, has been shown to reduce the rate of benzodiazepine-associated secondary events.36

Antipsychotics

Off-label use of antipsychotics is common and is increasing in the United States. In 2008, off-label use of antipsychotic drugs accounted for an estimated $6 billion.37 A common off-label use is to manage behavioral symptoms of dementia, despite a black-box warning about an increased risk of death in patients with dementia who are treated with antipsychotics.38,39 The Choosing Wisely campaign recommends against prescribing antipsychotics as a first-line treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.34

Antipsychotic drugs are associated with risk of acute kidney injury,40 as well as increased risk of falls and fractures (eg, a 52% higher risk of a serious fall, and a 50% higher risk of a nonvertebral osteoporotic fracture).41

Patients with dementia often exhibit aggression, resistance to care, and other challenging or disruptive behaviors. In such instances, antipsychotic drugs are often prescribed, but they provide limited and inconsistent benefits, while causing oversedation and worsening of cognitive function and increasing the likelihood of falling, stroke, and death.38,39,41

Because pharmacologic treatments for dementia are only modestly effective, have notable risks, and do not treat some of the behaviors that family members and caregivers find most distressing, nonpharmacologic measures are recommended as first-line treatment.42 These include caregiver education and support, training in problem-solving, and targeted therapy directed at the underlying causes of specific behaviors (eg, implementing nighttime routines to address sleep disturbances).42 Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia can significantly improve quality of life for patients and caregivers.42 Use of antipsychotic drugs in patients with dementia should be limited to cases in which nonpharmacologic measures have failed and patients pose an imminent threat to themselves or others.43

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the United States, and their use has increased significantly over the decade. It has been estimated that between 25% and 70% of these prescriptions have no appropriate indication.44

There is considerable excess use of acid suppressants in both inpatient and outpatient settings.45,46 In one study, at discharge from an internal medicine service, almost half of patients were taking a proton pump inhibitor.47

Evidence-based guidelines recommend these drugs to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease, nonerosive reflux disease, erosive esophagitis, dyspepsia, and peptic ulcer disease. However, long-term use (ie, beyond 8 weeks) is recommended only for patients with erosive esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, a pathologic hypersecretory condition, or a demonstrated need for maintenance treatment for reflux disease.48

Although proton pump inhibitors are highly effective and have low toxicity, there are reports of an association with Clostridium difficile infection,49 community-acquired pneumonia,50 hip fracture,51 vitamin B12 deficiency,52 atrophic gastritis,53 kidney disease,54 and dementia.55

Nondrug therapies such as weight loss and elevation of the head of the bed may improve esophageal pH levels and reflux symptoms.56

Deprescribing.org has practical advice for healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers on how to discontinue proton pump inhibitors, including videos, algorithms, and guidelines.

TOOLS TO EVALUATE APPROPRIATE DRUG THERAPY

Beers criteria

The Beers criteria (Table 2), developed in 1991 by a geriatrician as an approach to safer, more effective drug therapy in frail elderly nursing home patients,57 were updated by the American Geriatrics Society in 2015 for use in any clinical setting.58 (The criteria are also available as a smartphone application through the American Geriatrics Society at www.americangeriatrics.org.)

The Beers criteria offer evidence-based recommendations on drugs to avoid in the elderly, along with the rationale for use, the quality of evidence behind the recommendation, and the graded strength of the recommendation. The Beers criteria should be viewed through the lens of clinical judgment to offer safer nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments.

The Joint Commission recommends medication reconciliation at every transition of care.59 The Beers criteria are a good starting point for a comprehensive medication review.

STOPP/START criteria

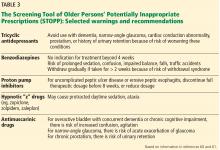

Another tool to aid safe prescribing in older adults is the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP), used in conjuction with the Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to Right Treatment (START). The STOPP/START criteria60,61 are based on an up-to-date literature review and consensus (Table 3).

THE BOTTOM LINE

Physicians caring for older adults need to diligently weigh the benefits of drug therapy and consider the patient’s care goals, current level of functioning, life expectancy, values, and preferences. Statin therapy for primary prevention, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and proton pump inhibitors are widely used without proper indications, pointing to the need for a periodic comprehensive review of medications to reevaluate the risks vs the benefits of the patient’s medications. The Beers criteria and the STOPP/ START criteria can be useful tools for this purpose.